1. INTRODUCTION

Skin aging, particularly in the context of photoaging, constitutes a significant dermatological and public health issue predominantly influenced by prolonged exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation (Chen et al., 2021). In contrast to intrinsic aging, which unfolds naturally over time, photoaging is a consequence of environmental factors, notably solar UV radiation, that precipitate premature structural and functional degradation of the skin (Zhang & Duan, 2018). Clinically, photoaged skin is distinguished by pronounced wrinkles, coarse texture, dyspigmentation, reduced laxity, and diminished elasticity, all of which are fundamentally rooted in extensive molecular and cellular impairment within the dermal layer (Ansary et al., 2021). Global estimates indicate that approximately 80-90% of observable skin aging in areas exposed to sunlight can be directly linked to UV radiation, positioning it as the primary modifiable risk factor associated with cutaneous aging (Al-Sadek & Yusuf, 2024).

As the UV index levels continue to escalate globally, the prevalence of photoaging is correspondingly increasing. The World Health Organization (WHO) documents a consistent rise in UV exposure attributed to the depletion of the ozone layer, coupled with climate change phenomena (Parker, 2020). In equatorial and tropical regions, particularly Southeast Asia, where daily UV index levels often surpass 10 (designated as extreme), the associated risk intensifies considerably (Valappil et al., 2024). In Indonesia, the combination of high solar exposure throughout the year and the lack of public awareness regarding sun protection measures has resulted in a notable increase in the manifestation of premature aging signs, even among younger demographics (Goh et al., 2023). Furthermore, lifestyle determinants such as outdoor employment, recreational sun exposure, and urban air pollution exacerbate the phenomenon of photoaging by fostering oxidative environments that heighten UV-induced skin injury (Song et al., 2024). Present preventive strategies, including the application of sunscreen, frequently fall short due to issues such as inconsistent usage, photoinstability, or inadequate coverage against long-term molecular damage, thereby underscoring the necessity for adjunctive strategies that offer both protective and reparative capabilities in the cellular sense (Gupta et al., 2023).

The essential system that triggers skin damage from ultraviolet (UV) rays is oxidative stress (Wei et al., 2024). Ultraviolet A and B (UVA and UVB) rays invade the skin’s outer and inner layers, resulting in a surge of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that go beyond the protective capacity of intrinsic antioxidant defenses (Chen et al., 2021). This inconsistency ignites lipid peroxidation, results in protein denaturation, leads to DNA strand fragmentation, and activates MMPs (matrix metalloproteinases), especially MMP-1 and MMP-3, which promote the degradation of elastin and collagen structures (Feng et al., 2024). Furthermore, UV exposure promotes the release of inflammatory mediators, including nitric oxide (NO) and various cytokines, while promoting the enzymatic function of hyaluronidase (HAase), which catalyzes the depolymerization of hyaluronic acid, a pivotal glycosaminoglycan integral to dermal hydration and extracellular matrix (ECM) stability (Salminen et al., 2022). Collectively, these biochemical events compromise the dermal ECM, expedite fibroblast senescence, and contribute to the observable signs of photoaging. Consequently, agents that possess antioxidant properties and preserve the ECM are crucial for the prevention and management of photoaged skin (Gupta et al., 2023).

In light of this necessity, increasing scientific emphasis has been placed on investigating bioactive constituents derived from natural origins. exhibiting antioxidant, regenerative, and anti-inflammatory characteristics (Fernandes et al., 2023). Salmon DNA, extracted from the reproductive tissues of fish, is abundant in nucleotides and demonstrates significant antioxidant capabilities by neutralizing free radicals and facilitating DNA repair mechanisms (Lee et al., 2024). Its considerable polyanionic charge allows for enhanced water retention and the formation of protective biofilms, which improve skin hydration and serve as a molecular barrier against environmental stressors (Pitassi et al., 2024). Additionally, salmon DNA has been demonstrated to promote fibroblast proliferation, collagen production, and tissue regeneration (Sveen et al., 2023). When synergistically combined with bioactive plant compounds, these beneficial effects may be further amplified (Pellacani et al., 2024). The serum formulation examined in this investigation comprises five botanical extracts: Camellia sinensis (green tea), Aloe vera, Rosa spp., Centella asiatica, and Matricaria chamomilla, each selected for its recognized role in dermal protection (Michalak, 2023). The catechins found in green tea, such as EGCG, are potent antioxidants and inhibitors of MMP activity; the polysaccharides from A. vera facilitate wound healing and enhance fibroblast function; R. damascena contributes vitamin C and polyphenols that stabilize collagen; C. asiatica is rich in triterpenoids that promote ECM synthesis; and M. chamomilla exerts anti-inflammatory effects through bisabolol and chamazulene (Melnyk et al., 2024).

