1. INTRODUCTION

Phenolic compounds originating from plants are of growing interest because of their wide-ranging bioactivities and potential therapeutic effects (Tungmunnithum et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2022). These bioactive constituents demonstrate notable efficacy in both free radical scavenging and inhibition of microbial growth, making them valuable for applications in food preservation, disease prevention, cosmetics, and pharmaceutical formulations (Kumar et al., 2022). Growing concerns over the safety of synthetic additives, along with the rise in antibiotic-resistant microorganisms, have further emphasized the need for effective and safe natural alternatives (Vaou et al., 2021).

Among plant sources, cashew (Anacardium occidentale) leaves have been highlighted for their abundant phenolic compounds, potent free radical scavenging effects, and promising antimicrobial activity (Gutiérrez-Paz et al., 2024; Leite et al., 2016; Salehi et al., 2020). The properties of cashew leaves indicate their potential as a source of biologically active agents for health-related and functional applications.

Cashew, a tropical evergreen tree belonging to the Anacardiaceae family, is primarily cultivated for its edible nuts and pseudofruits (Gutiérrez-Paz et al., 2024). Young leaves exhibit colors ranging from greenish and brownish to reddish, while mature leaves transition to a dark green hue, typically measuring 10–18 cm in length and 8–15 cm in width. The leaves reach maturity within 20–25 days, with each terminal stem bearing approximately 3–4 leaves (Nkumbula et al., 2023). The leaves are rich in phenolic acids, flavonoids, tannins, and terpenoids, which contribute to their strong antioxidant and antibacterial

properties (Baptista et al., 2018; Fidriany et al., 2012; Onuh et al., 2017; Kurniasari et al., 2024). These bioactive components help to neutralize free radicals, thereby reducing the oxidative stress associated with various chronic diseases (Chaudhary et al., 2023; Pham-Huy et al., 2008). Additionally, their antibacterial activity suggests their potential applications as natural antimicrobial agents (Chabi Sika et al., 2014; Salehi et al., 2020).

Cashew trees exhibit genetic diversity, with varieties that produce either yellow or red fruits. This color variation reflects differences in phytochemical composition, which may affect the bioactive properties of various plant parts, including the leaves (Alhaji Saganuwan, 2018; Bhat and Paliyath, 2016). Terpenoids and flavonoids are phytochemicals that contribute to the yellow coloration of plants, whereas carotenoids are responsible for red and orange colors (Onuh et al., 2017). These color differences indicate the distinct chemical compositions and medicinal properties of the plants (Alhaji Saganuwan, 2018). However, comparative studies examining the phytochemical composition and antioxidant, antibacterial, and antityrosinase properties of yellow- and red-fruited cashew tree leaves are limited. Understanding these variations is essential for identifying optimal plant materials for future applications. Another important factor influencing the bioactivity of cashew leaf extracts is the extraction method used. Different techniques yield extracts with varying levels of bioactive compounds, which affects their antioxidant efficacy. However, no comprehensive studies have been conducted to compare extraction methods for optimizing phenolic and antioxidant yields from cashew leaves.

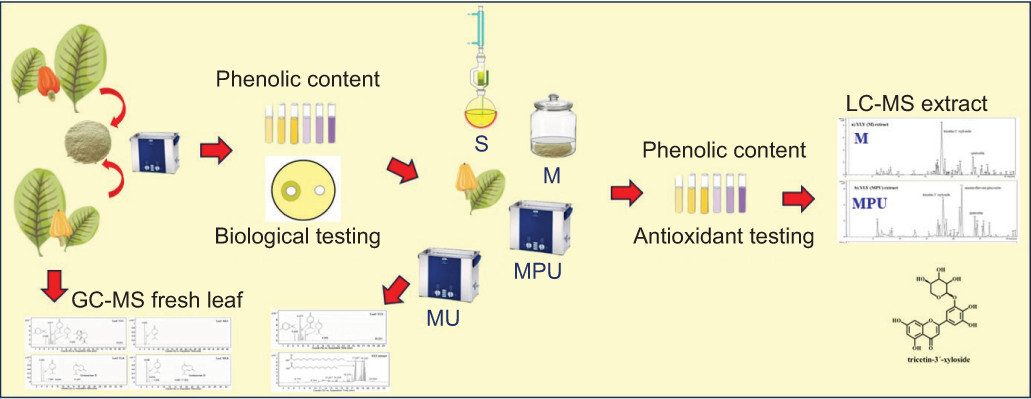

Therefore, this study compared the phytochemical composition and antioxidant, antityrosinase, and antibacterial activities of young and mature leaves from yellow- and red-fruited cashew trees and evaluated the efficacy of different extraction techniques. To provide a comprehensive chemical profile, advanced analytical techniques were employed, including gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) for the analysis of leaf volatile composition and liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) for the characterization of the most active extract. This study reveals a novel relationship between genetic diversity and leaf maturity and their influence on the chemical constituents and biological responses of cashew leaves, thereby identifying the most suitable leaf types for application in the food, pharmaceutical, and cosmetics industries.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Chemicals

