1. INTRODUCTION

Since the existence of human civilization, plants have been the most exploited and utilized natural sources for survival (Chaachouay & Zidane, 2024). From daily consumable food to treating several diseases, different parts of plants have crucial roles. The study of indigenous use of plants to treat ailments is called ethno-pharmacognosy. Fruits are one of those plant parts which are used extensively for thriving daily lives (Nasim et al., 2022). Most of the ripe fruits can be consumed either cooked or uncooked, but unripe fruits are also potentially capable of being consumed. These unripe fruits are consumed traditionally not only as a food but also because of their potential health benefits (Rahman, Dhar, et al., 2022).

In recent times the interest of the pharmaceutical industry has shifted from chemically synthesized products to naturally obtained products which are synthesized chemically. This is because of the lesser toxicity of the naturally obtained compounds (Nasim et al., 2022). The shift to natural products has increased the interest in the knowledge of ethnobotany and traditional medicine. Unripe fruits are recognized for their potential nutritional and therapeutic values. Unripe fruits are greatly targeted because of their rich reservoir of bioactive compounds and because they provide unique opportunities for drug discovery and development (Atanasov et al., 2015; Joshi et al., 2016).

Green papaya is used in the cuisine of South East Asia. It has a high level of papain enzyme, a protease enzyme, that is supposed to promote digestive health (Nafiu & Rahman, 2015; S. P. Singh et al., 2020). Green breadfruit is often consumed by Pacific Islanders which apart from boosting digestion has a potential of managing diabetes and an ability to boost cardiovascular health (Soifoini et al., 2021; Thomas et al., 2022). Green unripe mangoes are often consumed in the Indian subcontinent because its high vitamin C content can treat scurvy (Lebaka et al., 2021). Unripe bael fruits are traditionally used to treat diarrhea and dysentery while young green mulberries are shown to support liver health (Monika et al., 2023). Similarly, green guava, rich in vitamin C and tannins, reduces dental problems and digestive ailments (Lok et al., 2023). Unripe green bananas are extensively consumed in the Indian subcontinent. These green bananas are rich in resistant starch and have been traditionally used to support gut health because of their probiotic features and also to regulate blood sugar levels (Falcomer et al., 2019; Menezes et al., 2011).

Fruits during their maturation process undergo diverse changes in their chemical and phytoconstituent profiling including changes in alkaloids, glycosides, tannins, polyphenols, and other components. These secondary metabolites are synthesized by the plants for their defense against the environmental predators (Wink, 2015). These same compounds, which might render the unripe fruit less palatable, could possess significant pharmacological potential (Erb & Kliebenstein, 2020).

The need to develop a more specific therapeutic agent with lesser side effects and more potency than the conventional pharmaceutical agents have emerged. Exploration of these unripe fruits to find out its constituent can overcome potential health challenges including increasing antibiotic resistance and inclination to development of chronic diseases (Sruthi et al., 2023). This review article encompasses several findings of different literature about traditional importance, folklore, and ethnopharmacological importance of five different unripe fruits to correlate the traditional knowledge of the health benefits to the modern pharmacological uses (Nasim et al., 2022). Hence, this opens new opportunities to pharmaceutical industries for potential drug development from the therapeutically important compounds.

2. POTENTIAL HEALTH BENEFITS OF UNRIPE FRUITS

Unripe fruits contain unique phytoconstituents and bioactive phytoconstituents which are quite different from their ripe counterparts. Most unripe fruits have the potential capability of lowering glycemic index compared to their ripe portions. The dietary fiber contributed by the unripe fruits is generally higher contributing to better digestive health and promoting digestion (Dhingra et al., 2012).

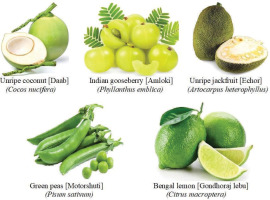

The unripe fruits selected for this work which can have well-defined prospects for further investigation in the pharmaceutical field are unripe coconut, green Indian gooseberry, unripe jackfruit, green peas, and Bengal lemon. The pictorial representation of these unripe fruits is given in Figure 1.

Table 1 defines the traditional health benefits and the habitat of growth of these fruits.

Table 1

Health benefits and ethnomedicinal uses of some unripe fruits.

| Sl. No. | Common name (Scientific name); Family | Habitat of growth | Traditional/Ethnomedicinal uses | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Unripe coconut/ Daab (Cocos nucifera(L.)); Arecaceae | Tropical coastal land and saline, sandy, and loamy soil; Plenty rainfall and sunlight; Temperature > 12oC and rainfall > 1500–2500mm. | Hydration of body; used as natural oral rehydration salt; energy rejuvenating solution; contains plenty of nutrients; treats gastrointestinal disorder; boosts immunity; treats urinary infection; reduces body heat; helps to withstand summer heat. | (Devi & Ghatani, 2022; Mat et al., 2022) |

| 2. | Indian gooseberry/Amlaki/Amla (Phyllanthus emblica); Phyllanthaceae | Generally wild domestic plant cultivated in the Indian subcontinent; Grows at 0–2000 m altitude; and diverse conditions of soil. | Treatment of cold and cough, sore throat; relief from respiratory infection; Decoctions used to strengthen hair follicle; supports digestion, reduces and manages motion sickness and vomiting-like symptoms, digestive aid, boosting immunity. Ayurveda mentions amla as a rejuvenating agent; treats diabetes and cardiac diseases, reduces lipid levels | (Gul et al., 2022; V.Kumar et al., 2017; Saini et al., 2022) |

| 3. | Unripe jackfruit/ Echor (Artocarpus heterophyllus); Moraceae | Generally, grows in tropical region and is common in Bengal and Bangladesh. Well-drained, rich alluvial soil; at optimal temperature 22–32°Cwith high humidity and rainfall. Jackfruit is the largest fruit ranging up to even 55 kg. | Because of the unique texture, raw jackfruit is often considered as a meat substitute. Prevents inflammations, intestinal ulcer, and hence prevents bloating and indigestion; manages diarrhea, prevents symptoms of polyuria or diabetes mellitus; has wound-healing property and anti-microbial activity | (Gupta et al., 2023; Nantongo et al., 2022; Tripathi et al., 2023) |

