1. INTRODUCTION

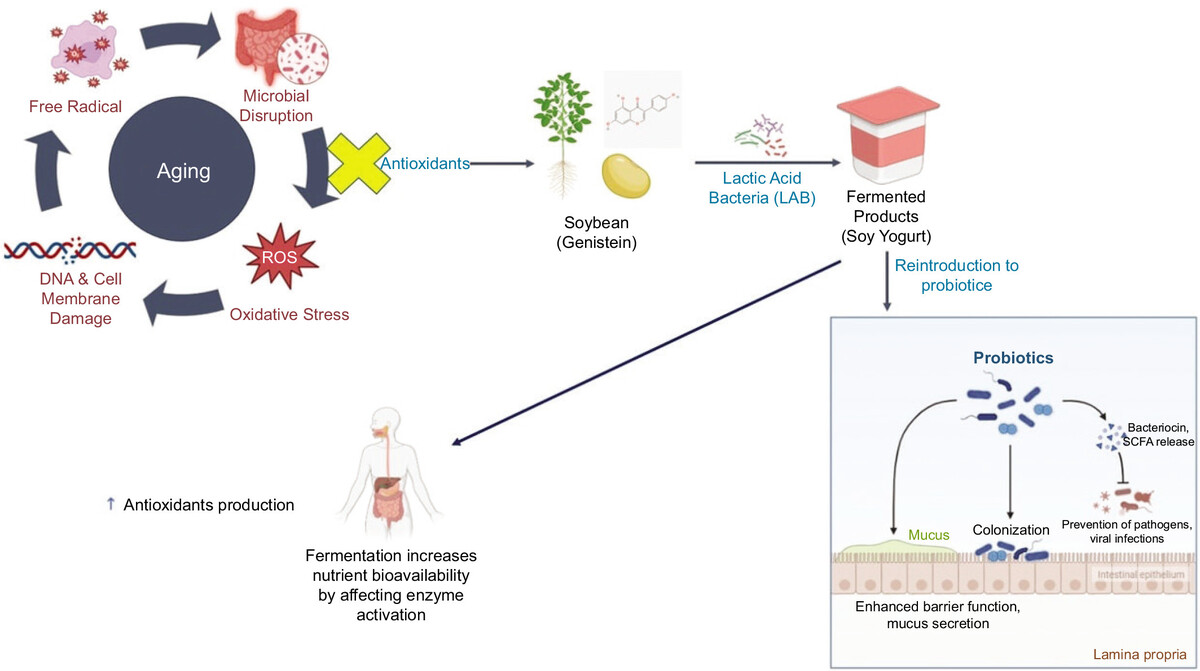

Aging is a physiological process characterized by a gradual decline in the ability of tissues and organs to repair and maintain their structure and function, particularly in the human body. This process begins around the ages of 25–30 years and occurs at both the organ and cellular levels. As individuals age, physiological changes in the immune system and organs accumulate, leading to a condition known as frailty. Increased frailty in older adults heightens their vulnerability to immune dysfunction, infections, and metabolic imbalances. One significant imbalance associated with aging is the disruption of the microbiome, which consists of various bacteria, fungi, and viruses that inhabit the body (El Chakhtoura et al., 2017). The microbiome plays a crucial role in overall health, including its influence on the aging process. Current research focuses on the relationship between brain function, the microbiome, and aging to promote healthy aging and slow the aging process. One key mechanism in this area is the brain–gut axis. The current studies show that the diversity and abundance of gut microbiome species decline with age, starting around 36 years, leading to microbiome imbalances and increased oxidative stress, contributing to gastrointestinal diseases such as inflammation (Leite et al., 2021).

Inflammation can be influenced by intrinsic factors, such as genetics and age, and extrinsic factors, including lifestyle, diet, and environmental exposure. External factors like UV radiation and pollution can accumulate free radicals, causing oxidative stress and DNA damage, ultimately accelerating aging. Antioxidants are essential for combating these effects, and soybeans are recognized for their high antioxidant content, particularly in the form of isoflavones. These compounds are secondary metabolites in soybeans that are known for their potent antioxidant activity. Various processing methods, including fermentation, have been employed to enhance the quality and activity of soybean isoflavones (Masternak & Yadav, 2022; Mohajeri, 2019). Soybean fermentation is an effective and relatively inexpensive technique for improving the nutritional quality of soybeans. One notable product of soybean fermentation is soy yogurt, which has been shown in both in vitro and in vivo studies to act as a natural antioxidant, reducing oxidative stress and inflammation. Soy yogurt is produced by fermenting soybeans with lactic acid bacteria (LAB), which convert isoflavones into bioactive compounds that are more easily absorbed by the body. LAB, such as Lactobacillus spp., Bifidobacterium spp., and Streptococcus thermophilus, are commonly used as yogurt starters and are defined by the FAO/WHO as live microorganisms that confer health benefits when consumed in adequate amounts (Awad et al., 2005; do Prado et al., 2022).

