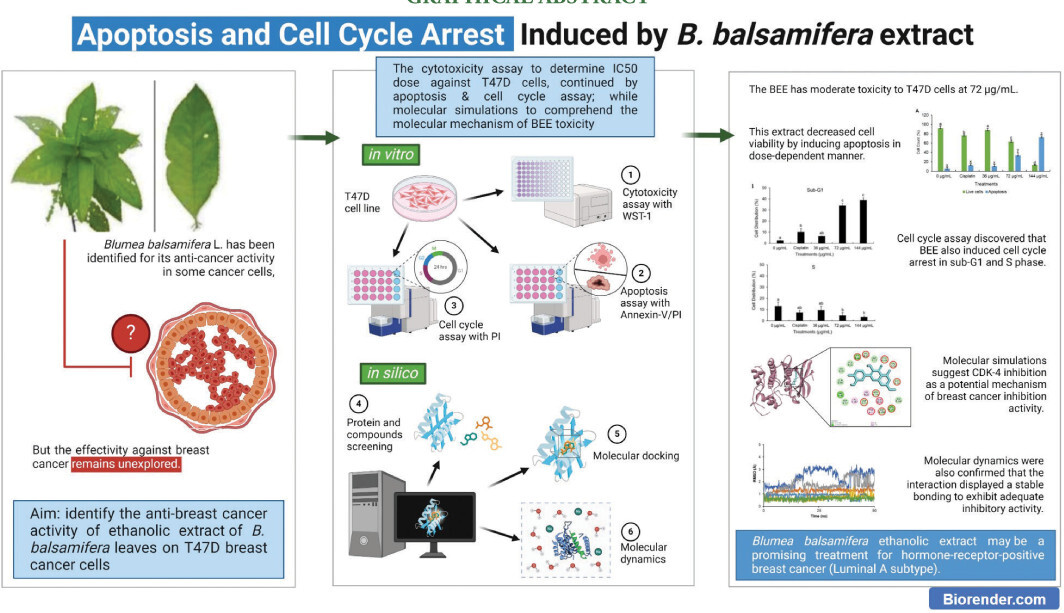

1. Introduction

As of the year 2020, breast cancer has surpassed lung cancer in terms of being the most often diagnosed form of malignancy on a global scale. It holds the fifth position in terms of cancer-related deaths, with an estimated 2.3 million reported cases and 685,000 associated fatalities (Lei et al., 2021). The prognosis of human breast cancer depends on several aspects, such as the ability to respond to estrogen and the dependence on hormones (Shokrollahi et al., 2015). The prevailing molecular subtype within breast cancer classifications is luminal A breast cancers, which are distinguished by their ER+PR+HER2- profile. The T47D cell line is widely recognized as a suitable model for studying luminal A breast cancer because of its noninvasive nature and low-grade characteristics, which are derived from the breast duct (Brown et al., 2019). The utilization of these cell lines holds great significance as experimental tools. They enable investigations into the origins of breast cancer, clarify the mechanisms of cell proliferation and differentiation, and support the development of novel strategies for inducing apoptosis. Consequently, these cell lines contribute to the enhancement of treatment modalities (Shokrollahi et al., 2015).

The treatment protocols for breast cancer commonly involve a diverse range of interventions, including surgical procedures, chemotherapy, radiation, and hormone therapy (Cheung, 2020). Unfortunately, these treatment methods frequently cause negative side effects, such as hair loss (alopecia), nausea, changes in skin and nail color, headache, gastrointestinal issues like diarrhea and stomach cramps, dry mouth (xerostomia), and cognitive impairment (Aslam et al., 2014; Effendi and Anggun, 2019). Given the challenges posed by these side effects, there is growing interest in exploring the advantages of plant-derived natural products as adjunctive therapies. These natural products offer the potential for efficacy along with a lower toxicity profile compared to synthetic drugs (Ko and Moon, 2015).

The presence of diverse active compounds in plants renders them a promising source for targeting cancer cells through multiple mechanisms (Mitra and Dash, 2018). Furthermore, the integration of bioactive compounds derived from plants into traditional treatment regimens holds promising potential. This approach may help mitigate the adverse effects of therapy, reduce the risk of cancer-related complications, and modulate immune responses, thereby enhancing the overall well-being of patients (Lee et al., 2022; Yin et al., 2013). These benefits elucidate the growing interest among patients in utilizing plant-derived natural products as complementary or alternative medications (Rezaeiamiri et al., 2020).