Regardless of the promising individual actions of these components, the synergetic effects of these agents within a unified topical serum remain inadequately examined, especially in the context of biologically relevant UV-induced stressors (Zhao et al., 2025). Previous research largely focused on isolated substances or failed to integrate mechanistic insights pertaining to antioxidant and anti-aging parameters (Bjørklund et al., 2022).

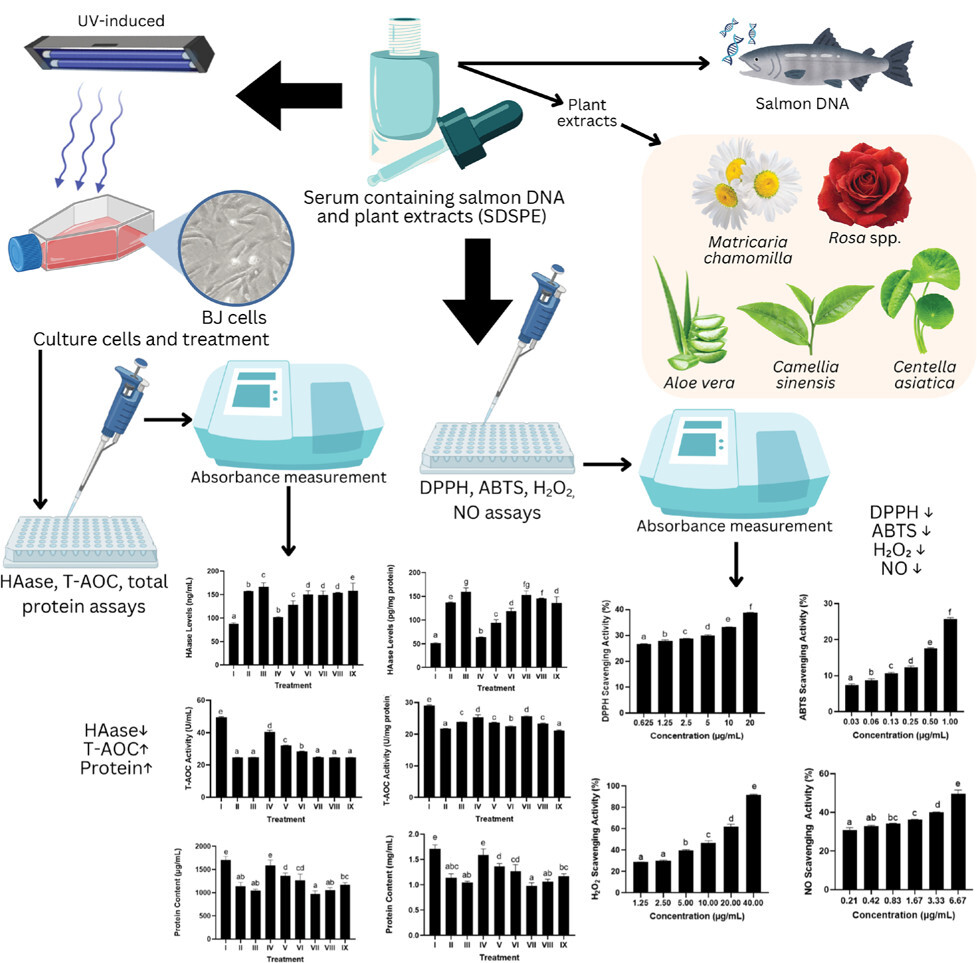

This research aims to assess the effectiveness of protective and revitalizing serum formulation featuring salmon DNA and designated plant extracts on UV-exposed human skin fibroblast (BJ) cells. The parameters evaluated include free radical scavenging capacity (DPPH, ABTS), inhibition of NO (nitric oxide) and H2O2 (hydrogen peroxide), hyaluronidase (HAase) inhibition, total antioxidant capacity (T-AOC), and maintenance of total protein levels. These comprehensive assays facilitate a thorough evaluation of the serum’s effectiveness in alleviating the molecular signatures of photoaging, thereby providing valuable insights into its potency as a multitargeted dermocosmetic agent (Wei et al., 2024).

