1. INTRODUCTION

Glioma refers to a broad category of primary brain tumors, including astrocytic tumors (including glioblastoma, astrocytoma, and anaplastic astrocytoma), oligodendroglioma, ependymoma, and mixed glioma (Agnihotri et al., 2013). World Health Organization (WHO) categorizes gliomas into four classes based on their malignancy level and histopathological characteristics. Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is included in the stage IV glioma class, which is known for its very aggressive nature and its tendency to infiltrate surrounding healthy tissue (Ostrom et al., 2018). Histologically, GBM tumors exhibit active mitotic division and show signs of proliferation and microvascular necrosis (Lee et al., 2021). GBM arises from glial cells in the brain and is a common and deadly variant of malignant brain tumor, accounting for more than 60% of cases in the central nervous system worldwide (Rock et al., 2012).

GBM is most influenced by developmental mechanisms of genes involved in the cellular regulation activities, namely apoptosis, cell division, motility, and angiogenesis (Shah and Sukumar, 2010). During embryogenesis, HOX genes serve as regulatory transcription factors; the Homeobox (HOX) family has a significant function in the spread and growth of the tumor and cancer development (Bhatlekar et al., 2014). In cervical cancer, HOXA5 has been implicated in influencing tumor cell invasion and proliferation (Ma et al., 2020). The HOXC9 gene expression is linked to the organization of different malignant tumors, for example, colorectal cancer (Hu et al., 2019). Similarly, HOXC10 expression has been linked to promoting proliferation, migration, and invasion in gliomas (Li et al., 2018). In contrast to HOXA5, HOXC9, and HOXC10, which contribute to tumor progression by enhancing proliferation, HOXB1 expression functions as a suppressor of tumor growth in GBM, reducing cell viability and promoting apoptosis (Han et al., 2015). Targeting the regulation of HOX gene expression represents a potential therapeutic approach for GBM treatment.

The diagnosis of GBM is established through histopathological examination of tumor cells, which exhibit characteristics such as high mitotic activity, microvascular proliferation, and necrosis (Kiesel et al., 2018). The excessive mitotic activity and proliferation observed are a result of disrupted apoptotic mechanisms, leading to uncontrolled cell division. Furthermore, this process can cause additional damage to the surrounding tissue, impeding the healing process. Therefore, regulating apoptosis and necrosis represents a potential strategy for GBM treatment, but cell necrosis, characterized by loss of membrane integrity, triggers an inflammatory response in the surrounding tissue, aiming to eliminate dead cells through phagocytosis.

Nevertheless, these approaches have only led to a modest 7.2% increase in the average survival rate for patients. At present, GBM therapy primarily involves a combination of surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and supportive care (Bach, 2021). GBM causes progressive neurological decline in affected individuals (Tan et al., 2020). GBM treatment with a standard approach involves adjuvant temozolomide (TMZ) therapy, which begins with surgical extraction of the tumor (Hanif et al., 2017). The N7 and O6 positions of TMZ-treated guanine have a cytotoxic effect, O6-methylguanine induces mismatches that trigger futile mismatch-repair cycles, leading to DNA damage accumulation and apoptosis. Therefore, the cell cycle progression that is present in the G2-M checkpoint is disrupted, resulting in cells starting to die in a programmed manner, known as apoptosis (Scott et al., 2011). Nevertheless, TMZ therapy in GBM treatment has limitations, including high cost and the occurrence of numerous side effects (Sengupta et al., 2012). Thus, improved therapeutic approaches with minimal side effects to enhance GBM treatment options are needed.

Extract from turmeric rhizomes (Curcuma longa L.), in the form of curcumin, has been used for centuries in traditional medicine in Asian cultures (Kocaadam and Sanlier, 2017). Curcumin and its analogs (demethoxycurcumin and bis-demethoxycurcumin) contain reactive functional groups, including a phenolic groups and 1,3-diketone moiety (Indira, 2013). Due to its intricate and distinctive chemical structure, curcumin has the ability to target various signaling pathways at the molecular level, making it a promising therapeutic agent for diverse diseases (Paulraj et al., 2019). Curcumin has been proven to function as an additional GBM treatment, as supported by previous studies (Hatcher et al., 2008; Ravindran et al., 2009). However, the performance of curcumin compounds in GBM treatment is restricted because of their inadequate targeting of tumor cells, primarily attributed to the inherent properties of natural compounds. Curcumin exhibits low solubility in water, particularly under acidic and neutral conditions, and it is chemically unstable, particularly under neutral and alkaline conditions. In addition, in its role in the human body and exhibiting limited bioavailability, curcumin can quickly act on enzymes for metabolism (Zheng and McClements, 2020). The advent of nanotechnology has paved the way for nanoscale formulation of curcumin, enabling enhanced drug delivery effectiveness in GBM. This approach overcomes biochemical and biophysical barriers, facilitating precise and efficient interactions of the compound with tumor target cells. Consequently, the impact of nanocurcumin on apoptosis and HOX expression in human glioblastoma U87 cells was investigated.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