These three bacteria also exhibit antibacterial properties by producing compounds such as hydrogen peroxide and bacteriocins, which inhibit harmful microorganisms. In soy yogurt, LAB fermentation enhances isoflavone levels, increases antioxidant activity and helps to balance the microbiome. This balance and the brain–gut axis may contribute to slowing the aging process and improving health. Lactobacillus casei is a facultatively heterofermentative LAB capable of converting glucose into lactic acid and other metabolites. However, its potential as an antioxidant and antibacterial agent in fermented soy products remains underexplored in Indonesia (Parasthi et al., 2020; Yamamoto et al., 2019). Thus, this study aimed to combine the fermentation of Bifidobacterium longum and Streptococcus thermophilus, commonly used in various commercial yogurts, with Lactobacillus casei to produce soy yogurt with enhanced antibacterial and antioxidant properties. The resulting functional food is expected to decelerate aging and provide significant health benefits.

2. METHODS

This study investigated the production and antibacterial activity of soybean yogurt fermented with varying concentrations of Lactobacillus casei, Streptococcus thermophilus, and Bifidobacterium longum. Soybeans (100 g) were soaked in water (1:2 ratio) for 12 hours, blended with water (1:8 ratio), and strained. The resulting soybean milk was mixed with 35 g of sugar and skim milk to a final volume of 1,000 mL, homogenized, and pasteurized at 80°C for 20–30 minutes before cooling to 45°C (Nizori et al., 2008).

Bacterial strains were inoculated separately in MRS broth and incubated at 37°C for 24–48 hours. Starter cultures were prepared by adjusting the bacterial suspensions to match the McFarland standard 0.5. Fermentation was perfoarmed sterile soybean milk at 37°C for 24 hours, with formulations varying by L. casei concentration:

Y0, S. thermophilus : B. longum : L. casei = 2:2:0

Y1, S. thermophilus : B. longum : L. casei = 2:2:1

Y2, S. thermophilus : B. longum : L. casei = 2:2:2

Y3, S. thermophilus : B. longum : L. casei = 2:2:4

The fermented samples were centrifuged (5,800 × g, 5 min, 4°C), and the supernatants were subjected to antibacterial and antioxidant tests (Putri et al., 2020).

2.1. Kirby–Bauer disk diffusion method

The antibacterial activity was assessed using the disk diffusion method against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli on MHA plates. Negative controls included blank disks and clindamycin served as a positive control. The inhibition zones were categorized as high (>23 mm), moderate (17–22 mm), weak (11–16 mm), or inactive (<11 mm).

2.2. DPPH method

DPPH or 2,2-diphenyl-1-(2,4,6-trinitrophenyl) hydrazyl is a method based on the reduction of purple DPPH radicals through a hydrogen atom transfer mechanism (Muthia et al., 2017; Oliveira et al., 2011). This reduction changes the color, stabilizing the molecule into yellow DPPH2 as the DPPH radicals are reduced. The remaining purple DPPH was measured using a spectrophotometer at 515–520 nm wavelength to determine antioxidant activity. For this test, a DPPH solution with a concentration of 6×10–5 M was prepared by dissolving 1.182 mg of DPPH in 50 mL of methanol. The DPPH solution was mixed with the test substance, homogenized, and incubated at room temperature for 30 minutes. The absorbance was measured using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer at a maximum wavelength of 517 nm, with measurements repeated three times (Hu et al., 2022).The antioxidant activity was expressed as a percentage (%) of inhibition, representing the percentage of free radical scavenging activity. The inhibition percentage was calculated using the following formula (Putri et al., 2020):

where the control absorbance refered to the DPPH solution without the test sample, and the sample absorbance refered to the DPPH solution with the test compound.