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. SDSPE Preparation

SDSPE was formulated using extracts of C. sinensis (green tea), A. vera, Rosa spp. (rose flowers), C. asiatica (gotu kola), and M. chamomilla (chamomile flowers). The dried plant materials were sourced from a certified vendor and individually milled into fine powders. Extraction was conducted using 70% ethanol, following stringent Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) guidelines. This process was carried out through a collaborative effort involving PT Aretha Medika Utama (Bandung), in partnership with PT FAST (Depok), a licensed manufacturer of traditional medicine. Following extraction, lactose was incorporated into the resulting paste, which was then dried, ground into powder, and stored at room temperature (Widowati et al., 2023).

2.2. Formulation of SDSPE

SDSPE was manufactured by PT Dizza Karya Utama, located in Bogor, Indonesia. The formulation incorporated botanical extracts including C. asiatica (gotu kola), A. vera, M. chamomilla (chamomile), C. sinensis (green tea), and Rosa spp. (rose flower). In addition to these plant-based ingredients, several bioactive compounds were included in the formulation, such as allantoin, salmon DNA, niacinamide, tranexamic acid, a ceramide complex, and collagen.

2.3. Serum Base Formulation

The serum base was produced by PT Dizza Karya Utama, located in Bogor, Indonesia. Unlike the SDSPE formulation, the serum base did not include botanical extracts such as C. sinensis (green tea), C. asiatica (gotu kola), A. vera, M. chamomilla (chamomile), or Rosa spp. (rose flowers). Instead, it was formulated with specific active ingredients, including allantoin, niacinamide, tranexamic acid, a ceramide complex, and collagen.

2.4. DPPH Scavenging Activity

Five different final concentrations of the samples (20, 10, 5, 1.25, and 0.63 µg/mL) were prepared. For each concentration, 50 µL of the SDSPE sample was dispensed into wells of a 96-well microplate. Then, 200 µL of 0.077 mmol DPPH solution (Sigma-Aldrich, D9132), previously dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), was added to initiate the reaction. The mixtures were gently mixed and incubated in the dark at room temperature for 30 min. After incubation, absorbance was recorded at 517 nm using a microplate reader (Multiskan™ GO Microplate Spectrophotometer, Thermo Scientific). A 250 µL DPPH solution was used as the negative control, while 250 µL methanol was used as the blank (Widowati et al., 2018).

2.5. ABTS-reducing Activity

The antioxidant activity of SDSPE was assessed using the ABTS radical cation decolorization method, with 2,2’-azinobis-(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) diammonium salt (Sigma, A1888-2G) serving as the oxidizing agent. The test samples were prepared in five concentrations (1, 0.5, 0.25, 0.13, 0.06, and 0.03 µg/mL). 2 μL of each sample was added to a 96-well microplate, followed by 198 µL of the ABTS•+ solution. The reaction mixtures were incubated at 30°C for 6 min, after which absorbance was measured at 745 nm using a microplate reader. Antioxidant capacity was determined by calculating the IC50 value, which represented the concentration required to inhibit 50% of the radical activity (Prahastuti et al., 2019).

2.6. H2O2 Scavenging Activity

To evaluate hydroxyl radical scavenging activity, a reaction mixture was assembled by adding 12 µL of 1 mM ferrous ammonium sulfate (Sigma, 7783859), 60 µL of SDSPE at different concentrations (40, 20, 10, 5, 2.5, and 1.25 µg/mL), and 3 µL of 5 mM hydrogen peroxide (Merck, 1.08597.1000). The mixture was incubated in the dark at room temperature for 5 min. After that, 75 µL of 1 mM 1,10-phenanthroline (Sigma, 131377) was added to each well, including blanks. The plate was then kept in the dark for another 10 min at room temperature. Absorbance was recorded at 510 nm to determine the hydroxyl radical scavenging potential (Prahastuti et al., 2019).

2.7. NO Scavenging Activity

Nitric oxide (NO) generation was initiated by dissolving sodium nitroprusside (SNP) (Merck, 106541) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (Gibco, 1740576), adjusted to pH 7.2 to mimic physiological conditions. Under aerobic conditions, NO reacts with oxygen to form stable compounds such as nitrite and nitrate. The concentration of NO was assessed using the Griess reagent method. A 10 mM SNP solution was combined with different concentrations of SDSPE (6.67, 3.33, 1.67, 0.83, 0.42, and 0.21 µg/mL). These mixtures were incubated for 2 h at room temperature (approximately 26°C). After incubation, Griess reagent comprising 1% sulfanilamide (Merck, 1117999), 2% phosphoric acid (Merck, 100573), and 0.1% N-(1-naphthyl) ethylenediamine dihydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich, 2224888) was added. The absorbance was then measured at 546 nm to evaluate the NO concentration (Irwan et al., 2020).