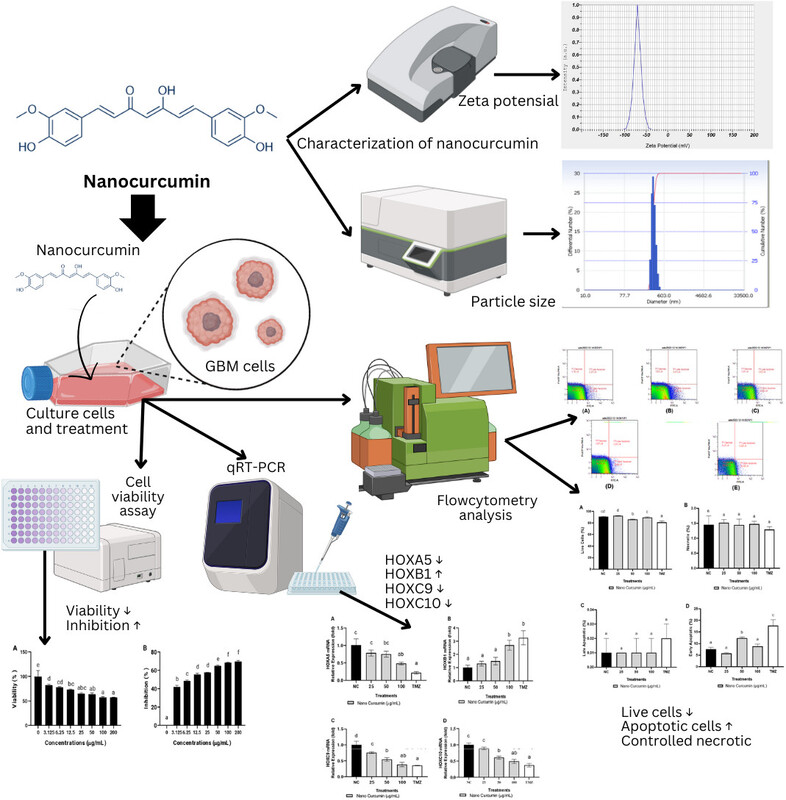

2.1. Nanocurcumin preparation

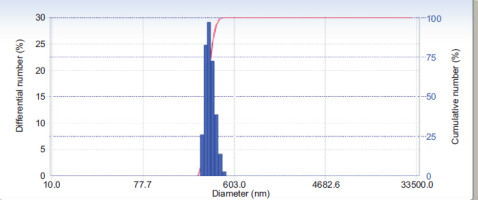

The curcumin utilized was supplied by Plamed Green Science Limited, China. Nanocurcumin was formulated by diluting curcumin with chitosan–sodium tripolyphosphate and characterized following the approach outlined in the preceding study’s methodology (Sandhiutami et al., 2021). The nanocurcumin particles exhibited a size range of 11.5–30.6 nm. For experimental purposes, the nanocurcumin was further diluted in 100% DMSO, resulting in a final concentration containing 1% DMSO.

2.2. Characterization of nanocurcumin

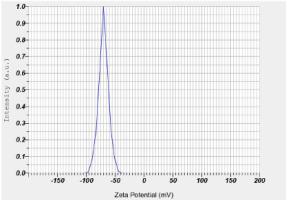

The zeta potential and particles’ size were determined using a dynamic light scattering particle size analyzer (Horiba SZ-100). The sample container was then filled with a cleaned cuvette that held around 1 mL of the material for analysis (Utami et al., 2023).