| 4. | Green peas/ Motorshuti (Pisum sativum); Fabaceae | Generally, grows in cooler or winter months when temperature is less than 16oC; suits in well-drained loamy soil; requires less to moderate rainfall; grows well at higher elevation and higher altitude; matures within 2 months of planting. | Highly nutritious and boosts the immune system; reduces the risk of cardiovascular diseases and lowers cholesterol levels; rich in fiber and boosts digestion; traditionally used as blood purifier and blood thinner; thus, reduces blood cholesterol and blood pressure levels. Green peas are a good source of protein and helps to manage diabetes. Treats inflammation and reduce the signs of ulceration. | (Guo et al., 2021; Shanthakumar et al., 2022; Wu et al., 2023) |

| 5. | Bengal lemon/ Gondhoraj lebu (Citrus limon); Rutaceae | Native to the Indian subcontinent and specially in West Bengal. Generally, it grows in well-drained soil with plenty of water supply in tropical climate with average temperature of 25–30oCand moderate to high rainfall. Requires direct exposure to sunlight. | Used because of its extremely rich flavor and aroma; citrus in nature and hence treats cough and cold, sore throat, and respiratory ailments; used to prevent signs and symptoms of nausea, vomiting, and motion sickness. | (Makni et al., 2018; Posadino et al., 2024; N.Singh et al., 2021) |

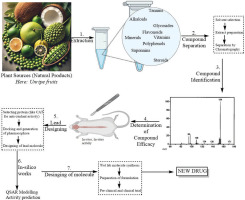

3. RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BIOACTIVE COMPOUNDS AND DRUG DISCOVERY

Chemical compounds found in plant parts are classified into two categories: Primary and secondary metabolites. Primary metabolites like carbohydrates, protein, and lipids are required for normal functioning of the plant. Secondary metabolites are excretory substances that are produced for the defense mechanism of the plant. These secondary metabolites include phytoconstituents like alkaloids, saponins, tannins, flavonoids, etc. It has been found that these secondary metabolites interact with different receptors, proteins, and nucleic acids of the human body and hence show biological effect. Since these secondary metabolites elicit the pharmacological effects, they are called bioactive substances (Guerriero et al., 2018; L. Yang et al., 2018).

These bioactive compounds or secondary metabolites are primarily focused by the pharmaceutical industry for the development of new drugs and synthesizing these natural products chemically. This tedious and long step when cut short includes steps like (Erb & Kliebenstein, 2020; Seca & Pinto, 2019; Yeshi et al., 2022):

Preparing extracts of the plant species (unripe fruits with special interest).

Separating the components by analytical techniques like HPTLC, HPLC, and GC.

Identification of the structural features of the separated compounds by NMR or LC-MS and GC-MS.

Identifying which chemical compound shows biological activity in the human body.

Predicting the biological activity of each compound followed by lead design and developing a new drug molecule by different in-silico techniques (pharmacophore design, docking, lead design, and others).

This follows synthesis of the new novel drug moiety which is called semi-synthetic drug moiety.

This semi-synthetic drug candidate undergoes preclinical and clinical trial, pharmacokinetics study to become a new successful drug moiety

Since the naturally obtained bioactive compounds can be synthesized in the laboratory for further use, or they can be structurally modified to increase the specificity and the potency and the semi-synthetic novel drug can be used further for lead design, plant parts have gained enormous importance in today’s world (Yeshi et al., 2022).

The fruits are formed to form future progeny for the plants. To conserve and defend these unripe fruits from predators and other environmental pathogens, plants secrete and synthesize more secondary metabolites. Hence, unripe fruits are a richer reservoir of secondary metabolites and bioactive compounds than their ripe counterparts. Thus, this complex process from screening of phytoconstituents to identifying new leads for drug discovery requires well sophisticated analytical techniques, pharmacological knowledge, and in-silico computational approach.

The detailed procedure is illustrated in Figure 2.

4. BIOACTIVE COMPOUNDS IN SOME UNRIPE FRUITS

Based on plant species, genus, and family, the phytoconstituent present in them differs. The quantity of each secondary metabolite also varies with geographical location, stress condition, rainfall, soil, latitude, and other climatic factors. Literature review suggests the presence of a wide diverse array of phytoconstituents in the unripe fruits of coconut, Indian gooseberry, jackfruit, peas, and Bengal lemon. Table 2 indicates the phytoconstituents present in them.

Figure 3 corresponds to the compounds listed in Table 2.

Table 2

Bioactive compounds present in some unripe fruits.

| Sl. No. | Plant common name (Scientific name) | Phytoconstituents present | Class of bioactive compounds | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Unripe coconut/Daab (Cocos nucifera(L.)) | Concentration of carbohydrate is lesser in tender coconut water. Endospermic content results in higher nutrient content. | Endospermic content | (Lima et al., 2015; NyayiruKannaian et al., 2020; Padumadasa et al., 2016) |

| Pantothenic acid [1], Vitamin C [2], Biotin [3], Riboflavin [4], High concentration of mineral (Mn, Zn, P, K, Ca) | Nutrients | |||

| Catalase, Peroxidase, Diastase, Acid phosphatase | Enzymes | |||

| L-arginine [5], Isoleucine [6], Tyrosine [7], Arginine [8], Histidine [9], Aspartic acid [10], Glutamic acid [11] | Amino acid | |||

| Total alkaloid content 19.7 ± 0.32 mg/g, Skimmiwallin [12], Isoskimmiwallin [13] | Alkaloids | |||