The principle of the DPPH method is that antioxidants in the test solution donate hydrogen atoms to DPPH radicals, reducing them to a nonradical form. This reduction causes the purple color of DPPH to fade, as indicated by a decrease in the absorbance at the maximum wavelength (Nizori et al., 2008). The higher the concentration of antioxidants in the sample, the more hydrogen atoms or electrons are donated to DPPH, resulting in a more significant color change from purple to yellow (Rodríguez de Olmos et al., 2022). This color change reflects the energy state of the DPPH radical, which is highly reactive and unstable in its radical form but becomes more stable with lower energy after gaining an electron.

2.3. HPTLC method

The antioxidant activity assay using high-performance thin-layer chromatography (HPTLC) wa sconducted using the following steps:

2.3.1. Sample preparation

Extracts or samples were prepared by dissolving them in a suitable solvent, followed by filtration or centrifugation to remove impurities. The concentration of the sample solution was adjusted to ensure optimal detection.

2.3.2. Chromatographic separation

The prepared sample was applied to an HPTLC plate using an applicator. The plate was then developed in a mobile phase within a controlled chromatographic chamber to achieve proper compound separation. The eluent used as the mobile phase in this study was methanol.

2.3.3. Detection and analysis

After development, the plate was dried and incubated in the dark for 30 minutes. The developed plate was observed under 254 nm ultraviolet (UV) light to identify antioxidant activity. Antioxidant compounds appear as colored spots on the plate.

2.3.4. Data interpretation

Antioxidant activity was quantified by measuring the distance from the baseline of the plate to both the eluent and the tested substances using densitometric analysis. The active compounds’ retention factor (Rf) values were recorded, and the results are compared to standard antioxidants.

2.4. Statistical models

This study utilized two distinct statistical tests to assess antibacterial and antioxidant activities The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to assess the normality of the data distribution within each group, while Levene’s test was employed to evaluate the equality of variances across groups. The Kirby–Bauer method for antibacterial activity was analyzed using the Kruskal–Wallis test, followed by a post-hoc Mann–Whitney test. In contrast, as the results of the antioxidant activity tests indicated that the data met both the normality and homogeneity assumptions, a one-way ANOVA was deemed appropriate for comparing the means among the groups. Following a statistically significant ANOVA result, a Tukey Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) post-hoc test was conducted to identify which specific group means differed significantly.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

This study evaluated the effect of adding L. casei on the antibacterial and antioxidant activities of soy yogurt fermented with B. longum and S. thermophilus. The results showed that the addition of L. casei influenced the soy yogurt’s antibacterial and antioxidant activities, which is consistent with the findings of previous studies.

3.1. Antibacterial activity (Kirby–Bauer disk diffusion method)

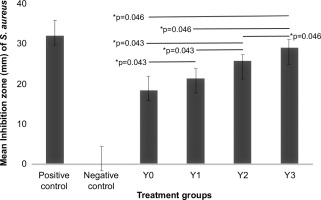

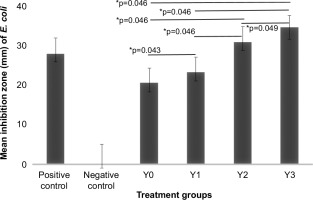

In the Kirby–Bauer method, four samples and a positive control dded to Petri dishes containing two pathogenic bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli). This method was used to measure the potential antibacterial activity of the samples. Table 1 shows the inhibition zone and inhibition power against two bacterial pathogens.

Table 1

Inhibition zone and inhibition factor against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli.

Based on the measurements and classification of the inhibition zones, the gradual addition of L. casei (from Y0 to Y3) increased the antibacterial activity of soy yogurt against both pathogenic bacteria. The Y3 sample, which contained the highest concentration of L. casei, exhibited the largest inhibition zones against S. aureus (29 mm) and E. coli (34.67 mm).

The Kruskal–Wallis test, complemented by the Mann–Whitney post-hoc analysis, demonstrated statistically significant differences in the inhibition zones among the soy yogurt samples when challenged with S. aureus and E. coli. The increasing trend observed within these inhibition zones indicates the potential of L. casei as an antibacterial agent. Heterogeneity in these outcomes may be attributable to a confluence of factors, including variations in fermentation parameters, quantitative and qualitative aspects of the substrates utilized, and synergistic or antagonistic interactions with other bacterial consortia during fermentation. Prior research has indicated that the concentration of L. casei significantly modulates the antibacterial and antioxidant properties, thus underscoring the exigency of optimizing fermentation conditions to attain the predefined target characteristics (Sabil & Amin, 2023).