2.3. Cell culture

Cells were grown in RPMI 1640 medium from Biowest (L0500-500) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum during culture from Biowest (S181B-500), 1% antibiotic-antimycotic from Biowest (L0010-100), 0.1% gentamicin from Gibco (12750060), amphotericin B from Biowest (L0009-050), and vitamin MEM 100x from Biowest (X0556-100). These cells are U87 cells (ATCC HTB-14) were supplied by Aretha Medika Utama, Indonesia. The maximum density was obtained from cultures incubated at 37 °C in a controlled 5% CO2 environment. The cells were then detached using trypsinization, harvested, and subsequently used for the experimental procedures (Widowati et al., 2019; Faried et al., 2021).

2.4. Cells viability assay

A total of 5 × 103 cells were placed in a 96-well plate, then incubated for 24 hours for cell viability testing using the Cell Counting Test Kit (CCK)/WST-8 (Elabscience, E-CK-A362). Fresh medium 180 μL and nanocurcumin 20 μL were substituted for the existing medium at assorted intensities (200, 100, 50, 25, 12.5, 6.25, 3.125, 0 μg/mL) and supplemented into each well. The obtained cells were then subjected to further incubation for an additional 24 hours. Then, incubation was carried out for 3 hours in each well that had been filled with 10 μL of WST-8 reagent. The absorbance of the samples was quantified at a wavelength of 450 nm (Cai et al., 2019). The calculations were performed using the equations below the cell survival rate and inhibition rate.

An OD sample is a sample optical density figure from a cell. OD blank as a negative control, which does not contain cells. Then OD control as a positive control, which was not treated.

2.5. mRNA relative expression measurement

The cells were exposed to the specified concentrations of nanocurcumin (100, 50, and 25 μg/mL) and temozolomide (TMZ) 300 μM. The relative mRNA expressions of HOXA5, HOXB1, HOXC9, and HOXC10 (Table 1) were quantified using the qRT-PCR method. RNA extraction was obtained through using the Direct-zol RNA Miniprep Plus Kit (Zymo, R2073). Subsequently, RNA was isolated for cDNA synthesis with iScript Reverse Transcription Supermix from Bio-Rad (170-8841) based on the instructions provided by the manufacturer. Then, the resulting cDNA was combined with primers (Macrogen), SsoFast Evagreen Supermix from Bio-Rad (172-5200), and nuclease-free water (Zymo, R2073) following the protocol from the manufacturer (Hidayat et al., 2016; Pujimulyani et al., 2020). RNA purity and sample concentration are shown in Table 2.

Table 1

Primer’s information.

2.6. The quantification of apoptotic, live, and necrotic cells

Flow cytometry analysis was used to measure necrotic, viable, and apoptotic cells. Cells 2.5 × 105 were seeded in 6-well plates and cultivated for 24 hours. The cells were then administered with the extract and TMZ and incubated for 24 hours. Harvested cells were rinsed for clearing using 500 μL of FACS buffer and prepared for pelleting using the Annexin V-FITC/PI Apoptosis Detection Kit from Elabscience (E-CK-A211). Cell measurements were carried out using MACSQuant 10 flow cytometry (Miltenyi) (Widowati et al., 2019; Girsang et al., 2021).

2.7. Statistical analysis

Data obtained from three repetitions were tested for normality for analysis. For normally distributed data, analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed. Then, Tukey’s post hoc test was carried out for homogeneous data, while for inhomogeneous data, Dunnett’s T3 post hoc test was performed. The Kruskal-Wallis test was performed for abnormal data, followed by the Mann-Whitney U test. Statistical significance was determined for all observed differences with p-values below 0.05 (Widowati et al., 2022).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Zeta Potential Measurement and Particle Size Analyzer (PSA) of Nanocurcumin

Zeta potential with five repetitions is shown in Table 3. The zeta potential of curcumin nanoparticles was −70.40 ± 3.53 mV (Figure 1). The particle size examination using the PSA tool was also performed with five repetitions, and the results are displayed in Table 4. The overall average size of the nanoparticles, calculated from these five measurements, was 275.88 ± 53.84 nm (Figure 2).

