1. INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory conditions pose significant challenges to global health, making them a crucial focus of pharmaceutical and medical research. Inflammation is basically the body’s natural immune response to harmful agents like injured cells, pathogens, toxic substances, and radioactivity (Chen et al., 2018; Medzhitov, 2010). The primary role of inflammatory reaction is to eliminate these damaging stimuli and start the healing process (Ferrero-Miliani et al., 2007). At the tissue level, the classic signs of inflammatory response include redness, swelling, pain, heat, and tissue dysfunction, which triggered by local immune cells, blood vessels, and activation of inflammatory mediators (Chen et al., 2018). In spite of the availability of various treatments, current anti-inflammatory medications often come with limitations, particularly when used in the long term, leading to potential toxic effects on the gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, renal, and hematologic systems (Ghlichloo and Gerriets, 2023; Wan et al., 2021).

Emerging evidence suggests that plants are a valuable source of anti-inflammatory agents (Nunes et al., 2020), particularly because of their phenolic contents (Puangpraphant et al., 2022). Polyphenols are secondary metabolites produced by plants, functioning as a vital part of their defense mechanisms against environmental stressors such as radiation and diseases (Rahman et al., 2021). Phenolic compounds are known to activate antioxidant pathways, which are closely associated with their anti-inflammatory effects (Puangpraphant et al., 2022). These bioactive compounds inhibit the secretion of lysozyme and β-glucuronidase from neutrophils, and also reduce the release of arachidonic acid, leading to a decrease in inflammatory responses (Hussain et al., 2016). Furthermore, polyphenols have been shown to inhibit several key enzymes involved in pathological processes, including the transcription factor NF-κB, the activating protein-1 (AP-1), lipoxygenase (LOX), xanthine oxidase (XO), cyclooxygenase (COX) (Hussain et al., 2016).