| Kinetin [14], Zeatin [15], Auxin, cytokinin | Phytohormone | |||

| 2. | Indian gooseberry/Amlaki/Amla (Phyllanthus emblica) | Gallic acid [16], Ellagic acid [17], Quercetin, Kaempferol [18], Phyllaemblic acid [19], Cinnamic acid, Myricetin [20] | Polyphenols, Flavonoids | (Avinash et al., 2024; Chandrika et al., 2005; Dahiya & Dhawan, 2003; Gong et al., 2020; S.Kumar et al., 2017; B.Yang & Liu, 2014) |

| Pendunculagin, Emblicanin A [21], Emblicanin B, Punigluconin [22] | Tannins | |||

| Isostrictinin, Mallotusinin [23], Isomallotusinin, Phyllembilin, Phyllantin [24], Phyllantidine [25] | Alkaloids | |||

| Proline, Valine [26], Lysine, Aspartate, Alanine, Glutamic acid | Amino acids | |||

| D-Glucose, D-fructose, D-galactose, D-rhamnose | Carbohydrate | |||

| β-Sitosterol [27], Sigmasterol, Campesterol [28] | Steroids | |||

| 3. | Unripe jackfruit/Echor (Artocarpus heterophyllus) | Total phenolic content: 0.36 mg GAE/g. Includes Catechin, Epicatechin [29], Gallic acid, Chlorogenic acid, Protocatechuic acid [30] | Polyphenols | (Baliga et al., 2011; Chandrika et al., 2005; deFaria et al., 2009; Ranasinghe et al., 2019; SreejaDevi et al., 2021) |

| β-carotene [31], β-carotene, β-zeacarotene, β-carotene-5,6αepoxide, crocetin, 9-cis-violaxanthin [32. Gradually increase on ripening | Carotenoids | |||

| Moracin C [33], Moracin M [34], Moracin A [35], Atrocarpin, Jackalin [36] | Alkaloids | |||

| Norartocarpetin [37], Isoartocarpin, Morin, Cycloartenolol [38], Oxydihydroartocarpesin, Cynomacurin | Lectin | |||

| Artocarpin [39], Isoprenylchalcone | Glycosides | |||

| 4. | Green peas/Motorshuti (Pisum sativum) | Diosmin [40], Naringin, Apigenin [41], Epicatechin, Hespiridine, Myricetin, Rutin [42], Naringenin [43], | Flavonoids, Polyphenols | (Castaldo et al., 2021; Dahl et al., 2012; Ge et al., 2020; Guo et al., 2019; Hadrich et al., 2014) |

| Quercetin-3-rhamnoside [44], Isorhamnetin 3-rutinoside [45], Kapemferol 3-glucoside, Apigenin-7-O-glucoside | Glycosides | |||

| Pisatin [46], Lupanine [47], N-Methylcytisine, Sparteine [48] | Alkaloids | |||

| Ellagitannins, Proanthocyanidins, Gallotannins, Tannic acid | Tannins | |||

| Lutein, Alpha-carotene, Betacarotene, Violaxanthin, Neoxanthin | Caroteinoids | |||

| 5. | Bengal lemon/Gondhoraj lebu (Citrus limon) | Limonin [49]; nomilin | Limonoids | (Alam et al., 2014; Makni et al., 2018; Posadino et al., 2024; Shilpa et al., 2023; Tang et al., 2011) |

| Vitamin C, Manganese, Potassium, Copper | Minerals and nutrients | |||

| Catechin, Epicatechin, Proanthocyanidins, Tannic acid, Theaflavins | Tannins | |||

| Nomilin [50], Limonin, Melitidin [51], Naringenin [52], Hesperidin [53], Ergometrine [54], Synephrine [55], Eriocitrin [56] | Alkaloids | |||

| Quercetin glycosides; Limonin glucoside; Apigenin glycosides; Luteolin glycosides; Kaempferol glycosides | Glycosides | |||

| Quercetin; Hesperetin; Naringenin; Caffeic acid; Ferulic acid; P-coumaric acid; Chlorogenic acid [57]; Gallic acid; Rutin; Kaempferol; Luteolin [58]; Apigenin | Polyphenols and flavonoids | |||

| Aescin [59]; Dioscin; Escin [60]; Ginsenosides; Oleanolic acid saponins; Sarsasapogenin | Saponins |

5. CORRELATION OF ETHNOPHARMACOLOGICAL EFFECT ON BIOACTIVE COMPOUNDS

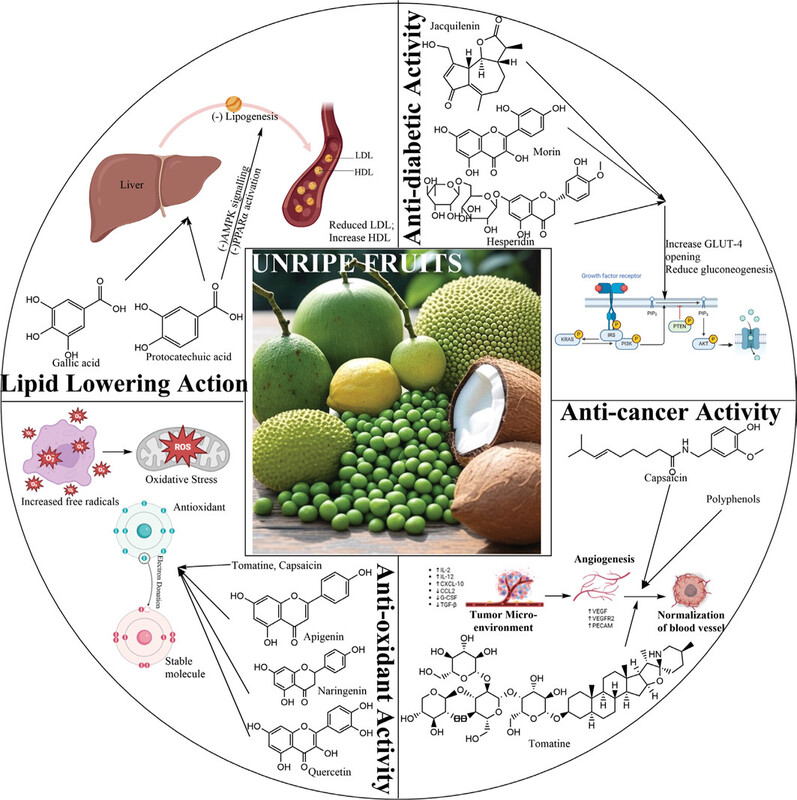

The compounds that are responsible for biological activity are called bioactive compounds. These bioactive compounds as discussed earlier are generally secondary metabolites. The link between the pharmacological effect and the folklore or the ethnomedicinal effect is attributed by the content of the secondary metabolites. The major pharmacological effects of the bioactive compounds present in some unripe fruits are:

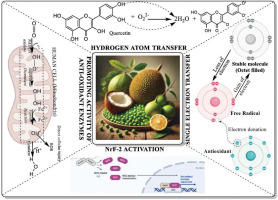

5.1. Anti-oxidant effect

In the human body, especially in mitochondria of the cell, oxidative pathway takes place (Liguori et al., 2018). The oxygen molecule that is transported by blood from lungs diffuses into the cell. In mitochondrial complex, oxygen is reduced to superoxide (O2-) by xanthine oxidase using an electron. This is then converted to hydrogen peroxide molecule by superoxide dismutase (SOD) enzyme (Cadenas & Davies, 2000). This enzyme requires two cofactors, manganese and copper. Deficiency of this manganese and copper results in the deficiency of SOD, which leads to accumulation of the superoxide molecule. Now, the hydrogen peroxide uptakes another electron to form a hydroxyl radical. This hydroxyl ion further takes an ion from the mitochondrial system to get reduced to water molecule by the action of an enzyme named catalase (CAT) (Holley et al., 2011). SOD and CAT are two prime indicators of anti-oxidant effect test (Islam et al., 2022). Since molecules like superoxide, hydroxyl radical, and hydrogen peroxide has excess electrons, they are called free radicals and this makes them capable of destroying and degrading the cells and tissue present in our body (Phaniendra et al., 2015). Thus, free radical scavenging is critically important to maintain a healthy well-being. Compounds that promote free radical scavenging by neutralizing the free radicals are called anti-oxidants (Alkadi, 2020). Anti-oxidants are generally polyphenolic or flavonoid molecules which have more than one hydroxyl group present in them (Alkadi, 2020).

Amla or Indian gooseberry and Bengal lemon are widely used for their citrus taste. This citrus taste is because of their content of rich polyphenols and ascorbic acid. Ascorbic acid being a polyphenolic vitamin commonly called vitamin C acts as a potent hydrogen atom donor to the different free radicals to neutralize them (Gęgotek & Skrzydlewska, 2023).

Phyllanthus emblica or Indian gooseberry is the richest source of Vitamin C. Apart from this, it contains rich amounts of ellagic acid, quercetin, gallic acid, and quercetin derivatives and their glycosides (Li et al., 2022). The single electron transfer mechanism followed by hydrogen atom abstraction to form stable peroxyl radical and reduce oxidative stress is the basic mechanism of the radical neutralization. Moreover, flavonoids cause genomic protection by inhibition of the DNA oxidative damage, prevent lipid peroxidation, and ensure protection of telomerase by reducing oxidative shortening of telomerase and preserving its activity (Prananda et al., 2023). Moreover, it causes reduction of 8-hydroxy-2’deoxyguanosine formation (Kroese & Scheffer, 2014). Certain enzymes like xanthine oxidase is inhibited, resulting in lesser formation of superoxide ion from oxygen molecules. Suppression of NADPH oxidase activity is also shown by polyphenols (Saini et al., 2022).

Bengal lemon on the other hand is a rich source of hesperidin and limonoids. Hesperidin h is a flavanone glycoside, naringenin or 5,7,4’-trihydroxyflavanone and Limonoids that are generally tetranortriterpenoids. The radical scavenging efficiency of these molecules is generally more than 80% (N. Singh et al., 2021). Another proposed mechanism of anti-oxidant effect is the prevention of protein oxidation. Bengal lemon inhibits and reduces protein carbonylation, ensures advanced oxidation protein products, and protects protein tertiary structure and critical sulfhydryl groups (Alam et al., 2014; Stabrauskiene et al., 2022), thus showing potent anti-oxidant activity.

Cocos nucifera or unripe coconut is a popular refreshing drink served to maintain a healthy life or to patients who are deprived of nutritious food, or in the case of electrolyte loss from the body (Devi & Ghatani, 2022). The primary anti-oxidant compounds present in it are gallic acid which have 3,4,5-trihydroxybenzoic acid structure, protocatechuic acid with 3,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid as the basic structure, and catechins which generally have Flavan-3-ol structural as their backbone (Nyayiru Kannaian et al., 2020). Phytochemicals responsible for the anti-oxidant effect of raw jackfruits include phenolic compounds with multiple -OH groups, carotenoids with conjugated double bond systems, and artocarpin which are prenylated flavonoid (Zeng et al., 2024). The radical scavenging pathway of these chemicals is similar to general proton donation to neutralize free radicals and formation of resonance-stabilized phenoxyl radicals to disrupt the radical chain propagation reaction that occurs in our body. Moreover, it is also seen that the compounds present in coconut water shows to modulate different enzymatic pathways (Li et al., 2018). It phosphorylates the Keap1 protein which in turn causes nuclear translocation of Nrf2 and hence binds to antioxidant response elements (ARE). Apart from the Nrf2 pathway activation, it shows an increase in the levels of enzymes like CAT, SOD, and Glutathione peroxidase (GSH) (Padumadasa et al., 2016). GSH is an enzyme that catalyzes formation of water from hydrogen peroxide without intermediate hydroxyl radical formation. Thus, the general equation of GSH catalyzed reaction is: GSH + H2O2 → GSSG + H2O. These compounds result in the formation of stable complexes from polyphenols and prevent Fenton reaction that catalyzes hydrogen peroxide to hydroxyl radical. The general equation of Fenton reaction is Fe2+ + H2O2 → Fe3+ + OH• + OH-. Formation of a lesser amount of hydroxyl radical and increase in the direct conversion of hydrogen peroxide to water molecule results in the reduction of oxidative stress (Padumadasa et al., 2016). The detailed insights of the mechanism is shown in Figure 4.