2.8. BJ cell culture and UV induction

BJ human fibroblast cells (ATCC® CRL-2522™) were acquired from Aretha Medika Utama (Bandung, Indonesia). In accordance with standard protocols, the cells were cultured in complete Minimum Essential Medium (MEM; Biowest, L0416-500) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Biowest, S1810-500). Cellular aging was induced in BJ cells at approximately 80% confluency using UVB irradiation for 75 min at a total dose of 300 J/cm2. Following UVB exposure, cells were treated with various formulations of SDSPE and a serum base (SB) as part of the experimental protocol (Girsang et al., 2023; 2024; 2025).

2.9. Hyaluronidase Assay

Hyaluronidase (HAase) activity was quantified using an Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA), following the manufacturer’s instructions provided with the Human HAase ELISA Kit (E-EL-H2201; Elabscience, Houston, TX, USA). The absorbance was then measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Multiskan™; Thermo Fisher Scientific) (Widowati et al., 2024).

2.10. Total Antioxidant Capacity Assay

T-AOC was assessed using the T-AOC assay kit (E-BC-K219-M; Elabscience, Houston, TX, USA), adhering to the protocols delineated by the manufacturer. The assay hinges on the capacity of antioxidants present within the sample to convert Fe3+ to Fe2+, which subsequently interacts with TPTZ (2,4,6-tripyridyl-s-triazine) to yield a colored complex. The depth of the blue coloration developed exhibits a direct correlation with the T-AOC present in the sample.

The final sample concentrations used were SDSPE (3.13, 6.26, and 12.5 µg/mL) and serum base (0.82, 1.56, and 3.13 µg/mL), along with positive and negative controls (UV induction + no treatment), and vehicle control (UV induction + basal medium). Diluted samples were mixed with the T-AOC working solution in a 96-well microplate and incubated at 37°C for 10 min. Subsequently, absorbance was measured at 593 nm using a microplate spectrophotometer. The results were assessed based on the protein concentration of the corresponding sample (Girsang et al., 2023; 2024; 2025).

2.11. Total Protein Assay

A standard solution was prepared using 2 mg of bovine serum albumin (BSA) (A9576, Lot. SLB2412; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). Subsequently, 20 µL of the standard, quercetin samples, and 200 µL of Quick Start™ Dye Reagent 1 (5000205; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) were dispensed into each well. The microplate was then incubated at ambient temperature for 5 min. The absorbance was recorded at 595 nm using a microplate spectrophotometer (Multiskan GO; Thermo Fisher Scientific) (Lister et al., 2020).

2.12. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS software (version 20.0), and the results were presented as mean ± standard deviation. The normality and homogeneity of the data were assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk and Levene’s tests, respectively. For normally distributed data with homogeneous variances, one-way ANOVA was applied, followed by Tukey’s HSD post hoc test. When data failed to meet parametric assumptions, the Kruskal-Wallis test was used, with pairwise comparisons conducted by the Mann-Whitney U test. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. DPPH Scavenging Activity

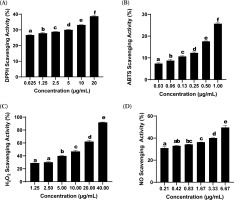

Based on the results, the formulation SDSPE exhibited significant DPPH radical scavenging activity. At 20 µg/mL, the sample demonstrated an inhibitory activity of 38.71 ± 0.23%. The corresponding IC50 value was calculated to be 38.73 ± 0.59 µg/mL (Table 1), reflecting a moderate level of antioxidant activity. As illustrated in Figure 1A, all concentrations tested showed significant differences (p < 0.05), as indicated by different superscript letters (a-f).

Figure 1

Effects of various concentrations of serum formula on DPPH, ABTS, H2O2, and NO assay. Different letters above the bars indicate statistically significant.

Table 1

The IC50 of SDSPE Toward DPPH, ABTS, NO, and H2O2 scavenging.

| Samples | Equation | R2 | IC50 µg/mL |

|---|---|---|---|

| DPPH | y = 0.5942x + 26.987 | 0.99 | 38.73 ± 0.59 |

| ABTS | y = 18.373x + 7.7144 | 0.99 | 3.56 ± 0.53 |

| NO | y = 2.7271x + 31.43 | 0.99 | 6.84 ± 0.54 |

| H2O2 | y = 1.6027x + 28.99 | 0.99 | 3.11 ± 0.39 |

[i] The antioxidant activity of the sample was assessed through DPPH, ABTS, nitric oxide (NO), and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) radical scavenging assays. For each method, the linear regression equation, coefficient of determination (R2), and IC50 values (µg/mL) were determined. The IC50 value indicates the concentration required to inhibit 50% of radical activity. All measurements were conducted in triplicate and are presented as the mean ± standard deviation.