Absolute ethanol, gallic acid, kojic acid, sodium carbonate, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), 2,4,6-tris(2-pyridyl)-s-triazine (TPTZ), mushroom tyrosinase, and L-tyrosine were derived from Sigma-Aldrich. 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), ascorbic acid, and 2,2'-azino-bis(3-ethylbenothiazoline-6-sulphonic acid) diammonium salt (ABTS) were obtained from Merck. Folin-Ciocalteu reagent was purchased from Fisher Scientific. Sodium acetate trihydrate and potassium persulfate were acquired from Loba Chemie. Ferric chloride hexahydrate and glacial acetic acid were supplied by QRëC. Mueller-Hinton agar was purchased from HiMedia. Ampicillin and ciprofloxacin discs were derived from Oxoid Ltd.

2.2. Plant material

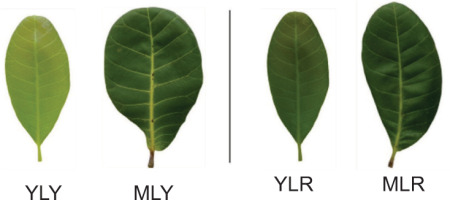

Young and mature leaves from yellow- and red-fruited cashew trees (YLY, MLY, YLR, and MLR, respectively), as shown in Figure 1, were collected from the Chulabhorn district, Nakhon Sri Thammarat province, Thailand, in July 2023.

Plant materials were taxonomically authenticated by a specialist in botany at the Division of Biological Science, Faculty of Science and Digital Innovation, Thaksin University, Thailand. The collected leaves were rinsed with tap water, cut into small segments, and left to dry under ambient conditions for 7 days. Subsequently, the dried material was ground into a fine powder and stored in sealed zip-lock bags at 4°C until use.

2.3. Extraction of four types of cashew leaves

Each leaf powder sample (100 g) was soaked in absolute ethanol at a ratio of 1:4 (w/v) for 5 days at ambient temperature. The mixture was then subjected to ultrasound-assisted extraction at 45 kHz and 40°C for 30 minutes. The extraction mixture was passed through Whatman No. 1 filter paper to remove insoluble matter, and the resulting filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure using a rotary evaporator (Büchi, Germany) at 40°C. All four extracts were immediately transferred into sealed containers and maintained at 4°C.

2.4. Methods for Extraction

The powder of selected leaves (100 g) was subjected to four distinct extraction methods using absolute ethanol at a sample-to-solvent ratio of 1:4 (w/v). The methods employed were as follows: (1) maceration at room temperature for 5 days, (2) maceration for 5 days followed by ultrasound-assisted extraction (45 kHz, 40°C, 30 minutes), (3) maceration for 5 days followed by pulsed ultrasound-assisted extraction (45 kHz, 40°C, 30 minutes), and (4) Soxhlet extraction for 5 hours. After filtration, the solution was concentrated by rotary evaporation under reduced pressure. The extraction yields were calculated as percentages, and the crude extracts were refrigerated at 4°C.

2.5. Determination of Total phenolic content (TPC)

Total phenolics were determined using the Folin-Ciocalteu colorimetric method (Fu et al., 2011). In brief, 60 µL of the extract (1.0 mg/mL in 20% DMSO) was combined with 125 µL of 10% Folin-Ciocalteu reagent and left to react at room temperature for 5 minutes. Then, 100 µL of 7% Na2CO3 solution was added to each well of a 96-well microplate. The mixtures were gently mixed and kept in the dark at room temperature for 15 minutes. The absorbance was recorded at 760 nm using a microplate reader (Bio Chrom/EZ Read 2000). A standard curve prepared from gallic acid solutions (0.01–0.07 mg/mL) was used to calculate the TPC of the samples. The results were reported as milligrams of gallic acid equivalents per gram of dry extract (mg GAE/g).