A previous study on the effect of L. casei levels on the physicochemical and functional properties of date milk found that the addition of L. casei significantly increased the antibacterial activity, pH, and viscosity of the product. This result shows that L. casei improved the functional properties of fermented products. The study indicated that the level of L. casei addition affected the final product, with higher concentrations of bacteria resulting in better functional properties. This is understandable, as the antibacterial activity of L. casei is often associated with lactic acid production, which lowers the pH and increases viscosity (Sabil & Amin, 2023).

3.2. Antioxidant activity

The DPPH and HPTLC methods were applied to three repeatable samples. Tables 2 and 3 show the DPPH and HPTLC calculations for the four soy yogurt samples enhanced with added probiotic bacteria.

Table 2

DPPH results of four soy yogurt samples enhanced with three lactic acid bacteria combinations.

| Sample | Absorption | Inhibition (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Y0 | 0.216 | 41.05 |

| Y1 | 0.204 | 44.55 |

| Y2 | 0.137 | 62.67 |

| Y3 | 0.089 | 75.75 |

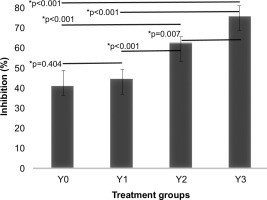

3.3. DPPH method

Table 2 showed that soy yogurt without the addition of L. casei (Y0) had the lowest antioxidant activity, with an inhibition percentage of 41.05%. However, the concentration of L. casei increased in samples Y1 to Y3, and the percentage of free radical inhibition also increased. Here, the Y3 sample, which contained the highest concentration of L. casei, exhibited the highest inhibition percentage at 75.75%. This increase in antioxidant activity indicates that the addition of L. casei tends to enhance the antioxidant capacity of soy yogurt, as shown by the DPPH analysis.

Furthermore, using the ANOVA statistical analysis, the antioxidant test with DPPH methods showed different significance in the percent value of inhibition between the four samples (p-value < 0.05) with an F-statistic of 153.25 and a significance value of 0. Subsequently, a post-hoc Tukey test was conducted, and the results are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 1

Mann–Whitney test results on inhibition zones of Staphylococcus Aureus. Positive control, Clindamycin disc; Negative control, blank disc; Y0, S. thermophilus : B. longum : L. casei = 2:2:0; Y1, S. thermophilus : B. longum : L. casei = 2:2:1; Y2, S. thermophilus : B. longum : L. casei = 2:2:2; and Y3, S. thermophilus : B. longum : L. casei = 2:2:4. *: significant.

Figure 2

Mann–Whitney test results on inhibition zones of Escherichia Coli. Positive control, Clindamycin disc; Negative control, blank disc; Y0, S. thermophilus : B. longum : L. casei = 2:2:0; Y1, S. thermophilus : B. longum : L. casei = 2:2:1; Y2, S. thermophilus : B. longum : L. casei = 2:2:2; and Y3, S. thermophilus : B. longum : L. casei = 2:2:4. *: significant.

Figure 3

Tukey test results on the DPPH method. Y0, S. thermophilus : B. longum : L. casei = 2:2:0; Y1, S. thermophilus : B. longum : L. casei = 2:2:1; Y2, S. thermophilus : B. longum : L. casei = 2:2:2; and Y3, S. thermophilus : B. longum : L. casei = 2:2:4 *: significant.

Figure 3 shows that the p-value for each soy yogurt sample’s mean DPPH absorbance was less than 0.05, except for the Y0–Y1 sample pair. This finding indicates a significant difference between most of the tested soy yogurt samples. The samples Y0–Y3 in this study showed a gradual increase in the inhibitory power of soy yogurt. The consistent increase in the size of inhibition zone indicates the potential of L. casei as an agent to enhance the antioxidant activity in fermented products. This result aligns with a study that demonstrated that addin g L. casei and Zymomonas mobilis to yogurt increased its antioxidant activity. In that study, the inhibition percentage of yogurt with added L. casei reached 98.70%, indicating the strong potential of this bacterium to enhance antioxidant activity. The consistent increase in the inhibition zones highlights the potential of L. casei as an enhancer of antioxidant activity in fermented products (Putro et al., 2020). Another study in 2020 found that soy products fermented with L. casei exhibited higher antioxidant activity (using the DPPH method) than those not fermented with L. casei (Bai et al., 2020).