3.2. ABTS-reducing Activity

The serum formulation showed a marked ability to scavenge ABTS radicals depending on the dose. Scavenging activity of 25.70 ± 0.40% was observed at 1.00 µg/mL, which was the maximum among all tested concentrations. The calculated IC50 value was 3.56 ± 0.53 µg/mL, indicating potent antioxidant activity (Table 1). Figure 1B demonstrates that incremental increases in concentration led to a statistically significant augmentation of the radical scavenging activity (p < 0.05), as indicated by different superscript letters (a-f).

3.3. H2O2 Scavenging Activity

The hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) scavenging assay demonstrated a dose-dependent enhancement in radical neutralization capacity. Figure 1C shows that the highest level of inhibition was observed at a concentration of 40.00 µg/mL, yielding a scavenging percentage of 91.91 ± 0.50%, which was significantly greater than that at the lowest concentration tested (1.25 µg/mL; 28.90 ± 0.03%, p < 0.05). Statistically significant differences among the various concentrations were marked by distinct alphabetical annotations (a-e). The IC50 value for H2O2 scavenging was determined to be 3.11 ± 0.39 µg/mL, with a strong linear correlation indicated by an R2 value of 0.99 (Table 1).

3.4. NO Scavenging Activity

The nitric oxide (NO) radical scavenging assay exhibited a concentration-dependent enhancement in inhibitory activity. As illustrated in Figure 1D, the peak scavenging effect was recorded at 6.67 µg/mL, reaching 49.67 ± 1.90%, which was significantly greater than the activity measured at 0.21 µg/mL (30.99 ± 1.16%, p < 0.05). Statistical evaluation indicated significant differences across the tested concentrations, as denoted by distinct alphabetical markers (a-e). The IC50 value for NO scavenging was calculated at 6.84 ± 0.54 µg/mL, supported by a strong linear correlation (R2 = 0.99) based on regression analysis (Table 1).

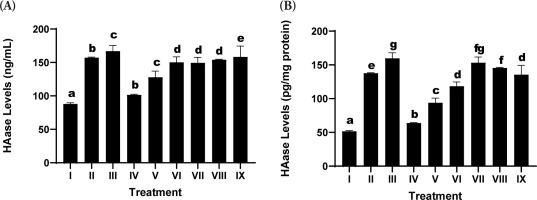

3.5. Hyaluronidase Assay

Hyaluronidase (HAase) expression, a critical enzyme responsible for hyaluronic acid degradation within the ECM, was significantly upregulated in the UV-exposed positive control group (Treatment II) relative to the nonirradiated negative control (Treatment I), thereby confirming the degradative impact of UV radiation on dermal structural integrity (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Effects of various concentrations of the serum formulation on hyaluronidase (HAase) activity. (A) HAase levels expressed as ng/mL. (B) HAase levels normalized to total protein (pg/mg protein). Treatment groups are as follows: I (negative control), II (positive control), III (vehicle control; UV induction+basal medium), IV (SDSPE 3.13 µg/mL), V (SDSPE 6.25 µg/mL), VI (SDSPE 12.5 µg/mL), VII (serum base 0.82 µg/mL), VIII (serum base 1.56 µg/mL), and IX (serum base 3.13 µg/mL). Different lowercase letters above the bars indicate statistically significant differences between groups, as determined by the Mann-Whitney U test (p < 0.05). Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (n = 4).

The SDSPE serum resulted in a significant attenuation of HAase levels in a dosage-dependent manner. The minimum concentration of SDSPE (3.13 µg/mL; Treatment IV) produced a suppression of HAase expression that approached levels observed in the negative control group at 101.56 ± 1.04 µg/mL, indicating a strong inhibitory effect on ECM degradation. This suggests potential anti-aging properties of the formulation at this dose. These findings indicate that the inhibitory effect on HAase is preserved across a range of concentrations, but is most effective at lower doses, potentially due to optimal cellular interaction with active compounds without triggering stress responses. In contrast, the serum base treatments (VII-IX) were associated with higher HAase levels, showing only marginal suppression compared to the control positive. These results underscore that the anti-HAase activity is primarily attributable to the SDSPE components rather than the serum base.