2.6. Evaluation of antioxidation activity

2.6.1. DPPH radical scavenging activity assay

The DPPH radical scavenging assay was performed based on a modified version of the protocols reported by Vichit and Saewan (2016) and Thepthong et al. (2024), with minor modifications. Briefly, 10 µL of the sample solution (0.0625−1.25 mg/mL) was added to 290 µL of 0.1 mM DPPH solution in a 96-well microplate. After incubation in the dark for 30 minutes, the absorbance at 517 nm was measured using a microplate reader. Ascorbic acid was employed as a standard, and the percentage of DPPH inhibition was calculated as follows:

Acontrol represents the absorbance of DPPH in the absence of the test sample, and Asample represents the absorbance of DPPH in the presence of the test sample.

The concentration of each sample required to inhibit 50% of the DPPH radicals (IC50) was estimated by plotting the inhibition percentages against the sample concentrations, followed by linear regression analysis.

2.6.2. ABTS radical scavenging assay

The ABTS radical scavenging activity was evaluated according to a slightly modified method described by Re et al. (1999) and Xiao et al. (2020). A stock solution of ABTS•+ was generated by adding a 2.45 mM potassium persulfate solution to a 7 mM ABTS solution at a 1:2 volume ratio. After incubation in the dark for 16 hours, the formed ABTS•+ solution was adjusted with ethanol to attain an absorbance of 0.70 ± 0.02 at a wavelength of 734 nm. For the assay, 25 µL of the sample solution (0.0625-1.25 mg/mL) was combined with 225 µL of ABTS•+ solution in each well of a 96-well plate. After 15 minutes of incubation in the dark, the absorbance of the reaction mixture was measured at 734 nm using a microplate reader. Ascorbic acid was used as the standard antioxidant. The percentage of ABTS•+ radical scavenging activity was determined using the following equation:

Acontrol refers to the absorbance of ABTS•+ in the absence of the test sample, and Asample refers to the absorbance of ABTS•+ in the presence of the test sample. The IC50 values were determined using the same method employed in the DPPH assay.

2.6.3. Ferric-reducing antioxidant power assay

The ferric-reducing antioxidant power of the cashew leaf extract was determined according to the protocol described by Thepthong and coworkers (Thepthong et al., 2024) with slight modifications. The FRAP reagent was prepared by combining 10 mM TPTZ, 20 mM ferric chloride, and 0.3 M acetate buffer (pH 3.6) in a 1:1:10 ratio, respectively. For the assay, 50 µL of the sample solution (1.0 mg/mL) was mixed with 150 µL of FRAP reagent in a 96-well plate. The mixture was kept in the dark for 5 minutes at ambient temperature. Absorbance was recorded at 593 nm using a microplate reader. The FRAP values of the extracts were quantified using a standard calibration curve of ascorbic acid (0.0625–1.0 mg/mL). The results are represented as ascorbic acid equivalents in milligrams per gram of extract (mg AAE/g extract).

2.7. Evaluation of antityrosinase activity

The tyrosinase inhibitory activity of the cashew leaf extracts was determined according to the method described by Thepthong et al. (2024) with some modifications. The tyrosinase inhibition assay was conducted using mushroom tyrosinase and L-tyrosine as the enzyme and substrate, respectively. The reaction mixture consisted of 40 µL of a 1.7 mM L-tyrosine solution prepared in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 6.8) and 40 µL of the extract. The mixture was kept at room temperature for 15 minutes to allow interaction between the substrate and sample. Subsequently, 40 µL of mushroom tyrosinase enzyme solution (500 U/mL in phosphate buffer) was introduced to initiate the enzymatic reaction. The reaction was allowed to proceed at room temperature for 25 minutes. The formation of dopachrome was quantitatively assessed by measuring the absorbance at 490 nm with a microplate spectrophotometer. Kojic acid served as the standard substance. The inhibitory activity against tyrosinase was determined and expressed as the percentage of enzyme inhibition, calculated according to the following equation:

where Acontrol is the absorbance of dopachrome in the absence of the extract, and Asample is the absorbance in the presence of the extract. The IC50 values were determined following the same procedure employed in the DPPH radical scavenging assay.