Table 3

Zeta potential of nanocurcumin.

| Repetition | Zeta potential (mV) |

|---|---|

| 1 | –70.1 |

| 2 | –67.5 |

| 3 | –68.9 |

| 4 | –76.5 |

| 5 | –69.0 |

| Average | –70.40 ± 3.53 |

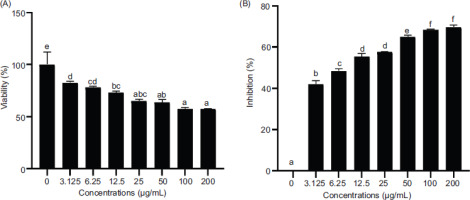

3.2. Inhibition assay of U87 cells by nanocurcumin in dose dependent

In this study, the inhibitory contribution of nanocurcumin on the growth of U87 cells was investigated in a concentration-dependent manner. The WST-8 test was conducted to identify the optimal concentration of nanocurcumin. The results confirmed the presence of a correlation between the concentration of nanocurcumin and cell viability. Higher concentrations of nanocurcumin resulted in lower cell viability and increased cell inhibition. The inhibition data were subjected to Probit analysis using SPSS software, which determined the IC50 value to be 44.06 μg/mL. Based on the IC50 value, the activity of nanocurcumin, which was further analyzed at 100, 50, and 25 µg/mL concentrations, is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3

Effect of various concentrations of nanocurcumin on cells viability and inhibition. The data are displayed as the mean ± standard deviation. The variance letters (a, ab, abc, bc, cd, d, e for cell viability in Figure 3A; and a, b, c, d, e, f for cell inhibition in Figure 3B) signify statistical differences at p ≤ 0.05 according to the Mann–Whitney U Test.

3.3. HOX mRNAs relative expressions

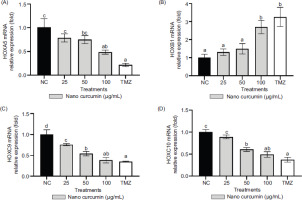

The relative expressions of HOXA5, HOXB1, HOXC9, and HOXC10 mRNAs were assessed using qRT-PCR, with GAPDH serving as the housekeeping gene for normalization purposes. In Figure 4, the alterations in gene expression resulting from nanocurcumin and TMZ treatments were depicted, with statistically significant changes indicated by p-values below 0.05. The figure revealed notable reductions in the relative expressions of HOXA5, HOXC9, and HOXC10 mRNAs, along with an increase in the relative expression of HOXB1 mRNA. These findings highlighted that a 100 μg/mL concentration of nanocurcumin prominently influenced the downregulation of HOXA5, HOXC9, and HOXC10 expressions, as well as the upregulation of HOXB1 expression.

Figure 4

Effect of various nanocurcumin concentrations on mRNA relative expressions of HOXA5, HOXB1, HOXC9, and HOXC10. The experimental groups consisted of: 1) NC: Negative control or untreated cells; 2) U87 cells treated with nanocurcumin at concentrations of 25 μg/mL, 50 μg/mL, and 100 μg/mL; and 3) TMZ: U87 cells treated with TMZ at a concentration of 300 μM. The data are displayed as the mean ± standard deviation. In Figure 4A (HOXA5), the variance of letters (a, ab, bc, and c) indicates statistical differences at p ≤ 0.05 according to the Tukey Post Hoc Test. In Figure 4B (HOXB1), the variance of letters (a and b) signifies statistical differences at p ≤ 0.05 based on the Tukey Post Hoc Test. In Figure 4C (HOXC9), the variance of letters (a, ab, b, c, and d) represents statistical differences at p ≤ 0.05 determined by Dunnett’s T3 Post Hoc Test. In Figure 4D (HOXC10), different letters (a, ab, b, and c) indicate statistical differences at p ≤ 0.05 as determined by the Tukey Post Hoc Test.

3.4. Apoptotic, Live, and Necrotic Levels in U87 Cells

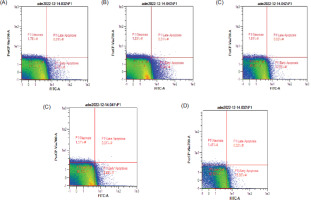

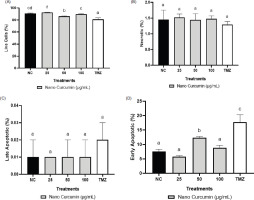

Figure 5 displays representative dot blots illustrating the effects of nanocurcumin at 100, 50, and 25 µg/mL concentrations on cell apoptosis. The data presented in Figure 6 indicate a reduction in the quantity of GBM cells following treatments with TMZ and nanocurcumin, which led to a rise in the count of early apoptotic cells. TMZ at a concentration of 300 μM significantly increased the percentage of late and early apoptotic cells, reaching the highest level. On the other hand, treatment with only a 50 μg/mL nanocurcumin concentration resulted in a significant increase in early apoptosis.