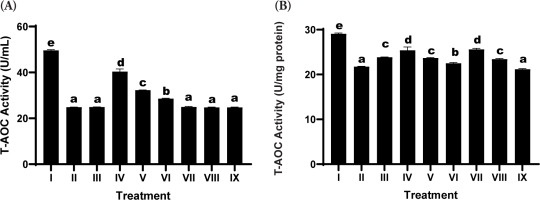

3.6. Total Antioxidant Capacity Assay

The evaluation of T-AOC demonstrated a marked reduction in the UV-irradiated positive control group relative to the negative control, indicating oxidative stress-induced impairment of the cellular antioxidant defense system (Figure 3). Treatment with the SDSPE serum led to a significant restoration of T-AOC levels relative to the positive control. Among the tested concentrations, the lowest dose (3.13 µg/mL; Treatment IV; SDSPE serum) resulted in the highest enhancement of antioxidant capacity, approaching the values observed in the negative control group. This suggests that a low concentration of SDSPE serum is sufficient to activate endogenous antioxidant defenses without inducing cytotoxic effects. In contrast, the serum base treatments (VII-IX) elicited comparatively modest increases in T-AOC, with no statistically significant difference from the positive control group in most cases.

Figure 3

Effects of various concentrations of serum formula on T-AOC activity. (A) T-AOC activity expressed as U/mL. (B) T-AOC activity normalized to total protein (U/mg protein). Treatment groups: I (negative control), II (positive control), III (vehicle control; UV induction + basal medium), IV (SDSPE 3.13 µg/mL), V (SDSPE 6.25 µg/mL), VI (SDSPE 12.5 µg/mL), VII (serum base 0.82 µg/mL), VIII (serum base 1.56 µg/mL), and IX (serum base 3.13 µg/mL). Different lowercase letters above the bars denote statistically significant differences between groups, as determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test (p < 0.05). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (n = 4).

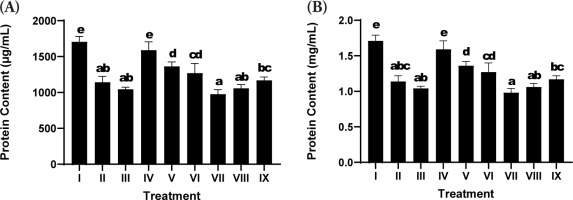

3.7. Total Protein Content

Total protein content was assessed as a general indicator of cell viability, biosynthetic activity, and ECM production in fibroblast cultures. Exposure to UV (positive control; Treatment II) led to a decrease in the total protein content relative to the nonirradiated negative control group (Treatment I), suggesting the detrimental effect of oxidative stress on cellular protein synthesis and structural integrity (Figure 4). Treatment with SDSPE serum at a concentration of 3.13 µg/mL (Treatment IV) significantly reinstated total protein levels, reaching values comparable to the negative control group (1588.55 ± 117.8 µg/mL), thereby suggesting a protective or reparative role against UV-induced protein depletion.

Figure 4

Effects of various concentrations of serum formula on protein content. (A) Total protein levels expressed as µg/mL. (B) Total protein levels normalized to volume, expressed as mg/mL. Treatment groups are as follows: I (negative control), II (positive control), III (vehicle control; UV induction + basal medium), IV (SDSPE 3.13 µg/mL), V (SDSPE 6.25 µg/mL), VI (SDSPE 12.5 µg/mL), VII (serum base 0.82 µg/mL), VIII (serum base 1.56 µg/mL), and IX (serum base 3.13 µg/mL). Statistical differences among groups were denoted by distinct lowercase letters above the bars, based on analysis using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc comparison (p < 0.05). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (n = 4).

Higher concentrations of SDSPE serum (6.25 and 12.5 µg/mL; Treatments V and VI) also promoted increases in protein levels compared to the positive control, although to a lesser extent than the lowest concentration. These findings suggest that lower doses are optimal for stimulating fibroblast protein expression, possibly due to hormetic responses or concentration-dependent cellular tolerance to the bioactive compounds.

In contrast, cells treated with the serum base (Treatments VII-IX) exhibited lower protein content, which showed no statistically significant difference compared to the positive control group, reinforcing that the observed effects were attributable specifically to the bioactive components of SDSPE rather than the vehicle alone.

4. DISCUSSION

The SDSPE formulation exhibited notable radical scavenging activities, evidenced in the ABTS and DPPH assays, and demonstrated a strong capacity to neutralize oxidative species. These outcomes align with previous studies reporting the antioxidant potential of salmon DNA and polyphenol-rich plant extracts through hydrogen donation and electron transfer mechanisms (Huang et al., 2023). The potent antioxidant activity is likely attributable to the synergistic effect of biologically active constituents, which include nucleotides, flavonoids, and polyphenols, which can improve redox balance by quenching free radicals and upregulating endogenous antioxidant defense systems such as SOD and GPx (Chen et al., 2021).