2.8. Antibacterial activity assay

Two reference bacterial strains, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923 (a gram-positive bacterium) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853 (a gram-negative bacterium), were revived from frozen glycerol stocks and subcultured on Mueller-Hinton agar (MHA) plates. Incubation of the bacterial strains was carried out at 37°C for 18–24 hours under aerobic conditions to ensure optimal microbial growth. Isolated colonies from fresh cultures were suspended in sterile 0.85% saline solution. The bacterial suspension was adjusted to a turbidity equivalent to the 0.5 McFarland standard, corresponding to approximately 1.5 × 108 CFU/mL, and used in the antibacterial assay.

The antibacterial activity of cashew leaf extracts was evaluated using a modified agar well diffusion method, as described by Balouiri et al. (2016) and Thepthong et al. (2023). Standardized suspensions of S. aureus and P. aeruginosa in 0.85% saline were spread on Mueller-Hinton agar plates in three directions, rotating 60° each time to ensure an even distribution. Wells (6 mm diameter) were created and filled with 60 µL of extract at various concentrations. The plates were then incubated at 37°C under aerobic conditions for 18–24 hours. The diameters of the inhibition zones were measured using a digital caliper, with clear zones indicating antibacterial activity. Standard antibiotic discs (ampicillin for S. aureus and ciprofloxacin for P. aeruginosa) served as positive controls, and absolute ethanol served as a negative control. Each experiment was conducted in triplicate, and the antibacterial activity was reported as the mean diameter of the inhibition zones. Antibacterial activity was classified as resistant (≤12 mm), intermediate (13-16 mm), or susceptible (≥17 mm) according to the CLSI guidelines (2020).

2.9. GC-MS analysis

Volatile compounds in both fresh cashew leaves and the YLY extract were characterized by GC-MS, following the protocol established by Thepthong et al. (2023), with some modifications. The analysis was carried out on an Agilent 7890B gas chromatograph coupled to a 5977 Series mass spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, USA). Separation was carried out on an HP-5MS capillary column (30 m × 250 µm i.d., 0.25 µm film thickness). The temperature of the GC oven was initially set at 60°C for 3 minutes, increased at a rate of 4°C/minute to 220°C, and finally held at the final temperature for 5 minutes. The injector temperature was maintained at 250°C. A constant flow of helium at 1 mL/minute was employed as the carrier gas. The injection was performed in splitless mode using a 1 µL sample volume.

The mass spectrometer was operated in electron impact (EI) mode with an ionization energy of 70 eV. The ion source and interface temperatures were set to 250°C. Mass spectra were collected over an m/z range of 5–600. Compound identification was carried out by matching the obtained spectra against entries in the NIST Mass Spectral Library (version 1.4; National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD, USA). Only compounds with a spectral similarity score exceeding 80% were reported.

2.10. LC-MS analysis

Phytochemical profiling of the extract was conducted using a LC-MS system comprising a Thermo Fisher Scientific Ultimate 3000 UHPLC unit coupled to a Bruker microTOF-Q II mass spectrometer. Chromatographic separation was achieved using a Zorbax SB-C18 StableBond Analytical column (4.6 × 250 mm, 3.5 μm particle size) with a binary mobile phase consisting of 0.1% formic acid in water (solvent A) and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (solvent B). The gradient elution program was set as follows: 0–5 minutes, 20% B; 5–40 minutes, linear increase from 20% to 100% B; 40–45 minutes, maintained at 100% B; 45–47 minutes, decreased from 100% to 20%B; and 47–60 minutes, held at 20% B for column re-equilibration. The flow rate was consistently maintained at 0.4 mL/minute during the analysis. Mass spectrometric detection was performed using electrospray ionization in the negative ion mode, with a scan range of m/z 50–1500. The MS parameters included a capillary voltage of 4500 V, drying gas flow rate of 8.0 L/minute at 180°C, and a nebulizing gas pressure of 2.0 bar.

2.11. Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate, and the results are reported as the mean values accompanied by their respective standard deviations (SD). Statistical analyses were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) via the SPSS software package for Windows. To evaluate significant differences among group means, Tukey’s post hoc test was applied, with statistical significance set at p < 0.05.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

3.1. The Yield of four cashew leaf extracts

The extraction yields of the four cashew leaves are presented in Table 1. Young yellow-fruited leaves (YLY) exhibited the highest yield (7.42%), followed by mature yellow-fruited leaves (MLY). In contrast, red-fruited leaves, both young (YLR) and mature (MLR), showed lower yields than yellow-fruited leaves. Specifically, the yield of YLY was approximately 53% higher than that of YLR, and MLY was 31% higher than MLR. These results suggest that yellow-fruited cashew varieties may contain higher levels of extractable constituents, potentially reflecting genetic differences associated with fruit color that influence the quantity or type of chemical constituents in the leaves. This is the first report on the comparative extraction yields of cashew leaves from trees bearing fruits of different colors and with varying maturities of leaves.