Blumea balsamifera L. has a rich historical background in traditional herbal medicine throughout Southeast Asian countries (Pang et al., 2014). It has attracted considerable interest because of its possible therapeutic attributes in the field of cancer treatment. The effectiveness of B. balsamifera extract in inhibiting the growth of liver cancer cells, while causing minimal harm to healthy liver cells, has been demonstrated in previous studies (Ng et al., 2010; Widhiantara and Jawi, 2021). In addition, the extract of B. balsamifera has been shown to include dihydroflavonols that have synergistic effects when combined with TRAIL, a ligand associated with cell death, leading to the induction of apoptosis in adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATLL) (Hasegawa et al., 2006). Furthermore, previous research has successfully identified distinct chemical constituents present in B. balsamifera extract, including Luteolin-7-methyl ether, Quercetin, dihydroquercetin-7,4’-dimethyl ether, 5,7,3’5’Tetrahydroxyflavanone, and Blumeatin. These compounds have been found to possess inhibitory properties against cell lines associated with small cell lung and oral cancer (Saewan et al., 2011).

Although the anti-breast cancer properties of B. balsamifera have been fully understood, its effectiveness against luminal A type breast cancer is still not well understood. Consequently, the primary objective of this research was to investigate the potential anti-cancer properties of B. balsamifera ethanolic extract (BEE) on the T47D breast cancer cell line, which serves as a representative of the luminal A type. This investigation was conducted in vitro and supplemented with in silico analysis to gain a comprehensive understanding of the molecular mechanism underlying the anti-breast cancer activity of BEE.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant material extraction

B. balsamifera leaves were purchased from Materia Medica, Batu, East Java, Indonesia, in the form of dried powder. Extraction was conducted in accordance with a prior investigation conducted by (Widyananda et al., 2022b). The experimental procedure included microwave-assisted extraction (MAE), utilizing a mixture of 6 g of dried powder plant material and 60 mL of 96% ethanol in a 1:10 ratio for each vessel. The MAE process consisted of subjecting the sample to a temperature of 50°C for a duration of 10 minutes, followed by a subsequent cooling period of 5 minutes. The extract obtained was collected and subjected to filtration using filter paper, after which the solvent was evaporated using a vacuum rotary evaporator to obtain BEE. The BEE crude extract was thereafter collected and kept at a temperature of 4°C.

2.2. Cell viability assay

The cell viability assay was conducted in accordance with a previous study (Fitriana et al., 2022). T47D cells, which are used as a representative model for luminal A type of breast cancer, were cultured in complete RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin for 48–72 hours in 5% CO2 environment at a temperature of 37°C. Once confluency was achieved, the cells were subsequently placed into a 96-well plate at a concentration of 7.5 x 103 cells per well and placed in the incubator for 24 hours. After this period of incubation, the medium was substituted with different concentrations (0, 50, 100, 200, and 400 µg/mL) of BEE, followed by additional 24-hour incubation period under identical conditions. After the completion of the treatment, the medium was substituted with a new medium that contained 5% WST-1 reagent and subjected to incubation for a duration of 30 minutes. The microplate reader was used to detect cell absorbance at a wavelength of 450 nm. The absorbance then converted into percentage of viable cell referring to the previous detailed equations. The obtained percentage of viable cells per treatment group were then used to calculate the inhibition concentration 50 (IC50) for subsequent experiments.

2.3. Apoptosis assay

Cells were seeded in 24-well plates at a density of 7.5 x 104 cells/well and incubated under conditions of 5% CO2 at 37°C for 24 hours. Subsequently, the cells were treated with different concentrations (0, 0.5 × IC50, IC50, and 2 × IC50) of BEE. Cisplatin was used as the control drug at a dose 4 µg/mL. The treated cells were then incubated for 24 hours under the same conditions. After the treatment period, the medium was removed, and the cells were harvested and washed with 400 µL of PBS. The cells were then centrifuged at 2,500 rpm at 10°C for 5 minutes, followed by resuspension in 50 µL of Annexin V – propidium iodide (PI) solution, and incubated in the dark at 4°C for 30 minutes. Afterward, 400 µL of PBS was added to the cells, and the cell suspension was analyzed using flow cytometry with BD Cell Quest software (Fitriana et al., 2022).