Figure 5

The dot blot images demonstrate the apoptotic levels of U87 cells in response to different concentrations of nanocurcumin, as assessed by flow cytometry. The apoptotic profiles for each treatment group are as follows: (A) Negative control: Live cells: 91.52%, Necrotic: 1.76%, Early Apoptotic: 6.71%, Late Apoptotic: 0.01%; (B) U87 cells treated with nanocurcumin 25 μg/mL: Live cells: 92.72%, Necrotic: 1.53%, Early Apoptotic: 5.74%, Late Apoptotic: 0.01%; (C) U87 cells treated with nanocurcumin 50 μg/mL: Live cells: 85.52%, Necrotic: 1.61%, Early Apoptotic: 12.85%, Late Apoptotic: 0.02%; (D) U87 cells treated with nanocurcumin 100 μg/mL: Live cells: 90.15%, Necrotic: 1.57%, Early Apoptotic: 8.28%, Late Apoptotic: 0.01%; and (E) U87 cells treated with TMZ 300 μM: Live cells: 82.63%, Necrotic: 1.41%, Early Apoptotic: 15.93%, Late Apoptotic: 0.02%.

Figure 6

Effect of various concentrations of nanocurcumin on apoptotic, necrotic, and live cell levels. (A) Live cell levels; (B) Necrotic levels; (C) Late apoptotic levels; (D) Early apoptotic levels. *Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. The groups are NC: negative control/untreated cells; U87 cells treated with nanocurcumin at 25 μg/mL, 50 μg/mL, and 100 μg/mL; and TMZ: U87 cells treated with TMZ 300 μM. Different letters (a, b, c, cd, d) in Figure 6A (live cells) indicate statistical differences at p ≤ 0.05 based on the Dunnett T3 Post Hoc Test. Letter (a) in Figure 6B (necrotic cells) indicates that there is no statistically significant difference based on the Tukey Post Hoc Test. Letter (a) in Figure 6C (late apoptotic cells) indicates no statistically significant difference based on the Tukey Post Hoc Test. Differences in letters (a, b, c) in Figure 6D (early apoptotic cells) indicate statistically significant differences at p ≤ 0.05 based on the Dunnett T3 Post Hoc Test.

4. DISCUSSION

The measurement of zeta potentials for nanoparticles is generally straightforward and is often recommended as a necessary characteristic to include for comprehensive nanoparticle characterization (Lowry et al., 2016). The zeta potential, which is influenced by surface charge, is essential for the nanoparticles’ initial attachment to the cell membrane and for maintaining their stability in suspension. Additionally, the rate of endocytotic uptake following adsorption is affected by the size of the particles. Consequently, both the zeta potential and particle size impact the nanoparticles’ toxicity (Rasmussen et al., 2020).

The Particle Size Analyzer (PSA) is a device designed to measure particle sizes by leveraging the principle of dynamic light scattering method was applied to measure the particle size distribution undergoing Brownian motion. Curcumin extract nanoparticles exhibited a 275.88 nm average particle size with five repetitions (Table 2). This indicates that the curcumin extract-derived nanoparticles meet the criteria for classification as nanoparticles, which are defined as having a size range between 1 and 1000 nm (Syarmalina et al., 2019).

Glioblastoma (GBM) is known as a prevalent and highly aggressive primary malignant brain tumor globally. It is characterized by enhanced angiogenesis, rapid cell proliferation, invasion into healthy brain tissue, and the presence of necrotic areas (Ostrom et al., 2018). The current strategies for managing GBM typically entail a multidisciplinary approach consisting of surgical intervention, radiation therapy, chemotherapy employing TMZ, and supportive care, which aim to extend patients’ life expectancy (Hanif et al., 2017). However, the use of TMZ as a standard chemotherapy adjuvant has certain limitations, including its high cost and numerous side effects (Sengupta et al., 2012). Epidemiological research has provided evidence of the potential of natural food compounds to hinder the growth and spread of tumors. Curcumin is known as a compound from turmeric, which is a natural compound (Ravindran et al., 2009; Paulraj et al., 2019). However, curcumin efficacy is compromised due to its limited solubility, limited bioavailability, and rapid metabolism by enzymes (Zheng and McClements, 2020). The formulation of nanocurcumin offers a prospective method for achieving better drug delivery and improve GBM treatment efficacy. By efficiently and precisely interacting with tumor target cells, nanocurcumin addresses the challenges associated with curcumin’s poor bioavailability and limited solubility, thereby increasing its therapeutic effectiveness in GBM.