Table 1

Percentage yield and total phenolic content of the four cashew leaf extracts.

| Samples | Percentage yield (w/w dry weight) | Total phenolic content (mg GAE/g extract) |

|---|---|---|

| YLY | 7.42 | 220.79 ± 3.22a |

| MLY | 5.43 | 194.41 ± 2.63a |

| YLR | 4.84 | 125.80 ± 6.04b |

| MLR | 4.15 | 78.01 ± 4.37c |

| Ascorbic acid | - | - |

The higher yield observed in young leaves can be attributed to their higher concentrations of ethanol-soluble phytochemicals, such as phenolics and flavonoids, and their more permeable cellular structures, which enhance the solvent penetration and extraction efficiency (Thi and Hwang, 2014). Similar age-dependent trends have been reported for Moringa oleifera, where younger leaves exhibited higher phenolic content and antioxidant activity than older leaves (Nobossé et al., 2018).

The TPC of the four crude extracts varied between 78.01 ± 4.37 and 220.79 ± 4.5 mg GAE/g extract, as summarized in Table 1. The highest phenolic content was observed in young leaves from yellow-fruited trees (YLY), suggesting that this variety is a rich source of phenolic compounds, likely due to enhanced metabolic activity and secondary metabolite biosynthesis during the early stages of leaf development. However, mature leaves from the same variety (MLY) exhibited lower TPC than those from YLY. Significant differences were also observed between the fruit-color varieties. Young leaves from red-fruited trees (YLR) had a slightly lower TPC than YLY, indicating that genetic variation influences phenolic biosynthesis. Mature leaves from red-fruited trees (MLR) exhibited the lowest TPC, supporting the trend of a decrease in phenolic content with increasing leaf maturity. This result is higher than that reported by Onuh et al. (2017), who observed a TPC of 103.92 mg/g methanol extract. The higher values may be influenced by differences in the extraction methodology, including solvent polarity, as well as the physiological age of the leaf material used.

3.2. Antioxidant activities of four cashew leaves

The antioxidant activities of the four cashew leaf extracts, evaluated using DPPH, ABTS, and FRAP assays, are presented in Table 2. Among the tested samples, the young yellow-fruited leaf extract (YLY) demonstrated the most potent antioxidant performance in all three assays, with IC50 values of 9.05 ± 0.41 µg/mL (DPPH) and 11.70 ± 1.28 µg/mL (ABTS), and the highest FRAP value of 339.71 ± 5.29 mg AAE/g extract. The DPPH scavenging activity of YLY was slightly higher than that of the ethanolic extract previously reported by Jaiswal et al. (2010), which had an IC50 of 9.41 μg/mL.

Table 2

Antioxidant activities of the four cashew leaf extracts.

In contrast, the mature red-fruited leaf extract (MLR) showed the weakest activity, with significantly higher IC50 values in both radical scavenging assays (20.40 ± 0.08 µg/mL for DPPH and 28.06 ± 2.58 µg/mL for ABTS) and the lowest FRAP value (249.84 ± 6.53 mg AAE/g extract). This decreasing trend in antioxidant capacity from young to mature leaves and yellow- to red-fruited varieties was consistent across the three assay methods.

The superior antioxidant activity observed in YLY can be attributed to its higher levels of ethanol-soluble phenolic constituents or phenolic acids, which are known to contribute to its free radical scavenging and electron-donating capabilities. These results support a previous report that younger leaves tend to possess greater antioxidant potential than mature leaves, likely due to developmental variations in secondary metabolite accumulation (Thi and Hwang, 2014). Additionally, the superior performance of yellow-fruited varieties over red-fruited varieties suggests that fruit color may reflect the underlying genetic factors influencing phenolic biosynthesis and could serve as a visual marker for antioxidant potential in cashew leaves.

3.3. Antityrosinase and antibacterial activity of four cashew leaves

The cashew leaf extract exhibited weak antityrosinase activity, with IC50 values ranging from 316.02 to 356.02 μg/mL, as shown in Table 3. Their effectiveness was notably weaker than that of the positive control, kojic acid (IC50 = 44.24 ± 3.12 μg/mL). The young yellow-fruited leaves (YLY) exhibited the strongest inhibitory effect, with an IC50 value of 316.02 ± 11.00 μg/mL (69.52% inhibition), followed closely by mature yellow-fruited leaves (MLY) and both young and mature red-fruited leaves (YLR and MLR). Although slight variations were noted, the tyrosinase inhibitory activities among the cashew leaf extracts did not differ significantly. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to report comparable levels of tyrosinase inhibition across cashew leaf extracts derived from different developmental stages and fruit color variants.