2.4. Cell cycle assay

Cells were seeded in 24-well plates at a density of 7.5 x 104 cells/well and incubated under conditions of 5% CO2 at 37°C for 24 hours. Subsequently, the cells were treated with different concentrations (0, 0.5 × IC50, IC50, and 2 × IC50) of BEE and 4 µg/mL of cisplatin, then incubated for 24 hours under the same conditions. After the treatment period, the medium was removed, and the cells were harvested and washed with 400 µL of PBS. The cells were then centrifuged at 2,500 rpm at 10°C for 5 minutes, and the supernatant was discarded. The cells were resuspended in 70% ethanol and incubated in the dark at 4°C for 30 minutes. Afterward, the supernatant was discarded, and 1 mL of PBS was added to the cells. The cells were centrifuged again at 2,500 rpm at 10°C for 5 minutes, and the supernatant was discarded. Subsequently, 50 µL of PI and RNAse were added to the cells, and the mixture was incubated in the dark at 37°C for 30 minutes. Finally, 400 µL of PBS was added to the cells, and the cell suspension was analyzed using flow cytometry with BD Cell Quest software (Widyananda et al., 2022a).

2.5. Data analysis

The percentage of viable cells and relative number of cells from apoptosis and cycle cell assay were analyzed using one-way ANOVA. If the p value < 0.05, post-hoc analysis was performed by Tukey HSD. The group was determined as significantly different if p < 0.05.

2.6. Structure retrieval for molecular simulation

The list of 16 compounds of B. balsamifera was obtained from the KnapSack database (http://www.knapsackfamily.com/knapsack_core/top.php). The PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) was utilized to obtain further compound data, which encompassed PubChem ID, canonical SMILES, and three-dimensional structures. The structures of protein cyclin-dependent kinase-2 (CDK-2), CDK-4, and CDK-6 were retrieved from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) database with PDB ID 4KD1, 2W9Z, and 5L2I, respectively (Chen et al., 2016; Day et al., 2009; Martin et al., 2013). The native ligand structures from CDK-2 and CDK-6 (Dinaciclib and Ribociclib) were extracted from the crystallized structure, while Abemaciclib (PubChem CID 46220502) was downloaded from PubChem (El Hachem et al., 2021).

2.7. Ligand and receptor preparation

Dinaciclib and Ribociclib were selected as the control ligand for CDK-2 and CDK-6, respectively. On the other hand, Abemaciclib was chosen as the control molecule for CDK-4. Energy minimization was performed on the compounds, including Abemaciclib, using the Open Babel (O’Boyle et al., 2011) software incorporated into PyRx 0.8 (Dallakyan and Olson, 2015). The ligands employed in the molecular docking procedure were derived from the energy-minimized structures obtained. In Discovery Studio 2019, the protein structure of CDK-4 was meticulously produced by eliminating solvents, undesired ligands, and unrelated chains (Syahraini et al., 2023). The protein structure that had been optimized was subsequently imported into the PyRx software in the form of a macromolecule, which would be utilized in the molecular docking procedure.

2.8. Molecular docking, interaction analysis, and structural visualization

AutoDock Vina 1.2.5 (Eberhardt et al., 2021) was utilized for molecular docking within the PyRx interface. The binding affinity and structural conformations were calculated using a specific docking technique in the molecular docking analysis. In accordance with prior methodologies (Hermanto et al., 2019), the ligands were considered as flexible entities, whilst the macromolecule retained its rigidity. Table 1 provides a complete overview of the grid configurations utilized in the specific docking method. The analysis of the interactions between CDK-4 residues and each ligand was conducted using Biovia Discovery Studio; the same software also facilitated structural visualization.

Table 1

Protein target identity and grid coordinates for specific docking

| Protein | PDB ID | Active site | Ref. | Grid coordinate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Center | Dimension | ||||

| CDK-2 | 4KD1 | Ile10, Gly11, Val18, Ala31, Lys33, Val64, Phe80, Glu81, Phe82, Lys89, Leu134, Ala144, Asp145 | (Martin et al., 2013) | X: 54.954 | X: 23.696 |

| Y: 77.223 | Y: 18.504 | ||||

| Z: 26.318 | Z: 18.551 | ||||

| CDK-4 | 2W9Z | Ile12, Val14, Gly15, Ala16, Tyr17, Lys35, Phe93, Asp99, Lys142, Glu144, Asn145, Asp, 158 | (Nagare et al., 2023) | X: 21.257 | X: 18.703 |

| Y: 21.624 | Y: 17.074 | ||||

| Z: 11.052 | Z: 16.386 | ||||

| CDK-6 | 5L2I | Ile19, Val27, Ala41, Val77, Phe98, Glu99, Val101, Gln103, Asp104, Gln149, Asn150, Leu152, Ala162, Asp163 | (Chen et al., 2016) | X: 17.057 | X: 18.039 |