In this study, the implication of nanocurcumin on the cell viability assay and inhibition was investigated in U87 cells at various concentrations (Figure 3). The results demonstrated that nanocurcumin effectively reduced cell viability by increasing cell inhibition in a concentration-dependent manner. Higher concentrations of nanocurcumin led to lower cell viability and higher levels of cell inhibition. Analysis of the inhibition data using Probit SPSS revealed an IC50 value of 44.06 µg/mL for nanocurcumin. A separate study reported that curcumin showed significant effects in inducing apoptosis and reducing proliferation in MCF-7 breast cancer cells, especially at concentrations exceeding 10 µM. It has been observed that a compound can reduce cell viability by exerting anti-proliferative effects or inducing apoptosis by suppressing the activity of protein tyrosine kinase, Bcl-2 mRNA expression, c-myc mRNA expression, protein kinase C activity, and thymidine kinase activity (Zhou et al., 2016).

In Figure 4A, the data demonstrate that treatment with a 100 µg/mL nanocurcumin concentration resulted in a reduction of HOXA5 gene expression. The reduction of HOXA5 expression is important because multiple researches have documented that high levels of HOXA5 expression promote tumor development, including in esophageal and breast cancer (Zhang et al., 2017; Teo et al., 2016). This study revealed a correlation between increased HOXA5 expression and malignant clinical features, such as high-grade glioma and enhanced cell proliferation capabilities. HOXA5 can influence the responsiveness of glioblastoma cells to radiation therapy (Cimino et al., 2018). The use of nanocurcumin exhibited a significant effect in suppressing GBM growth. Figure 4B shows increased HOXB1 gene expression in the GBM cells treated with nanocurcumin. Interestingly, downregulation of HOXB1 gene expression enhances the invasion and proliferation of glioma cells while inhibiting apoptosis in vitro. Moreover, immunohistochemical and bioinformatic analyses indicate that HOXB1 downregulation is in accordance with poorer longevity in glioma patients (Han et al., 2015). These findings support the current research results, highlighting the ability of nanocurcumin at a 100 µg/mL concentration to enhance the expression of the HOXB1 gene, potentially offering cellular protection.

Figure 4C illustrates that nanocurcumin therapy in GBM cells leads to a reduction in HOXC9 gene expression. These findings are in line with the research conducted by Xuan et al., (2016) who utilized microarray-based analysis on two databases (Glioma-French-284 Tumor and Glioma-French-95 Tumor) and observed a strong association between high HOXC9 expression and poor outcomes (Xuan et al., 2016). Conversely, low expression of HOXC9 correlated with favorable survival. Therefore, a decrease in HOXC9 gene expression at a 100 μg/mL concentration is a promising indication. Figure 4D discovered a positive correlation between HOXC10 expression and immunosuppression genes (CCL2, TGF-â2, PD-L2, TDO2) (Li et al., 2018). Further investigation showed that HOXC10 potentially binds to TDO2 and PD-L2, thereby promoting transcription and facilitating immune evasion, which are characteristic features of tumors (Tan et al., 2018). Consequently, if HOXC10 gene expression is not suppressed or reduced, it can contribute to glioblastoma malignancy by increasing immunosuppression genes that facilitate tumor progression. These findings emphasize the capacity of nanocurcumin at a 100 μg/mL concentration for further candidate consideration.