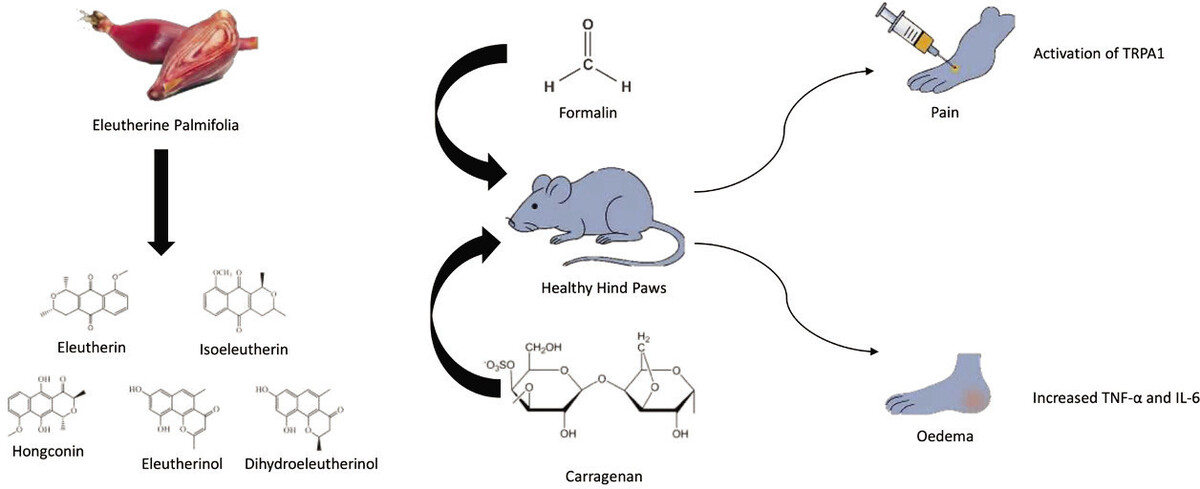

One plant particularly rich in phenolic compounds is Eleutherine palmifolia (L.) Merr. This plant is native to Borneo Island, Indonesia, but can also be found elsewhere in South America and South East Asia regions (Arbain et al., 2022). E. palmifolia is recognized for its anticancer (Mutiah et al., 2020), antibacterial, antidiabetic, and anti-inflammatory properties (Arbain et al., 2022). To date, the investigation into the anti-inflammatory properties of E. palmifolia extract has been largely confined to in vitro studies. Earlier research has demonstrated the anti-inflammatory effects of E. palmifolia extract and its compounds through the stabilization of red blood cell membranes (Paramita and Nuryanto, 2018) or inhibition of lipopolyaccharides-activated macrophages (Han et al., 2008; Song et al., 2009). Building on these findings, this study aimed to examine the phytochemical component of E. palmifolia ethanolic extract and evaluate its antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects using an in vivo mouse model.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Materials

All drugs and chemicals, such as Ibuprofen (Pharmaceuticals Laboratories), were procured from a local drug store in Makassar, Indonesia. Formalin in Phosphate Buffer Solution (PBS) as well as Λ-Carrageenan (Tokyo Chemical Industry) were purchased from a chemical distributor in Makassar, Indonesia. E. palmifolia bulbs were obtained from Samarinda, East Kalimantan Province, Indonesia.

2.2. Extract Preparation

A total of 4 kg of fresh bulbs were processed, yielding 1.8 kg of simplicia powder. The powder was subsequently dehydrated in a conventional oven (50°C) for 48 hours. The extraction process involved macerating the powdered bulbs in 96% ethanol for three consecutive days. The resulting filtrate was concentrated using a rotary evaporator until a thick extract was attained.

2.3 Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrophotometry (GC-MS) analysis

The composition of E. palmifolia extract was analyzed following a previously described method (Djabir et al., 2023) using a Thermo Scientific Trace 1310 gas chromatograph and TSQ 8000 Evo mass spectrometer (Mundelein, IL, USA).

2.4 Animals

Male albino mice (weighing 20–45 grams) were acclimated in a well-ventilated laboratory environment with a 12-hour dark–light cycle for 2 weeks before initiating the in vivo experiment. All mice had continuous access to food and water ad libitum. All animal protocols were conducted based on standard protocols for laboratory animal handling and obtained ethical approval number 305/UN4.17/KEP/2024.

2.5 Formalin-Induced Nociceptive

The formalin test was employed to assess the antinociceptive effects of E. palmifolia extract. E. palmifolia extract was orally administered at doses of 250 mg/kg, 500 mg/kg, and 750 mg/kg. For comparison, ibuprofen was administered at a dose of 15 mg/kg, while water served as the placebo control. Thirty minutes post-administration, mice received an intraplantar injection of 1% formalin in Phosphate Buffer Saline (PBS) solution (50 µL) into the hind paw. The pain responses were meticulously recorded for 60 minutes, with two independent observers quantifying pain-induced behaviors such as paw-licking and paw-stamping (Mewar et al., 2023).

2.6 Carrageenan-Induced Acute Inflammation

In this experiment, mice were arranged in five treatment groups. One group received distilled water only to serve as placebo. Treatment groups were administered an oral dose of E. palmifolia extract at either 250 mg/kg, 500 mg/kg, or 750 mg/kg dose, and one additional group received a 15 mg/kg dose of ibuprofen. Paw edema was induced by 10 μL of 1% carrageenan subplantar injection. Immediately after the injection, the extract or ibuprofen was administered via oral gauge. Paw edema was then assessed using a plethysmometer at 1, 2, 3, and 4-hour intervals. Blood samples were withdrawn before the rats were euthanized at the end of the experiment.

2.7 Measurement of serum hs-CRP

The collected blood samples were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for a duration of 30 minutes to obtain its serum. The resulting serum was preserved at -20°C until analysis. Serum level of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) was measured with an enzyme-linked immunosorbent (ELISA) assay using a Mouse CRP ELISA Kit (Elabscience, United States). The serum level of hs-CRP was expressed as mg/L.