| Y: 28.321 | Y: 20.964 | ||||

| Z: 8.376 | Z: 19.790 | ||||

2.9. Molecular dynamics

The YASARA software (Krieger and Vriend, 2015) was utilized to perform molecular dynamics simulations, adhering to the simulation protocol outlined in prior research (Hermanto et al., 2022). To mimic cellular physiological conditions, the system settings were modified to maintain a temperature of 310°K, pH 7.4, atmospheric pressure (1 atm), a NaCl concentration of 0.9%, and a water density of 0.997 g/mL. The AMBER14 force field (Maier et al., 2015) was utilized to conduct the simulations, with a period of 50 nanoseconds. The criteria used to evaluate structural stability were the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of atomic positions and the root-mean-square fluctuations (RMSF) of residue movements (Rohman et al., 2023). Furthermore, the quantity of hydrogen bonds established between the protein and ligand was regarded as a measure of the stability of the protein–ligand interaction (Susilo et al., 2024).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. BEE Induces Toxicity to T47D Cell Lines

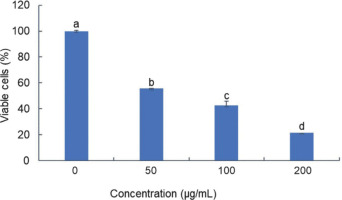

The toxicity assessment of BEE on T47D cells revealed a dose-dependent reduction in cell viability as extract concentrations increased. When the concentration of BEE was at its lowest, it caused cell death in more than 40% of the entire cell population. It is worth mentioning that the third dose (200 µg/mL) exhibited the most pronounced toxicity, as evidenced by a survival rate of only 20% among the entire cell population following the treatment. The IC50 value was determined to be 72 µg/mL based on the toxicity findings. This value signifies that the extract, when present at a concentration of 72 µg/mL (further determined as the IC50 of BEE), can impede the viability of T47D cells by 50% of the entire cell population (Figure 1). The extract’s anti-cancer activity was classified into four categories according to IC50 values (Nordin et al., 2018), with BEE being classified as having moderate toxicity.

Figure 1

Toxicity profile of BEE against T47D cell. The bar-chart was visualized according to the mean and standard deviation value. Different alphabetical notations indicate the statistical significance according to Tukey post-hoc analysis at 95% confidence level.

The IC50 serves as a critical parameter, offering valuable insight into the potential of BEE as a therapeutic agent for breast cancer. The present findings exhibit a notable divergence from a prior investigation that characterized the methanolic extract of B. balsamifera as exhibiting a comparatively lower level of toxicity toward the T47D cell line (Ng et al., 2010). According to a previous study (El Mannoubi, 2023), ethanol has been demonstrated to dissolve a larger amount of bioactive chemicals than methanol. Thus, ethanolic extract of B. balsamifera is stronger than methanolic extract in exhibiting anti-cancer properties. This highlighted the importance of considering extraction methods and their impact on the efficacy of herbal extracts in eliminating cancer.

The toxic properties of B. balsamifera on cancer cells are believed to be attributed to its rich phytochemical constituents. Previous studies have identified that the ethanol extract of B. balsamifera contains quercetin, a flavonoid compound that has demonstrated significant anti-breast cancer activity in various experimental models (Kamila et al., 2025; Ryu et al., 2019). Moreover, other investigations have reported the presence of several bioactive compounds in B. balsamifera with promising anti-cancer potential, further supporting its therapeutic relevance in oncology (Pang et al., 2014).

3.2. BEE toxicity against T47D was achieved through apoptotic mechanism

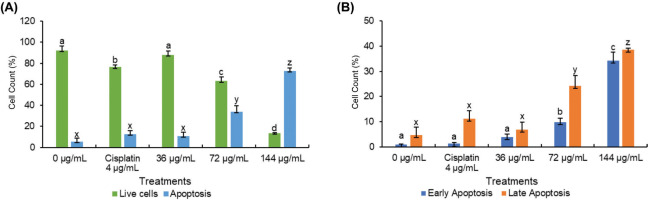

To elucidate the mechanism underlying BEE toxicity against the T47D cell line, flow cytometry analysis was conducted using the Annexin V/PI staining method to identify apoptotic cells. Three doses were employed, corresponding to 0.5, 1, and 2 times the IC50 value (36 µg/mL, 72 µg/mL, and 144 µg/mL) as determined from previous experiments. Consistent with the toxicity findings, BEE induced apoptosis in T47D cells in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 2A). The flow cytometry analysis revealed a predominance of cells in late-stage apoptosis compared to early apoptosis (Figure 2B). Notably, BEE exhibited a significantly greater capacity to induce apoptosis in T47D cells compared to cisplatin, particularly at the IC50 concentration and at twice the IC50 (Figure 2). Collectively, these data suggest that BEE possesses a robust pro-apoptotic activity.