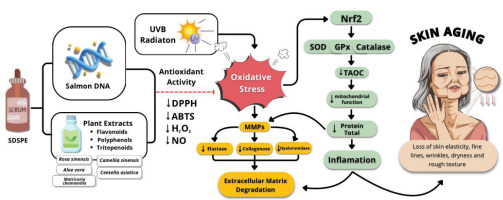

The reduction in oxidative stress markers also reflects the ability of SDSPE to limit UV-induced ROS generation, which plays a pivotal role in triggering cellular senescence and ECM degradation (Panich et al., 2016). The antioxidant bioactive compounds in SDSPE activate Nrf2 signaling, leading to increased expression of downstream protective enzymes, although this mechanism requires further validation (Boo, 2020).

Beyond broad-spectrum free radical scavenging, SDSPE demonstrated pronounced efficacy in neutralizing hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), a key ROS implicated in oxidative injury to cellular membranes and genomic integrity. The scavenging activity was dose-dependent, and the relatively low IC50 value observed reflects a high reactivity toward H2O2. These results suggest that SDSPE can enhance cellular resistance against peroxides, potentially through catalase-like activity or stimulation of endogenous antioxidant enzymes, mechanisms that are often mediated via Nrf2 pathway activation (Ngo & Duennwald, 2022).

Nitric oxide (NO) scavenging was also observed, although with slightly lower potency compared to other radicals. NO, while playing physiological roles in signaling, becomes cytotoxic when overproduced during oxidative stress, particularly in conjunction with superoxide to form peroxynitrite (Andrabi et al., 2023). The ability of SDSPE to reduce NO levels suggests potential anti-inflammatory and cytoprotective effects, likely attributable to its phenolic constituents and nucleic acid-derived compounds acting as NO inhibitors (Rahman et al., 2021). This is specifically relevant in the context of UV-derived skin damage, whereby NO overproduction leads to inflammation and apoptosis (Ryšavá et al., 2021).

A significant modulation of hyaluronidase (HAase) activity was observed following SDSPE treatment. Inhibition of HAase suggests preservation of HA (hyaluronic acid), the main ECM ingredient involved in skin elasticity and hydration (Al-Halaseh et al., 2022). This effect is consistent with reports on natural inhibitors of HAase, particularly polyphenols, which protect ECM integrity by limiting HA degradation (Hering et al., 2023). The reduced HAase activity implies potential anti-aging benefits of the serum through maintenance of dermal matrix structure (Quiles et al., 2022). Mechanistically, the downregulation of HAase expression may be attributed to the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties of the serum’s bioactive constituents (Michalak, 2022). C. asiatica and C. sinensis, in particular, are known to inhibit ECM-degrading enzymes through polyphenolic and triterpenoid compounds, while salmon DNA has been suggested to promote tissue repair and modulate gene expression related to matrix integrity (Fjelldal et al., 2024).Moderate reductions in HAase were also observed at concentrations of 6.25 µg/mL (Treatment V) and 12.5 µg/mL (Treatment VI), with significant improvement over the positive control, though less pronounced than Treatment IV. These findings indicate that the inhibitory effect on HAase is preserved across a range of concentrations, but is most effective at lower doses, potentially due to optimal cellular interaction with active compounds without triggering stress responses.

The increase in T-AOC further supports the systemic antioxidant effect of SDSPE. Enhanced T-AOC in treated groups indicates an improved cellular defense system capable of counteracting UV-induced oxidative burden (Gieniusz et al., 2024). Similar patterns have been documented in studies evaluating botanical formulations that stimulate endogenous antioxidant enzymes and replenish intracellular glutathione levels (Tumsutti et al., 2022). This suggests that the antioxidant enhancement is predominantly attributable to the bioactive constituents in the SDSPE formulation, which consist of salmon-derived DNA and phytochemical-rich plant extracts such as C. sinensis, C. asiatica, M. chamomilla, A. vera, and Rosa spp., which are known to contain flavonoids, polyphenols, and other antioxidant compounds (Kandasamy et al., 2023). Together, these findings confirm that SDSPE is not only capable of broad-spectrum antioxidant action in acellular assays but also demonstrates cellular protective effects, as supported by the increase in T-AOC in fibroblasts. This improvement in T-AOC is likely linked to the activation of cellular antioxidant systems and the reduction of intracellular ROS levels (Halliwell, 2023). Collectively, these findings highlight the ability of the SDSPE, particularly at a low concentration, to restore antioxidant capacity in UV-induced fibroblasts toward physiological levels, emphasizing its capacity to attenuate oxidative damage contributing to skin aging.