5.2. Anti-inflammatory and Immunomodulatory effects

Inflammation can be defined as a complex biological mechanism to defend the body from external stimuli like pathogens, damaged cells, or irritants (Kunnumakkara et al., 2018). It is the response of our immune system. The primary purposes of inflammation are to protect the body from infection and to initiate healing process and prevent further tissue damage. The inflammation can be understood by three different phases— initiation, propagation, and resolution phase (Chen et al., 2018; Soliman & Barreda, 2022).

The initiation phase is responsible to initiate the inflammation by recognizing potential stimuli which can generate the infection process in the human body (Sherwood & Toliver-Kinsky, 2004). The cellular recognition is done by three main processes. Pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), and toll-like receptor (TLR) activation. The propagation phase increases the inflammation as a response to the immune stimuli. It includes the molecular mediators. Pro-inflammatory cytokines like tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α); interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β) and interleukin-6 (IL-6); and chemokine recruitment and inflammatory cell migration are different stages and processes of molecular mediators (Doganyigit et al., 2022). The resolution phase is caused by the inflammation termination mechanisms. This includes anti-inflammatory cytokine production, lipid mediator class switching, and cellular apoptosis/clearance. Potential targets for anti-inflammatory achievements include cytokine modulation, NF-κB pathway inhibition, MAPK signaling suppression, and oxidative stress reduction, while cellular defense mechanisms include neutrophil activity regulation, macrophage phenotype modification, and T-cell inflammatory response control (Abdulkhaleq et al., 2018).

Anti-inflammatory activity is closely related to the anti-oxidant activity responsible to ameliorate the oxidative stress caused in the human body. Polyphenols like gallic acid, catechin, and quercetin are potential anti-inflammatory modulators (Cory et al., 2018). Unripe coconut and green peas have mild anti-inflammatory effects. The primary targets to reduce inflammation are the NF-κB pathway inhibition by direct transcription factor binding in order to prevent IκB kinase activation and thus it reduces pro-inflammatory gene expression (Aparisi et al., 2022). Cytokine modulation is another strategy which includes reduction and disruption of TNF-α production, IL-1β signaling, and macrophage inflammatory protein reduction. The third and last mechanism is oxidative stress mitigation as discussed earlier by ROS generation suppression, antioxidant enzyme enhancement, and mitochondrial inflammatory response control (Pisoschi et al., 2021; Poljsak, 2011).

Indian gooseberry or amla and Bengal lemon have similar strategies to reduce inflammation. This includes different mechanisms like IL-6 transcriptional suppression, TNF-α signaling pathway interruption, and IF-γ modulation. Moreover, there are strategies like inhibition of neutrophil migration, macrophage phenotype M1 to M2 transition, and reduction of inflammatory cell recruitment. Mast cell stabilization and inhibition of enzymes like COX-2 and 5-LOX pathway are potential anti-inflammatory mechanisms (Ndiaye et al., 2012; Rungruangmaitree & Jiraungkoorskul, 2017).

5.3. Anti-microbial and anti-bacterial activity

Nature is the source of remedies for all ailments. Microbial infection is one of the most prevalent diseases worldwide. Cultural, geographical, and personal hygiene are different factors that contribute to the growth of microbes and susceptibility to any sort of microbial attack. Antimicrobial activity is defined as the action of a substance to inhibit or seize the growth or microbes in their culture environment. When the anti-microbial agent is more specific to bacteria or to fungus, it is called an anti-bacterial and anti-fungal agent. The anti-microbial activity of unripe coconut or tender coconut is because of a peptide present in it called coconut antimicrobial peptides (CnAMPs). Moreover, the presence of a high amount of lauric acid is responsible for its anti-microbial activity. The anti-bacterial activity of coconut water was found to be comparable to ciprofloxacin. No in vitro activity of coconut water against Streptococcus mutans strain was observed (Rukmini et al., 2017). The following mechanism of anti-microbial activity of coconut water and citrus fruits like amla and Bengal lemon were found: Lipid bilayer destabilization of the bacterial cell membrane, increased membrane permeability to allow foreign drug material to enter and penetrate the cell membrane, and bacterial cell wall compromise as shown by β-lactam antibiotics. Moreover, it disrupts protein synthesis of the bacteria causing lysis of the bacteria. For Indian gooseberry, the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was 25–150 μg/mL for different gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria.

Jackfruit is also a potent anti-bacterial agent because of the presence of different components like Artocarpin and carotenoid compounds. Apart from conventional membrane disruption and inhibition of protein synthesis, the unripe fruit increases macrophages and promotes phagocytosis. Moreover, T-cell mediated humoral immunity also boosts up. The high anti-bacterial potency can be described by the MIC shown by it, which is 50–180 μg/mL for different bacterial strains. This fruit has potent anti-bacterial activity, strong anti-viral activity, but moderate to low anti-fungal activity.

5.4. Antidiabetic activity

Diabetes is a global problem, with rapid increase in its prevalence. Natural sources are now investigated to find potential sources of antidiabetic agents. It was found that several unripe fruits have considerable antidiabetic effects. Different species show different antidiabetic effects. The general mechanisms are caused by different polyphenolic compounds which include enhanced phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt 19 signaling cascade and hence opening of the GLUT-4 pathway to reduce blood glucose. This property is attributed to quercetin. Several enzyme modulations were shown by chlorogenic acid for reducing hepatic gluconeogenesis. The key enzymes involved are phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase and glucose-6-phosphatase. Gallic acid and ferulic acid reduce postprandial glucose absorption by reducing enzymes like β-amylase and alpha glucosidase. Epicatechin suppresses TNF-α and IL-6 production and other inflammatory mediators while caffeic acid reduces oxidative stress markers and causes pancreatic β-cell regeneration.