Figure 2

The flow cytometry analysis determines the total number of viable, apoptotic, and necrotic cells. The data were represented in a quadrant plot of flow cytometry gating analysis (A) and a bar chart based on the gating results (B). The mean ± standard deviation was used to present the value. The statistical significance of Tukey analysis at a 95% confidence level is denoted by different alphabetical notation for each parameter.

Preferentially directing cellular death through the apoptosis pathway is more advantageous in cancer treatment, especially when compared to necrosis. Apoptosis is the favored method of cell death compared to necrosis because it is more efficient at causing cell demise without causing inflammation or damage to nearby healthy tissues (Johnstone et al., 2002). In spite of being identified as an agent capable of inducing cell cycle arrest, the apoptotic potential of B. balsamifera remains largely unexplored. While its apoptotic effects have been documented solely in ATLL (Hasegawa et al., 2006), its impact on other cancer cell types remains unreported. Hence, this study represents the inaugural investigation into the apoptotic activity of B. balsamifera, specifically focusing on its effects on T47D breast cancer cells.

Caspase-3 activation is a definitive marker of apoptosis and complements Annexin V data in confirming programmed cell death. In breast cancer, particularly the luminal A subtype, CDK4 inhibition has been shown to trigger apoptosis by activating caspase-3. Recent findings indicate that treatment with CDK4/6 inhibitors such as abemaciclib leads to increased cleaved caspase-3 levels, reinforcing their role in apoptosis induction and therapeutic potential in hormone receptor-positive breast cancer (He et al., 2025).

3.3. BEE exhibits cell cycle arrest at sub-G1 phase

Both cisplatin and BEE had significant effects on the progression of the cell cycle in T47D cells, especially notable in the sub-G1 phase (Figure 1A). Significantly, BEE has shown a greater ability to cause cell cycle arrest in the sub-G1 phase compared to cisplatin (p<0.05). The effect of arresting the cell cycle was particularly significant at concentrations of 72 and 144 µg/mL. In addition, BEE inhibited the growth of T47D cells at the same dosages, demonstrated by a decrease in the number of cells in the S phase, when compared to the control and cisplatin treatments. Cisplatin and BEE had significant effects on the progression of the cell cycle in T47D cells, especially notable in the sub-G1 phase. The herbal extract demonstrated a markedly stronger capacity to induce cell cycle arrest in the sub-G1 stage relative to the chemotherapeutic agent, as evidenced by the statistically significant difference observed. The effect of halting the cell cycle progression was particularly pronounced at concentrations of 72 and 144 micrograms per milliliter. At these dosages, BEE potently inhibited the growth of T47D cells, as reflected by the marked decrease in the percentage of cells in the S phase when compared to untreated control cells and those exposed to cisplatin alone (Figure 3B).

Figure 3

The profile of cell cycle in T47D after BEE treatments according to flow cytometry analysis. (A) Flow cytometry histogram and (B) bar chart and statistical analysis from flow cytometry histogram. The value is presented as mean ± standard deviation. The differences in letter labels indicate a significant different at 95% confidence interval.

Targeting the advancement of the cell cycle has been identified as a recognized approach in cancer treatment, with the goal of inhibiting cell division. Significantly, BEE has shown a greater ability to cause cell cycle arrest in the sub-G1 phase compared to cisplatin (p<0.05). The effect of arresting the cell cycle was particularly significant at concentrations of 72 and 144 µg/mL. In addition, BEE inhibited the growth of T47D cells at the same dosages. This was demonstrated by a decrease in the number of cells in the S phase, when compared to the control and cisplatin treatments. The presence of cells in the sub-G1 phase of the cell cycle following PI staining suggests that these cells may be experiencing apoptosis or necrosis (Velma et al., 2016). Together with apoptosis data, these discoveries indicate that BEE-induced cell cycle arrest may exceed that caused by cisplatin, suggesting its potential as a more effective chemotherapeutic treatment.