Total protein content in fibroblasts with SDSPE treatment suggests enhanced cellular function and metabolic activity (Merecz-Sadowska et al., 2021). This improvement is indicative of increased fibroblast biosynthesis capacity, likely reflecting elevated ECM protein expression, such as elastin and collagen. Enhanced protein synthesis is critical for tissue repair and regeneration and has been linked to reduced oxidative stress and improved mitochondrial function (Drabik et al., 2021). The observed increase in total protein is consistent with the previous findings on marine-derived peptides and nucleotide-enriched extracts promoting fibroblast proliferation and collagen deposition (Cadar et al., 2024). The observed increase in total protein following SDSPE treatment is consistent with the reported regenerative properties of its ingredients. Salmon-derived DNA has been associated with cellular repair and proliferation, while plant-derived compounds such as C. asiatica, A. vera, and C. sinensis are known to stimulate collagen synthesis and enhance fibroblast activity (Merecz-Sadowska et al., 2021). The restoration of protein levels may therefore reflect a synergistic interaction among these components, promoting ECM remodeling and cellular homeostasis in UV-compromised skin fibroblasts (Liang et al., 2023). This enhancement in protein synthesis may reflect improved cellular metabolic function and ECM production, potentially linked to the bioactive properties of the serum formulation. The results show that SDSPE has a better anti-aging effect than basic serum, with the optimal concentration being 3.13 µg/mL.

A key thrust of this research is the use of multiple complementary assays to evaluate both antioxidant activity and ECM-related anti-aging markers. The use of human fibroblast BJ cells provides a relevant in vitro model for dermal aging (Gerasymchuk et al., 2022). However, the studies are limited by the lack of mechanistic assays, such as gene or protein expression of antioxidant enzymes or ECM regulators. Future studies incorporating Nrf2, MMPs, COL1A1, and HA synthase expression could provide deeper mechanistic insights.

Figure 5 shows that SDSPE (Serum containing Salmon DNA and Plant Extracts) exerts protective effects against UVB-induced skin aging. UVB radiation triggers oxidative stress, leading to increased ROS and the activation of MMPs, such as elastase, collagenase, and hyaluronidase (Girsang et al., 2024). This enzyme degrades the ECM, contributing to inflammation and skin aging symptoms, including loss of fine lines, elasticity, wrinkles, dryness, and rough texture (Gunadi et al., 2025). SDSPE, rich in antioxidant compounds such as flavonoids, polyphenols, and triterpenoids from plant extracts and salmon DNA, enhances antioxidant activity by reducing DPPH, ABTS, H2O2, and NO radicals. It also triggers the Nrf2 signaling cascade, resulting in the enhanced expression of endogenous antioxidant enzymes (SOD, catalase, and GPx), which improves mitochondrial function and reduces total protein degradation and inflammation (Girsang et al., 2025). Collectively, these actions preserve ECM integrity and attenuate signs of photoaging.

5. CONCLUSION

The SDSPE formulation demonstrated potent antioxidant and anti-aging properties in UV-induced human dermal fibroblasts, as evidenced by its ability to scavenge multiple reactive species, inhibit hyaluronidase activity, enhance T-AOC, and promote protein synthesis. These effects are likely mediated by the synergistic action of bioactive components, including salmon-derived DNA and polyphenol-rich plant extracts, which collectively mitigate oxidative stress and preserve ECM integrity. These findings underscore the promise of SDSPE as a multifunctional dermocosmetic candidate with protective and restorative effects against photoinduced skin damage. Nonetheless, further in-depth mechanistic investigations and in vivo assessments are essential to substantiate its clinical relevance and clarify the molecular mechanisms involved.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Aretha Medika Utama, Biomolecular and Biomedical Research Center, Bandung, Indonesia, for their generous support in providing the materials essential for the successful completion of this research.

FUNDING

This research was funded by Maranatha Christian University, Bandung, Indonesia, through an international research collaboration with Chungnam National University, Daejeon, Republic of South Korea.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors affirm that there are no potential conflicts of interest associated with the publication of this research.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

WW conceived and designed the research, supervised the overall study workflow, and contributed to manuscript drafting. RT coordinated the research process and assisted in data interpretation. PO performed the data analysis and led the manuscript writing. MKN and DNT carried out the data collection, laboratory procedures, and assisted in drafting the manuscript. DSH and GA contributed to data curation, interpretation, and literature review. RA and KSA provided technical validation, supervised analytical methods, and critically revised the manuscript. HSU reviewed the final formatting of the draft manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.