Coconut water which is a refreshing kernel with high endospermic content shows an antidiabetic effect by opening the GLUT-4 receptor and by downregulating glucose synthesis in liver. This increases glucose storage in the skeletal muscle. Indian gooseberry increases Nrf2 pathway to reduce inflammation. Insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1) is upregulated and inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β) was observed by the Amla fruit. Amla is a potent antidiabetic agent, which is consumed dried as an appetizer and also reduces blood sugar. It also modulates the AMPK-activated protein kinase (AMP) pathway. Hesperidin and naringenin of Bengal lemon interact and modulate insulin sensitivity by interacting with peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ). Eriocitrin increases the effectiveness of incretin hormone by inhibiting dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4). Limonene, which is the principal component of Bengal lemon, also enhances peripheral glucose utilization.

Raw jackfruit has an insulin mimicking capability. Jacalin mimics insulin molecular structure and hence causes insulin receptor interaction and mimics insulin signaling. Artocarpin enhances receptor binding affinity for glucose metabolism regulation. Peripheral glucose uptake is inhibited by morin which inhibits α-glucosidase enzyme. Dihydromorin facilitates GLUT4 translocation and promotes cellular glucose uptake. Green peas causes glycemic control since it is a protease inhibitor and modulates glucose metabolism. This property is shown by myoinositol. Pinitol improves insulin sensitivity and increases insulin receptor substrate phosphorylation. Phytic acid reduces intestinal glucose absorption while vicine modulates carbohydrate metabolism enzymes. The mechanistic insight of the antidiabetic effect of different compounds is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5

Mechanistic insight of the antidiabetic effect of different phytoconstituents of unripe fruits.

The different animal experimentation and human experimentation studies (in vivo) and in vitro studies are listed in Table 3.

Table 3

Animal experimentations and in vitro experiments conducted to demonstrate health benefits of different unripe fruits

| Sl. No. | Unripe fruits: Common name/Scientific name | In-vivo/in-vitroexperimentation | References | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model used | Experiment details | Observations | Inferences | |||

| 1. | Unripe coconut/Daab (Cocos nucifera(L.)); Arecaceae | Albino rats | Rats were divided into different groups. Vehicle control group was administered with distilled water. Negative control group with 1mL/kg CCl4, test group with 1mL/kg CCl4and 2-6mL/kg coconut water, respectively. | Increase in RBC, packed cell volume, HDL, SOD, CAT, albumin, and GSH levels. Decrease in WBC, LDL, VLDL, TC, TG, Urea, Bilirubin, and aspartate transaminases with P<0.05 for all cases | Hematological boosting property, Antihyperlipidemic activity, Antioxidant activity | (Elekwa et al., 2021) |

| In vitro Psoas muscles from Sprague Dawley rats | The muscles were incubated with distilled water (normal control), glucose (negative control), coconut water (test), and metformin (positive control) | Increase in muscle glucose uptake, GSH, CAT, SOD level Reduces ATPase, ENTDase, βglucosidase, and β-amylase Potential reduction in DPPH concentration Reduces malondialdehyde level | Antidiabetic activity, Anti-oxidant activity | (Erukainure & Chukwuma, 2024) | ||

| Wistar rats | Control group were administered with standard feed, negative control with 0.75% ethylene glycol to induce nephrolithiasis, test group with 0.75% ethylene glycol and 6 mL of coconut water | Inhibition of crystal deposition in the kidney and renal tissue, reduction in the number of crystals in urine, improves renal function, Reduces oxidative stress in the kidney | Nephroprotective activity | (Gandhi et al., 2013) | ||

| 2. | Indian gooseberry/Amlaki/Amla (Phyllanthus emblica); Phyllanthaceae | In vitro (Kidney of 2K1C rats) | 2.5% w/w methanolic extract of amla fruit was administered to the kidneys of 2K1C rats which had increased kidney wet weight, plasma creatinine, and uric acid | Reduction in creatinine and uric acid levels; reduction in malondialdehyde, NO, APOP to normal levels. Prevents fibrosis and entry of inflammatory cells, restores plasma anti-oxidant activities and prevents oxidative stress | Nephroprotective activity, Anti-oxidant activity | (Rahman et al., 2020) |

| Mice | Arsenic-induced hyper-glycemic mice (3mg/kg for 30 days) were used which altered glucose homeostasis and reduced glucose regulatory enzyme. Coadministration of amla fruit extract with arsenic was done to test group (500 mg/kg 30 days) to observe effect | Blood sugar level which increased because of arsenic was normalized with P<0.05. Hepatic regulatory enzymes of glucose like glucokinase, malic enzyme, and glucose-6 phosphate dehydrogenase was elevated. C-peptide protein also increased. Inflammatory markers like IL-β, TNF-βreduced with significant increase in CAT, GSH, and SOD | Antidiabetic activity, Anti-oxidant activity | (M. K.Singh et al., 2020) | ||

| Diabetic human volunteers | Albino rats | 50 normal and type II diabetic human volunteers were randomly selected. Three grams of amla fruit powder were administered orally to both the groups daily for about 30 days | Significant reduction in the fasting and 2h PP blood sugar level. Reduction of the total cholesterol level, TG level, LDL, and VLDL levels Improvement of HDL-C level and reduction of total lipid level | Antidiabetic effect Antihyperlipidemic effect | (Akhtar et al., 2011) | |

| All rats were made diabetic by injecting STZ. Five groups of rats were created. Vehicle-treated group received saline water, positive control received glibenclamide (10 mg/kg). Test group received amla powder (100, 200, and 400mg/kg). Blood parameters and histology were examined | Reduction in levels of HbA1C and MDA, increased number and size of pancreatic β–cell, increased expression of GLUT4, reduced levels of glucose-6-phosphatase and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase Increased GSH levels in liver. Increased level of oxidation of fatty acids (PPAR) Reduced lipogenic genes (SREBP1c, DGAT2), reduced total cholesterol levels | Antidiabetic activity Anti-oxidant activity Anti-hyper cholesterol activity | (Huang et al., 2023) | |||