Table 3

Antityrosinase and antibacterial activities of cashew leaf extracts.

The antibacterial efficacy of the four cashew leaf extracts was evaluated against S. aureus and P. aeruginosa. All extracts demonstrated measurable inhibition, with zones ranging from 12.0-17.0 mm for S. aureus and 12.0-16.5 mm for P. aeruginosa (Table 3). The extract derived from young yellow-fruited leaves (YLY) exhibited the most potent activity against both bacterial strains (17.0 ± 1.00 mm and 16.5 ± 0.50 mm, respectively), which correlated with their elevated TPC and the presence of bioactive compounds such as terpenes. Extracts from mature leaves (MLY and MLR) showed reduced activity, particularly against P. aeruginosa, likely due to a decrease in phenolic content during leaf maturation. Although red-fruited varieties (YLR and MLR) contained distinctive volatiles, such as germacrene D (as determined by GC-MS), their antibacterial effects were not superior, indicating the limited efficacy of these compounds. The standard antibiotics, ampicillin and ciprofloxacin, produced zones of inhibition three times larger than those produced by the extracts. Nonetheless, the extracts demonstrated broad-spectrum antibacterial activity, and the significant differences (p < 0.05) among the treatments highlighted the influence of fruit color and leaf developmental stage. These results suggest that young yellow-fruited cashew leaves are promising natural sources of antibacterial agents.

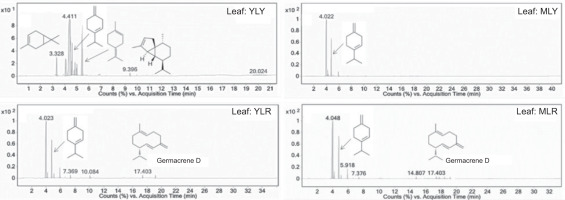

3.4. Volatile compounds in four cashew leaves

The GC-MS chromatograms revealed distinct chemical profiles among the four fresh cashew leaves, providing valuable insights into how leaf maturity and fruit variety influence the composition of volatile components in the leaves. The chromatogram of fresh YLY leaves displayed the most complex profile, with multiple peaks at retention times of 3.3–5.5, 9.396, and 20.024 minutes (Figure 2). These peaks correspond to volatile compounds that were more intense than those in the other samples. Structural analysis identified these compounds as terpenes, including 3-carene, β-terpinene, 1-methyl-4-(1-methylethylidene)cyclohexene, and α-cubebene, with retention times of 3.328, 4.792, 5.343, and 9.396 minutes, respectively.

These terpenes are associated with various biological activities, particularly antimicrobial and antioxidant properties. Notably, all of these compounds feature allylic protons that act as hydrogen donors, which may contribute to the potent scavenging activity observed in YLY leaves. In contrast, the MLY chromatogram displayed fewer peaks, with β-terpinene as the key volatile component at a retention time of 4.792 minutes. This substantial difference between YLY and MLY confirms that leaf maturity affects the chemical composition, with young leaves retaining higher concentrations of volatile compounds.

The GC-MS chromatogram of YLR revealed distinctive peaks at 7.369, 10.084, and 17.403 minutes. The peak at 17.403 minutes was identified as germacrene D, a sesquiterpene commonly found in plant essential oils with antimicrobial properties. Similarly, the MLR chromatogram showed peaks at 5.918, 7.376, 14.807, and 17.403 minutes (corresponding to germacrene D). The presence of germacrene D in both red-fruited varieties (YLR and MLR) and its absence in yellow-fruited varieties (YLY and MLY) indicates a genotype-specific biosynthetic pathway that is potentially linked to the production of red pigments in cashew fruits. The volatile compound profile of the fresh leaves differed from that of the extract reported by Maia et al. (2000).