2.8 Statistical Analysis

Results were reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The data normal distribution was tested using the Shapiro-Wilk test. The mean differences of normally distributed data were compared using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and subsequently, post-hoc comparisons were conducted using Tukey’s HSD test. A significance of p<0.05 was defined for all statistical analyses.

3. RESULTS

3.1 GC-MS analysis

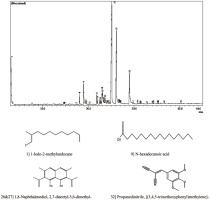

GC-MS analysis identified 1,8-Naphthalenediol, 2,7-diacetyl-3,6-dimethyl (C16H16O4) as the most abundant phenolic compound in the E. palmifolia extract, represented by peaks 26 and 27, with a combined concentration of 58.23%. The second most prevalent compound was Propanedinitrile, [(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)methylene] - (peak 32), accounting for 9.52% of the extract. In addition, 1-Iodo-2-methylundecane (peak 1) and N-hexadecanoic acid (peak 9) were detected, contributing 9.12% and 5.33%, respectively. The detail of chemical compounds and their respective retention times are provided in Table 1, and the corresponding GC-MS chromatogram is presented in Figure 1.

Table 1

The chemical compounds detected in Eleuthrine palmifolia extract using Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry.

3.2 The effects of E. palmifolia extract on formalin-induced pain

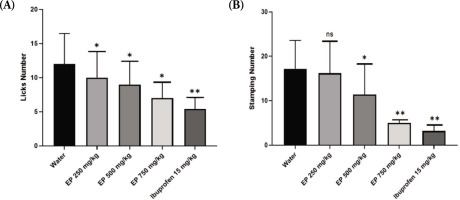

The administration of E. palmifolia extract at doses of 250 mg/kg, 500 mg/kg, and 750 mg/kg immediately after formalin injection demonstrated significant antinociceptive effects by markedly reducing the number of paw licks in mice. Figure 2A illustrates the comparison of licking response among treatment groups. Within the first 10 minutes post-formalin injection, the average number of paw-licking responses in the group that only received water was 12.00 ± 4.47. Treatment with E. palmifolia extract at doses of 250 mg/kg, 500 mg/kg, and 750 mg/kg resulted in a significant reduction in paw-licking responses in mice (p<0.05). Notably, ibuprofen produced a much greater reduction in licking response compared to the E. palmifolia extract and the water groups (p< 0.01).

Figure 2

The number of paw-licking (A) and paw-stamping (B) observed within 60 minutes of intraplantar formalin injection. *p<0.05; **p<0.01 compared to the water-treated group.

In addition, E. palmifolia extract also markedly reduced the number of paw-stamping in mice (Figure 2B). The lowest dose (250 mg/kg) of E. palmifolia extract did not show a significant difference compared to water treatment. However, at the middle dose (500 mg/kg), E. palmifolia extract treatment led to significantly decreased paw stamping response compared to the water group (p<0.05). The reduction in paw-stamping was even more pronounced in the group treated with 750 mg/kg of E. palmifolia extract (p<0.01), similar to that treated with ibuprofen.

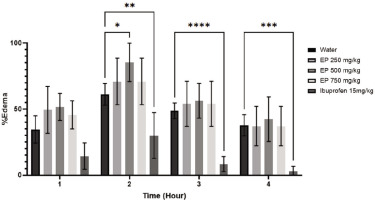

3.3 The effects of E. palmifolia extract on carrageenan-induced swelling

One hour after carrageenan injection, noticeable changes in the paws were observed, including redness and swelling. These conditions were present in all mice during the first hour regardless of the treatment given. As depicted in Figure 3, the volume of paw edema increased and peaked at 2 hours post-injection in both the water control and E. palmifolia–treated groups. Following the peak, the edema volume began to gradually decrease after 3 and 4 hours. Notably, in the ibuprofen-treated group, the volume of paw edema started to reduce as early as 2 hours post-carrageenan injection compared to the water-treated group (p<0.05). A significant reduction in paw edema was observed in all E. palmifolia–treated groups only after 4 hours (p<0.05). By this time, the ibuprofen-treated group had completely resolved swelling while the sign of edema was still persisting in the water-treated group (p<0.01).