| 3. | Unripe jackfruit/Echor (Artocarpus heterophyllus); Moraceae | Sprague Dawley strain pregnant female rats | Rats were induced with diabetes by STZ. Rats were divided into six groups. Normal control group administered with saline water, positive control with glibenclamide and test with ethanolic jackfruit extracts (100-400 mg/kg) for 14 days . | 70% reduction of blood glucose in the test group compared with the control, dose-dependent decrease of HbA1c and fasting glucose with highest decrease at 400 mg/kg and comparable to glibenclamide | Antidiabetic effect | (Dwitiyanti et al., 2019) |

| Albino rats | 150 mg/kg BW alloxan was administered to all rats making them diabetic. These rats were administered with 50, 100, and 150 mg/kg ethanolic extract of jackfruit for 21 days | After 21 days, reduction of weight and abnormal hematological features were observed. Reduced high serum level of lipids, creatinine, bilirubin, urea, and albumin level. | Antidiabetic activity, hepatoprotective activity, antihyperlipidemic activity | (Ajiboye et al., 2018) | ||

| Significantly reduced total cholesterol and total lipid level | Wistar rats | Ethanolic, n-butanolic, chloroform, and ethyl acetate extract of raw jackfruit were administered to diabetic rats (2 mL/kg) for 21 days | Significantly reduced fasting blood glucose (72%), increased insulin level (44%), reduced lipid peroxides (26%), HbA1c levels (28%), TG (37%), TC (19%), LDL (23%), and LDL/HDL ratio (39%) Increased SOD and CAT, reduced peroxidase | Antidiabetic activity, Antihyperlipidemic activity, Anti-oxidant activity | (Omar et al., 2011) | |

| 4. | Green peas/Motorshuti (Pisum sativum); Fabaceae | Mice model | Mice model was induced with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease by high fat diet. The green pea hull ethanolic extract was administered to the liver disease–induced mice model for about 14 days | Reduction in hepatic fact accumulation, improves GSH, SOD, and CAT level. reduction observed in the levels of AST and ALT , maintaining glucose metabolism and homeostasis because of reduction of glucose-6-phosphate and increase in GLUT-4 genetic expression. Vitamin B6 shows to inhibit PPAR and TLR4/NF-κB | Antidiabetic activity, hepatoprotective activity, anti-oxidant activity | (Guo et al., 2023) |

| 5. | Bengal lemon/Gondhoraj lebu (Citrus limon); Rutaceae | Wistar rats | The fruit extract was administered to STZ-Diabetic rat orally (200–400 mg/kg). Positive control was Glibenclamide. Serum biochemical parameters were measured | Dose-dependent reduction in blood glucose level, decreased lipid peroxidation level, reduced HbA1C levels, recovered GSH levels, increased CAT and SOD levels | Anti-oxidant activity, antidiabetic activity | (KunduSen et al., 2011) |

| Albino rats | Lemon fruit extract was administered to rats (10 mL/kg) with cyclophosphamide as negative control (10 mL/kg) to find histopathological changes in testes of male rats | Cyclophosphamide-treated rat showed changes in cross section of testes like pyknotic nuclei, spermatogenic necrosis, atrophy. When co-administered with lemon fruit extract, improvement was seen. | Anti-oxidant effect | (MohammedQuita, 2016), (Rahman et al., 2022) | ||

| Mice | Extract of the fruit of Bengal lemon was administered for 6 weeks. The negative control group was administered with only saline vehicle. | Scavenged 97% DPPH radical, significant reduction in blood glucose (P<0.001), higher serum insulin level, increased GLUT-4 and hepatic glucokinase level. PPAR β, γ and SREBP-1c levels. Glucose-6-phosphate and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase levels were reduced | Antidiabetic effect | (Chung et al., 2010) |

6. DISCUSSION

In today’s world where chronic disorders and ailments have overruled entire generations, the need to develop new molecules which can be promising to combat different secondary disorders have increased (Chakraborty et al., 2024). This in turn increased the quest to investigate and search for different bioactive molecules which can be originally derived from nature. Nature is the best source of bioactive compounds with least side effect and least adverse reaction with maximum benefit (Schneider et al., 2021). One of the promising natural sources which can be used to develop new pharmaceuticals and design new molecule is fruits in their unripe stage. These fruits in their unripe stage contain rich content of different phytoconstituents to prevent their harm and promote their defense from different predators. So, consumption of fruits in unripe stage can act as a potential remedy for several diseases (Nakitto et al., 2023).

This review touches upon the extensive use of five different unripe fruits as a source of potential phytoconstituent for future drug development and development of unique and novel molecules. Green coconut or unripe coconut is a popular refreshing drink all over the world that helps to keep our body hydrated because of its rich nutrient and endospermic kernel content (O’Brien et al., 2023; Segura-Badilla et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2024). It possesses some unique chemical constituents like skimmiwallin, isoskimmiwallin, keatin, and zenatin which are potentially responsible for its rich anti-oxidant activity. The endospermic nutrient content acts as a source for replenishing the lost electrolyte in dehydration and hence causes rehydration. Moreover, animal studies show that regular consumption of unripe coconut water causes more reduction in blood glucose and increase in the levels of antioxidant enzymes than that caused by the consumption of ripe coconut endosperm (O’Brien et al., 2023; Xu et al., 2022). Coconut has also a potential lipid-lowering capability and hence is often prescribed for patients with high total cholesterol levels (Sandhya & Rajamohan, 2006).