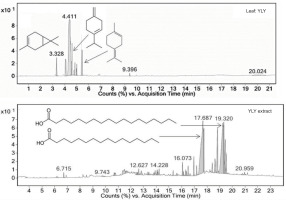

GC-MS analysis of YLY leaves and their ethanol extract revealed distinct phytochemical profiles, as shown in Figure 3. The raw leaf chromatogram displayed prominent early eluting peaks at retention times of 3.328, 4.792, and 5.343 minutes, which were identified as 3-carene, β-terpinene, and 1-methyl-4-(1-methylethylidene)cyclohexene, respectively. The results indicated an abundance of volatile monoterpenes. In contrast, the ethanol extract exhibited major peaks at retention times of 17.687 and 19.320 minutes, corresponding to n-hexadecanoic acid and n-octadecanoic acid, respectively, demonstrating the successful concentration of less volatile, higher molecular weight compounds. This transformation in chemical composition during extraction highlights the effectiveness of ethanol in selectively concentrating bioactive components with potentially stronger antioxidant properties while reducing the amount of volatile compounds. According to these results, the young leaves of yellow-fruited trees were selected as the optimal plant material for further investigation. Interestingly, the volatile compounds in the extract were different from those reported by Maia et al. (2000).

3.5. Yield of the four extraction methods

The extraction yields from the young leaves of yellow-fruited trees were determined using four methods, as illustrated in Table 4. Pulsed ultrasound-assisted maceration (MPU) produced the highest yield (7.91%), followed closely by ultrasound-assisted maceration (MU) at 7.58%. Conventional maceration (M) yielded 6.28%, whereas Soxhlet extraction (S) resulted in the lowest yield. The superiority of maceration followed by pulsed ultrasound-assisted extraction (MPU, 7.91% yield) over other methods demonstrates the effectiveness of the combined extraction techniques. The observed increase in extraction efficiency can be attributed to the cavitation effect of the ultrasonic waves, which improves solvent penetration and mass transfer in plant tissues (More and Arya, 2021; Pan et al., 2012).

Table 4

Percentage yield, total phenolic content, and DPPH scavenging activity of cashew leaf extracts from four extraction methods.

This result is consistent with that of Hiranpradith et al. (2025), who reported an increase in yield using ultrasound-assisted methods compared with conventional techniques.

3.6. TPC and DPPH scavenging activity of four extracts obtained by different methods

The extraction method had a significant influence on the TPC of the cashew leaf extracts (Table 4). Maceration combined with pulsed ultrasound-assisted extraction (MPU) yielded the highest TPC (206.67 ± 14.24 mg GAE/g extract), which was not significantly different from that obtained using maceration combined with ultrasound-assisted extraction (MU). The phenolic content was higher than that reported by Kurniasari et al. (2024), who found 115.76 ± 0.262 mg GAE/g ethanol extract. Soxhlet extraction (S) resulted in a lower TPC than ultrasound-assisted methods, whereas conventional maceration (M) yielded the lowest TPC, which was significantly lower than that achieved with both ultrasound-assisted techniques.

These results suggest that the application of ultrasound energy, particularly pulsed ultrasound, significantly enhanced the extraction efficiency of phenolic compounds from cashew leaves. This enhancement can be attributed to the cavitation phenomenon induced by ultrasound, which creates microjets and shockwaves that disrupt plant cell walls, facilitating the release of intracellular contents and improving the mass transfer rates. Furthermore, the comparable results of pulsed (MPU) and continuous (MU) ultrasound applications indicate that both methods are effective, with a slight advantage for pulsed ultrasound, possibly because of the reduced thermal degradation of heat-sensitive phenolic compounds during the extraction process. These findings align with those of previous studies by Pan et al. (2012), who reported an increase in phenolic compound extraction when using pulsed ultrasound-assisted methods in medicinal plants.

The DPPH radical scavenging activity of cashew leaf extracts varied significantly across the different extraction methods (Table 4). The extract obtained using the MPU method exhibited the strongest antioxidant activity, with an IC50 value of 14.04 ± 0.07 μg/mL, closely followed by the extract obtained using the MU method (14.60 ± 0.14 μg/mL). The Soxhlet (S) method extract demonstrated lower activity (15.44 ± 0.15 μg/mL), which was not significantly different from that of the ultrasound-assisted methods. However, the extract obtained using the conventional maceration (M) method showed substantially weaker activity, with an IC50 value of 22.81 ± 0.41 μg/mL, which was significantly lower than those obtained using all other extraction methods. All the extraction methods produced extracts with antioxidant activity, but none exhibited greater potency than the standard ascorbic acid. The superior DPPH radical scavenging activity observed in ultrasound-assisted extraction correlated well with the higher TPC, supporting the established relationship between phenolic compounds and antioxidant properties (Pan et al., 2012).