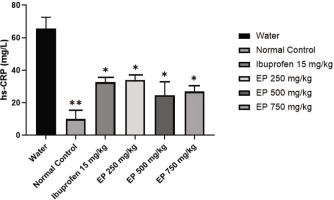

3.4 The effects of E. palmifolia Extract on hs-CRP

As illustrated in Figure 4, carrageenan injection significantly elevated serum hs-CRP levels 4 hours post-injection. The mean hs-CRP level in the water-treated group reached 65.59 ± 7.06 mg/L, which is approximately four times higher than the mean hs-CRP level in the normal control group (p<0.01). In comparison, the hs-CRP levels in the E. palmifolia–treated groups were significantly reduced to 33.91 ± 3.22 mg/L at a dose of 250 mg/kg, 24.54 ± 8.29 mg/L at 500 mg/kg, and 26.90 ± 3.59 mg/L at 750 mg/kg. A significant decrease in hs-CRP levels was also observed in the ibuprofen-treated group relative to the water-treated group (p < 0.05), comparable to that observed in the 750 mg/kg E. palmifolia extract-treated group.

5. DISCUSSION

Inflammation is a natural defense mechanism by which the body responds to foreign substances. During this process, pro-inflammatory pathways are activated, leading to the release of cytokines and the activation of immune cells such as macrophages and lymphocytes, which are crucial for phagocytosis (Watkins et al., 1995). Inflammation also involves tissue destruction, increased vascular permeability, and the activation of leukocytes. In addition, pro- inflammatory mediators are released, including bradykinin, prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), and various cytokines (Maletic and Raison, 2012). Subsequently, these mediators stimulate prostaglandin synthesis and release sympathetic monoamines. All these processes contribute to a hyper-nociceptive response, lowering the pain threshold, and causing hyperalgesia (Machelska and Stein, 2003).

In this study, the administration of E. palmifolia extract significantly reduced formalin-induced pain and suppressed carrageenan-induced paw edema. Formalin is widely used in animal models to study pain. It has been shown that formalin increases sensory nerve stimulation by activating transient receptor potential ankyrin 1 (TRPA1) receptors resulting in pain sensation (Macpherson et al., 2007). The results indicated that the dose of 750 mg/kg of E. palmifolia extract was particularly effective in reducing pain, as shown by the significant decrease in paw licking and stamping in mice. This antinociceptive effect was nearly comparable to that of ibuprofen, a standard nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug. In line with this finding, a previous study has also demonstrated the anti-rheumatoid arthritis effects of E. palmifolia extract in a Complete Freund’s Adjuvant (CFA) model (Muthia et al., 2023).

The extract of E. palmifolia also exhibited efficacy in reducing paw edema induced by a 1% carrageenan injection. Carrageenan is widely used to develop inflammatory models in rodents because of its rapid and reliable induction of inflammation (Mewar et al., 2023). Intraplantar injection of carrageenan is known to increase the expression and release of various cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1, and IL-6 (Yang et al., 2015), which subsequently trigger the release of additional pro-inflammatory mediators, including leukotrienes, arachidonic acid metabolites, immunoglobulin E, and C-reactive protein (CRP) (Abd-Allah et al., 2018). These cytokines play a crucial role in the immune response by activating leukocytes and protecting against tissue damage.