This research also investigated the consequences of nanocurcumin at the 25, 50, and 100 μg/mL concentrations on live, necrotic, and apoptotic cells in U87 cells using flow cytometry (Figure 5). The findings demonstrated that nanocurcumin at a 50 μg/mL concentration had the most effectiveness in reducing live cells in comparison with the negative control and showed similar efficacy to TMZ treatment (Figure 6A). These findings are in line with previous research showing that curcumin compounds can suppress the growth of Glioblastoma Stem-like Cells (GSC) by inhibiting cell proliferation and survival, regulating antitumor signaling pathways, disrupting molecular signals, activating apoptosis, and inhibiting cell cycle progression (Zhuang et al., 2012). Moreover, another study highlighted the superior effectiveness of nanocurcumin in comparison with free curcumin dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) in reducing the viability of other tumor cells, including A431 (epidermoid carcinoma), HepG2 (liver carcinoma), and A549 (lung carcinoma) (Basniwal et al., 2014). Necrosis refers to uncontrolled cell death that can result from injury or infection and involves changes in the cell nucleus leading to its lysis and rupture of the plasma membrane (Zhang et al., 2018). The development of necrosis can worsen tumors, necessitating preventive measures such as inhibiting necrosis factors, including pro-inflammatory proteins like TNF-á. The findings of this study prove that nanocurcumin exhibited a favorable effect in reducing necrosis, although there were no notable distinctions observed among the tested concentrations (Figure 6B). Another study showed that curcumin-encapsulated liposome nanoparticles were more efficient in inducing cell cycle arrest, inducing cell apoptosis, and causing necrosis in GSCs compared with free curcumin (Sahab-Negah et al., 2020), and consistent with these findings, the cytotoxicity of nanocurcumin on tumor cells has been associated with membrane damage, which can occur through apoptosis (Hanna and Saad, 2020).

Apoptosis is a tightly regulated physiological mechanism of cellular demise. It functions to eliminate cells that are no longer required, extensively injured, mutated, or aged and cannot be repaired, thereby preserving the overall integrity of both the individual cell and the organism (Singh et al., 2019). Apoptosis serves as a vital mechanism in preventing the excessive proliferation and metastasis of tumors to other organs. In this study, nanocurcumin at the 50 μg/mL concentration demonstrated a more constructive induction of both early and late apoptosis (Figure 5C–D) compared to the negative control, closely resembling the results obtained with TMZ treatment. Curcumin compounds are known to target various apoptotic mechanisms, spanning a broad range of molecular regulators; transcriptional modulators such as AP-1 and NF-êB; growth-signaling factors including EGF and VEGF; inflammatory enzymes like COX-2; key kinase pathways such as AMPK and PKC; and pro-inflammatory mediators including IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-á; membrane receptors; and molecular signaling pathways (Shehzad et al., 2013; Ismail et al., 2019). The nanocurcumin apoptotic effect observed in this study closely resembles that of TMZ treatment, which is a synthetic chemical drug exerting a cytotoxic effect on glioblastoma cells through an apoptotic mechanism (Scott et al., 2011).

Investigations have indicated that curcumin exhibits the capacity to attenuate the malignant properties of GBM stem cells and enhances the effectiveness of radiation therapies and modern chemotherapy by selectively triggering apoptosis in cancer cells while protecting healthy tissues (Fratantonio et al., 2019). Engineered nanocurcumin, with a size ranging from approximately 1–100 nm, holds promise as a therapeutic agent with an effective, controlled, and targeted drug delivery system (Rudramurthy et al., 2016). Nano-sized curcumin capsules have been extensively employed for the treatment of GBM cells. A previous study illustrated that nanocurcumin can impede the growth of GBM by inhibiting cell proliferation and reducing the population of stem-like tumor cells (Yin et al., 2014). Another study demonstrated the successful utilization of curcumin-containing Fe3O4-magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) that exhibited perfect absorption and facilitated drug release within tumor tissue, and this formulation also demonstrated imaging capabilities in tumor tissue (Aeineh et al., 2018). More recently, PEGylated curcumin-decorated magnetic nanoparticles were identified as highly compatible drug carriers for antitumor medications (Ayubi et al., 2019). Hence, nanocurcumin shows potential in treating GBM by downregulating the expression of HOXA5, HOXC9, and HOXC10 genes, while upregulating the expression of the HOXB1 gene. Likewise, nanocurcumin was more effective in suppressing tumor growth than curcumin; furthermore, nanocurcumin contributes to the reduction of live cells and necrosis, as well as the encouragement of early and late apoptosis in GBM U87 cells.