3.7. Phytochemical profiling of YLY extracts via LC-MS/MS

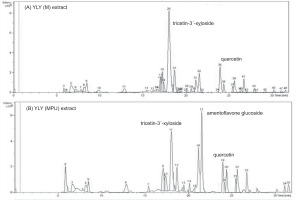

YLY extracts obtained through maceration followed by pulsed ultrasound-assisted extraction (MPU) were analyzed for their major constituents using LC-MS/MS in negative ionization mode and compared with those extracted by maceration (M). The chromatographic profiles are shown in Figure 4, with compound identities confirmed by retention times, molecular formulas, and mass-to-charge ratios (m/z) listed in Table 5.

Table 5

Chemical composition of the YLY extract.

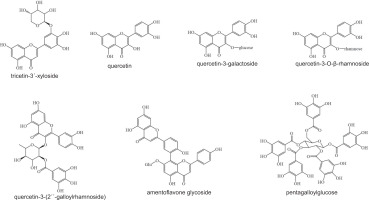

In the maceration extract (Figure 4a), tricetin-3'-xyloside was identified as the predominant compound (RT 18.0 minutes), accompanied by quercetin, quercetin 3-O-β-rhamnoside, quercetin-3-(2''-galloyrhamnoside), and pentagalloylglucose. The extract obtained via maceration with pulsed ultrasound (Figure 4b) similarly featured tricetin 3'-xyloside, along with amentoflavone glucoside (RT 21.5 minutes, as a significant constituent) and quercetin (RT 23.9 minutes). The structural representations of the key compounds are shown in Figure 5.

Profiling revealed the presence of numerous bioactive flavonoids and polyphenols with antioxidant and antibacterial properties. Tricetin-3'-xyloside and quercetin derivatives, common to both extraction methods, are known for their potent antioxidant effects via radical scavenging, metal chelation, and enhancement of endogenous defense mechanisms (Chobot et al., 2020). The presence of glycosylated flavonoids may enhance their solubility and bioavailability, without compromising their activity. Notably, amentoflavone glucoside was detected exclusively in the ultrasound-assisted extract, highlighting the ability of this technique to access compounds that are otherwise difficult to extract. Ultrasound enhances extraction efficiency by disrupting plant cell walls (Xue and Li, 2023), thereby facilitating the release of amentoflavone glucoside and pentagalloylglucose, which contribute to both the antioxidant and antimicrobial properties. These mechanisms include hydrogen donation, protein complexation, enzyme inhibition, and membrane disruption (Masota et al., 2022). Pentagalloylglucose is likely responsible for its strong ferric-reducing power and antibacterial efficacy.

This study demonstrates that the extract from young leaves of the yellow-fruited cashew variety (YLY), which exhibited the highest potential, contains a diverse range of phytochemicals with both antioxidant and antimicrobial activities. The variations in the chemical composition obtained through different extraction techniques highlight the importance of selecting an appropriate method to maximize the recovery of bioactive compounds. These findings support the traditional medicinal use of YLY and highlight its potential as a natural source of pharmacologically active compounds. Nevertheless, further studies on its mechanisms of action and in vivo efficacy are necessary to validate their suitability for pharmaceutical development.

4. CONCLUSION

This study investigated the phytochemical composition and biological activity of cashew leaves from yellow- and red-fruited trees at different maturity stages. Young leaves from yellow-fruited trees had higher levels of phenolic compounds and exhibited more potent antioxidant, antityrosinase, and antibacterial activities than mature leaves and red-fruited varieties. Pulsed ultrasound-assisted extraction improved both the extraction yield and recovery of bioactive constituents. Chemical analysis identified tricetin 3'-xyloside and quercetin derivatives as the major components of the crude extracts. Different extraction methods produced distinct phytochemical profiles, with ultrasound techniques enabling the isolation of compounds such as amentoflavone glucoside, which were not recovered by conventional methods. These results support the traditional medicinal use of cashew leaves and highlight their potential as sustainable sources of natural antioxidants and antimicrobial agents. Varietal- and maturity-dependent differences in phytochemical content provide useful information for optimizing the harvesting and processing of cashew leaves for food and nutraceutical applications.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support provided by the Research Equipment Center, Thaksin University, Thailand. We also extend our appreciation to the Division of Biological Science, Faculty of Science and Digital Innovation, Thaksin University, for providing the bacterial testing resources.