Indian gooseberry or amla is another fruit which is very much available for consumption in West Bengal and Odisha in India. Its rich sour taste prevents vomiting and nausea (Saini et al., 2022). Also, it has been found that its sour taste makes it a rich anti-oxidant source which is comparable to the antioxidant effects of different citrus fruits. The rich content of ascorbic acid and different polyphenols present in the fruit is responsible for the antioxidant activity. This ability occurs due to hydrogen atom donation from hydroxyl groups in the structure to the free radicals. This in turn stabilizes free radicals by single hydrogen atom transfer process (Mirunalini & Krishnaveni, 2010). Similarly, valence electron of the potentially capable antioxidant candidate is lost for the stabilization of the reactive species. This thereby reduces the oxidative stress and the pathway followed because of oxidative stress that includes tissue and cellular damage. The management of oxidative stress reduces the stress on pancreatic beta cell, which in turn can increase in size and regenerate for insulin synthesis. Amla along with green peas show increased genetic expression of GLUT-4 and reduce the expression of PPAR alpha. Thus, along with potential anti-oxidant activities, Indian gooseberries show remarkable anti-hyperglycemic activities too (Mirunalini & Krishnaveni, 2010; Variya et al., 2016).

Jackfruits which are among the largest fruits in the world are popular tropical fruits consumed in Eastern India and Bangladesh. It is consumed as fruit when ripe. When raw, it is cooked and consumed as a food (Trejo Rodríguez et al., 2021). Unlike ripe jackfruits, raw jackfruits have excellent antidiabetic properties. This is because of its excellent capability to mimic the insulin structure thanks to the presence of Jacklin. Atorcarpin and morin are potential molecules that lead to the opening of GLUT-4 and reduction of peripheral glucose uptake. On the other hand, the rich polyphenolic content of jackfruit and Bengal lemon make them potential anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant agents in nature (Ranasinghe et al., 2019). Flavonoids and polyphenols like quercetin, hesperidin, and naringenin present in Bengal lemon makes it a potential hydrogen atom donor to the unstable electron-rich free radicals to stabilize and ameliorate oxidative stress in our body. The eriocitrin present in Bengal lemon prevents utilization of peripheral glucose and manages glucose metabolism. The rich flavor of the Bengal lemon makes it extensively used in Indian subculture. This also leads to the reduction of obesity and manages total cholesterol in blood, as it can reduce peripheral fat deposition and lipid accumulation (Klimek-Szczykutowicz et al., 2020; Islam et al., 2022).

Screening of these several unique bioactive phytoconstituents that are responsible for different pharmacological action can create a library of compounds for further use. These compounds along with the preexisting compounds can be naturally docked using several computational approaches to extend the knowledge of their interaction with different receptors present in the human body in order to deduce new pharmacological actions which might be involved with the molecule which was not known before. These bioactive compounds based on docking with different endogenous proteins can be used to develop a pharmacophore followed by a drug moiety by side chain and backbone modification and hence can open a new array of pharmaceuticals.

7. CONCLUSION

Nature is the source of all potential remedies that have been ever used by mankind. Be it plants and plant products, animals, or other natural substances, nature plays a significant role in ameliorating different diseases. So, the primary focus of different pharmaceutical chemists and other researchers are on natural products to derive different secondary metabolites or bioactive components responsible for eliciting biological responses and refining them to form new novel pharmaceuticals having higher efficacy and potency in treatment of diseases without excess side effects. Unripe fruits, because of their vast phytoconstituent storage for self-defense opens a new array of drug development. Jacklin present in Artocarpus heterophyllus can act as an excellent antidiabetic while CnAMP present in coconut can be an important molecule to combat several microbial diseases. These natural compounds need to be refined by computational approaches like QSAR in their chemical structure to increase their specificity and potency. Future research can be extended to screen the relevant compounds obtained from different unripe fruits which have a binding affinity to human proteins involved in the pathogenesis of diseases to find newer, naturally derived molecules that can either act as agonists or antagonists, thereby forming new pharmaceuticals with immense importance to mankind.

ABBREVIATIONS

CnAMPs – Coconut Antimicrobial Peptides

PAMPs – Pathogen-Associated Molecular Patterns

DAMPs – Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns

TLR – Toll-Like Receptor

TNF-α – Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha

IL-1β – Interleukin-1 beta

IL-6 – Interleukin-6

NF-κB – Nuclear Factor Kappa B

MAPK – Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase

ROS – Reactive Oxygen Species

IF-γ – Interferon-gamma

COX-2 – Cyclooxygenase-2

5-LOX – 5-Lipoxygenase

MIC – Minimum Inhibitory Concentration

PI3K – Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase

IRS-1 – Insulin Receptor Substrate-1

GSK-3β – Glycogen Synthase Kinase-3 beta

AMPK – AMP-Activated Protein Kinase

PPAR-γ – Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor-gamma

DPP-4 – Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4

RBC – Red Blood Cell

HDL – High-Density Lipoprotein

SOD – Superoxide Dismutase

CAT – Catalase

WBC – White Blood Cell

LDL – Low-Density Lipoprotein

VLDL – Very Low-Density Lipoprotein

TC – Total Cholesterol

TG – Triglycerides

DPPH – 2,2-Diphenyl-1-Picrylhydrazyl

NO – Nitric Oxide

APOP – Apoptosis

PP blood sugar – Postprandial Blood Sugar

SREBP1c – Sterol Regulatory Element-Binding Protein-1c

DGAT2 – Diacylglycerol O-Acyltransferase 2

AST – Aspartate Aminotransferase

ALT – Alanine Aminotransferase

TLR4/NF-κB – Toll-Like Receptor 4/Nuclear Factor Kappa B

MCP-1 – Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1

iNOS – Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase

Klf4 – Kruppel-Like Factor 4

HbA1C – Glycated Hemoglobin (Hemoglobin A1C)

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Authors thanks their respective institutions for providing opportunity to conduct the review.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Amitesh Chakraborty did research concept and design, writing of the article, and critical revision of the article. Santanu Giri was responsible for research concept and design and writing of the article. Shubhadeep Hazra looked into research concept and design, collection and/or assembly of data, and writing of the article. Aniruddha Sarkar was involved in research concept and design, data analysis and interpretation, and critical revision of the article. Parnasree Chakraborty did data analysis and interpretation and writing of the article. Tushar Adhikari did critical revision of the article and accorded the final approval of the article.