The present study revealed that the Y3 soy yogurt sample, characterized by a 2:2:4 ratio of B. longum, S. thermophilus, and L. casei, exhibited the highest level of bacterial inhibition compared to other tested samples. These findings align with those of Ziska et al. (2017) regarding probiotic beverages derived from fermented coconut water, demonstrating that fermentation with L. casei enhances antibacterial activity and offers considerable health-promoting potential. This condition corroborates the notion that L. casei, as a probiotic bacterium, not only bolsters antibacterial properties but also contributes to a broader spectrum of health benefits in fermented products (Ziska et al., 2017).

3.4. HPTLC method

Table 3 showed the HPTLC analysis, in which the Rf values of each sample showed that Y2 and Y3 were closer to the Rf value of genistein than those of Y0 and Y1. The Rf values of samples Y2 and Y3 were highly similar to genistein, which was used as the isoflavone standard. Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) densitometry analysis (revealed the Rf values) showed that the tested soy yogurt samples Y2 (0.57) and Y3 (0.59) indicated significant similarity to genistein.

In this study, the Y3 soy yogurt sample, containing LAB in a ratio of S. thermophilus : B. longum : L. casei (2:2:4), had an Rf value closest to the Rf value of the genistein standard solution. The Y3 sample also had the highest inhibition percentage among all tested samples, indicating the highest antioxidant activity. This finding aligns with research that showed that soy fermentation by L. casei and B. lactis increased aglycone levels, including genistein. The antioxidant activity of soy extract in that study increased 2.5 times with the Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity (ORAC) test and 1.6 times with the Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP) test (Genova et al., 2021).

It is known that enzyme β-glucosidase, produced by lactobacilli, convert glucoside isoflavones to bioactive aglycones (Hsiao et al., 2020). Aglycone genistein exhibits various biological activities, including antioxidant and anti-browning activities. It can scavenge free radicals, prevent lipid oxidation, and inhibit the formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) through an RCS trapping mechanism. AGEs are harmful compounds formed by the glycation reaction of proteins with sugars. They are associated with premature aging because of their ability to damage the structure and function of proteins in the body. Based on these studies, the addition of L. casei generally has a positive impact on the antibacterial and antioxidant activities of various fermented products. Previous research has shown that L. casei can improve product quality and functional properties. However, the results vary depending on the type of raw material, bacterial concentration, and fermentation conditions (Song et al., 2021).

Another study in 2020 also found higher levels of daidzein and genistein in soy milk fermented with a combination of L. casei and L. acidophilus than fermented with either bacterium alone. Their study also showed the highest DPPH activity in soy milk fermented with a combination of L. casei and L. acidophilus (Ahsan et al., 2022). Research on the formulation of synbiotic drinks made from milk and sweet potatoes using L. casei showed that the addition of probiotic bacteria improved the product’s physical, microbiological, and antioxidant properties. Their study found that the best composition was achieved by adding 2% L. casei and a 3:1 ratio of milk to sweet potatoes.

This research indicates that the optimal concentration of L. casei used as a fermentative supplement for soybeans is crucial for optimizing the antibacterial and antioxidant activities of soy yogurt. This is supported by research from Aini and Wijonarko in 2018 on the formulation of synbiotic beverages from milk and sweet potatoes using L. casei, which showed that the best composition was achieved with the addition of 2% L. casei and a milk-to-sweet potato volume ratio of 3:1. This suggests that the right combination of raw materials and the concentration of L. casei can influence the functional properties of the product (Mawar et al., 2018).

This study offers significant insights into L. casei’s capacity to augment soy yogurt’s antibacterial and antioxidant properties. These results bolster the understanding that probiotics can offer considerable health advantages and serve as a source of ingredients for creating functional food items. Further research is warranted to identify the ideal concentration and suitable fermentation conditions to optimize the advantages of L. casei in fermented products, such as soy yogurt.

CONCLUSION

Lactobacillus casei significantly enhanced the antibacterial and antioxidant activities of soy yogurt fermented with Bifidobacterium longum and Streptococcus thermophilus. These findings indicate the potential of adding Lactobacillus casei as a probiotic that can be used to inhibit aging and improve health.