In this present study, E. palmifolia extract effectively reduced paw edema across all administered doses. However, the onset of its anti-inflammatory effects was delayed, becoming significant only after 4 hours, compared to the faster onset observed in the ibuprofen-treated group at 2 hours. The extract also demonstrated the ability to suppress CRP, a pro-inflammatory mediator. CRP is upregulated during inflammation in response to increased interleukin-6 (IL-6) secreted by activated macrophages and T cells. By binding to lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) on the membranes of apoptotic or necrotic cells, CRP facilitates immune recognition and activates the complement system (Sproston and Ashworth, 2018). The reduced CRP levels observed in all groups treated with E. palmifolia extract further supported its anti-inflammatory properties. In line with this, a previous study has shown that E. palmifolia extract significantly reduces colitis-associated colon cancer in mice (Mutiah et al., 2020). Moreover, another study has shown that E. palmifolia may also inhibit IL-1 activity in an osteoarthritis rat model (Sari et al., 2023).

The anti-nociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects of E. palmifolia are likely attributed to its high phenolic content. In this study, 43 chemical compounds were detected in the ethanolic extract of E. palmifolia, with phenolic compounds comprising over 50% of the total extract. The most abundant compound was 1,8-Naphthalenediol, 2,7-diacetyl-3,6-dimethyl-, which has been shown to possess potent antioxidant properties (Foti et al., 2002; Manini et al., 2018). Another key compound, Propanedinitrile, [(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)methylene]-, a nitrile derivative, has been reported to elicit anticancer, anti-apoptotic, and anti-inflammatory activities (Haviv et al., 1988; Kim et al., 1989; Pojarová et al., 2007). In addition, N-hexadecanoic acid or palmitic acid was also detected. This fatty acid is well-documented for its anti-inflammatory activity (Aparna et al., 2012), and its inhibition on pro-inflammatory mediators such as IL-8, IL-6, and PGE2 may enhance the anti-nociceptive activity of the extract (Yelugudari et al., 2023). Interestingly, 1-Iodo-2-methylundecane was also detected. This oestrogen-like compound has not previously been reported in E. palmifolia ethanolic extract (Fridayanti et al., 2022; Munaeni et al., 2019). In fact, the benefits of phytoestrogens in reducing inflammatory responses and related diseases have been demonstrated earlier (Barsky et al., 2021; Chavda et al., 2024), which may add to the potential therapeutic applications of E. palmifolia extract for managing inflammation, oxidative stress, and pain.

6. CONCLUSION

It is concluded that E. palmifolia extract, particularly at a 750 mg/kg dose, is effective in providing both antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects in mice, indicated by reduced pain response, decreased swelling, and diminished serum hs-CRP level. The analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects of E. palmifolia are more likely because of its high phenolic content, particularly 1,8-Naphthalenediol, 2,7- diacetyl-3,6-dimethyl-. These findings may offer scientific support for the potential development of this traditional remedy as a pain reliever and anti-inflammatory agent. However, the specific mechanisms underlying these effects require further investigation.

LIMITATION

While this study demonstrates the promising antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory potential of E. palmifolia extract in mice, several limitations should be acknowledged. The research was limited to animal models, and thus the findings may not directly translate to human physiology without further validation. Although the GC-MS analysis identified major bioactive constituents, such as 1,8-Naphthalenediol, 2,7-diacetyl-3,6-dimethyl-, the specific molecular pathways through which these compounds exert their effects remain unclear. In addition, the study focused solely on acute models of pain and inflammation, leaving the extract’s efficacy in chronic or long-term conditions unaddressed. Safety profiling, including potential toxicity and side effects at higher doses or with prolonged use, was also not assessed. Future research should include mechanistic and toxicity studies of E. palmifolia to further elucidate its potential use as a natural analgesic and anti-inflammatory agent.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors express their gratitude to the Drug Efficacy and Medication Safety Research Group for the support and facilities offered throughout the course of this study.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization was done by LH and YYD; Data collection was the responsibility of NIK, SKN, and UK; Data analysis and interpretation were the concern of NIK, SKN, UK, and YYD; Manuscript writing was looked into by NIK, UK, and YYD; Proofreading and editing were done by SKN, AK, YYD.