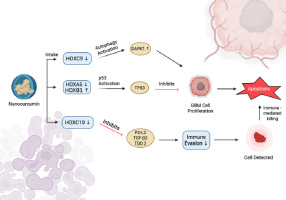

A molecular schematic of nanocurcumin’s mechanistic activity illustrates a coordinated modulation of multiple HOX genes, inducing both tumor-intrinsic and immune-mediated apoptotic pathways in GBM cells. One of the significant changes is the downregulation of HOXC9, which leads to the upregulation of DAPK1. DAPK1 is a serine/threonine kinase involved in autophagy induction, and autophagy has been reported as a significant tumor-suppressive mechanism, especially in gliomas, by mediating cell death or apoptosis in response to metabolic or oxidative stress (Singh et al., 2016). Thus, by promoting increased DAPK1 activity, nanocurcumin can be considered a pro-autophagic compound that helps to mediate cellular degradation and apoptosis in GBM.

At the same time, nanocurcumin downregulates HOXA5 and upregulates HOXB1, culminating in the activation of the tumor suppressor gene TP53. The p53 signalling is a pathway that mediates anticancer responses, for example, cell cycle arrest, DNA repair, and intrinsic apoptosis (Carlsen et al., 2023; Vazquez et al., 2008; Pitolli et al., 2019). The reactive pathway observed in this study plays a crucial role in GBM, where mutation of p53 is frequently found and contributes to uncontrolled cell proliferation and resistance to apoptosis. Thus, exposure to nanocurcumin could work to reverse proliferative capacity and restore the apoptotic function in tumor cells that previously was lost. This explains the GBM cell proliferation suppression and the subsequent induction of apoptotic cell death as demonstrated in this study.

Moreover, this study showed that nanocurcumin exerts immunomodulatory effects through the downregulation of HOXC10. This activity decreases the expression of PD-L2, TGF-â2, and TDO2, which are key immunosuppressive mediators involved in tumor immune escape through T-cell anergy, regulatory T-cell proliferation, and immune suppression via tryptophan metabolism (Badawy, 2022). Inhibition of these immunosuppressive mediators is essential for restoring effective anti-tumor immune surveillance. Following systemic blockade of these pathways, the reduction in immunosuppression enhances the ability of cytotoxic lymphocytes to recognize and destroy tumor cells. This process is reflected by an increase in immune-mediated apoptosis, as illustrated in Figure 7.

Figure 7

Schematic illustration of molecular mechanisms of apoptosis induction by nanocurcumin in Glioblastoma (GBM) cells via HOX gene modulation. Downregulation of HOXC9 activates autophagy through DAPK1, while altered expression of HOXA5 and HOXB1 induces p53 (TP53) activation and inhibits the proliferation of GBM cells. Decreased expression of HOXC10 inhibits the expression of immunosuppressive mediators (PD-L2, TGF-â2, TDO2), which reduces immune evasion and increases immune-mediated apoptosis.

The results support nanocurcumin as a multi-target therapeutic agent that rewires oncogenic and immunosuppressive pathways via HOX gene modulation, providing a mechanistic basis for its use as a multi-drug adjuvant or synergistic agent to induce autophagy, reactivate p53, and re-sensitize tumor immune cells.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Nanocurcumin therapy demonstrates promising effects in reducing cell viability in GBM U87 cells. It effectively decreases the expression of HOXA5, HOXC9, and HOXC10 genes, while increasing HOXB1 gene expression. Nanocurcumin treatment is also associated with a decline in viable cells and necrosis, along with an elevation in both early and late apoptosis in U87 GBM cells. These findings highlight the prospective potential of nanocurcumin as an alternative therapeutic approach for the treatment of GBM tumors.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are deeply grateful to Aretha Medika Utama, Biomolecular and Biomedical Research Center, Bandung, Indonesia, for their support in providing the materials needed for this research.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

R.A. conceived and designed the study, coordinated the research workflow, performed data analysis, and led the manuscript writing. W.W., D.D., and D.R. carried out data collection, laboratory procedures, and assisted in manuscript drafting. A.F., D.N.T., and A.M.N. contributed to data curation, interpretation, and literature review. R.A. and W.W. provided technical validation, supervised analytical methods, and revised the manuscript critically. D.L.S. and D.S.H. participated in visualization and data presentation. K.S.A. reviewed the final formatting of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.