In a previous study, cisplatin’s anticancer effects were shown to operate via apoptosis and induction of cell cycle arrest, notably at sub-G1 and S phases in a time-dependent manner (Velma et al., 2016). Interestingly, the current findings reveal that compared to cisplatin, BEE leads to a higher proportion of cells in the sub-G1 phase and a lower number of cells in the S phase, suggesting a potentially superior anticancer effect of BEE over Cisplatin. Furthermore, the cell cycle arrest-inducing capability of B. balsamifera has been documented in hepatocellular carcinoma, where it specifically targets the G1 phase by downregulating cyclin-E expression and retinoblastoma (Rb) protein phosphorylation, while simultaneously reducing levels of a proliferation-inducing ligand implicated in tumor cell growth stimulation (Widhiantara and Jawi, 2021). Notably, no prior studies have reported on the cell cycle arrest activity of B. balsamifera. Therefore, it is inferred that the anticancer potential of BEE is mediated through the induction of cell cycle arrest in T47D cells.

Cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) are pivotal regulators of cell cycle progression, particularly governing the transition from G1 phase to S-phase (Ding et al., 2020). Alterations in the activity of CDK-2, CDK-4, and CDK-6 can halt cell cycle progression at Sub-G1 and G1 phases (Crozier et al., 2022; Peng et al., 2023). By virtue of their critical functions in cell cycle regulation, CDK inhibitors have emerged as a promising class of therapeutic agents with anti-proliferative activity against various malignancies, notably breast cancer (Mughal et al., 2023). Therefore, molecular simulations were performed in this study targeting CDKs to identify a potential molecular mechanism under B. balsamifera’s phytocompounds in modulating apoptosis and cell cycle arrest.

CDK4 is a key regulator of cell cycle progression, particularly in promoting the transition from the G1 to the S phase (Ding et al., 2020). Inhibition of CDK4 activity disrupts the G1 to S phase checkpoint, leading to cell cycle arrest in the G1 phase and inhibition of DNA replication. This condition activates the p53 pathway, which subsequently triggers apoptotic signaling cascades (Adon et al., 2021; Arisan et al., 2014). As apoptosis progresses, cellular DNA becomes fragmented, leading to the appearance of a sub-G1 population during flow cytometry analysis. Therefore, an increase in the sub-G1 fraction following treatment may reflect apoptosis induced by CDK4 inhibition.

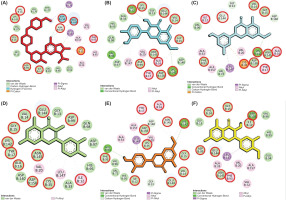

3.4. BEE May inhibit CDK-4 to induce apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in T47D

Molecular docking revealed that most compounds exhibited low binding affinities toward CDK-2, CDK-4, and CDK-6. Notably, several compounds interacting with CDK-4 displayed binding energies surpassing the control inhibitor, Abemaciclib. While most compounds were bound to CDK-2 and CDK-6 with low affinities and did not outperform the control (Table 2), further analysis of interacting residues within the ATP-binding pocket of CDK-4 complexes identified five promising candidates: Blumeatin, Luteolin-7-methyl ether, Quercetin, Rhamnetin, and Taxifolin 4’-methyl ether. Notably, most of these selected compounds, except Quercetin, exhibited a diverse interaction network primarily consisting of hydrogen bonds and π interactions (Figure 4). These interactions are crucial for strong protein–ligand binding. Consequently, these five compounds were chosen for further investigation using molecular dynamics simulations.

Table 2

Binding affinity values of molecular interaction between CDK with control and selected compounds.

Figure 4

Molecular interaction of CDK-4 with control and selected compounds. (A) CDK-4/Abemaciclib (control), (B) CDK-4/Rhamnetin, (C) CDK-4/Blumeatin, (D) CDK-4/Quercetin, (E) CDK-4/Luteolin-7-methyl ether, and (F) CDK-4/Taxifolin 4’-Methyl ether. The residues highlighted with red circles denote their involvement in the active site of CDK-4.

In luminal A breast cancer, characterized by estrogen receptor positivity and low proliferation rates, the cyclin D–CDK4/6 complex is integral to cell cycle progression. This complex facilitates the transition from the G1 to S phase by phosphorylating the Rb protein, thereby promoting cell proliferation. Notably, the activity of cyclin D and CDK4/6 complexes plays a major role in tumor cell proliferation driven by estrogen, especially in breast cancer (Li et al., 2020). While both CDK4 and CDK6 are involved in this process, evidence suggests that CDK4 may have a more prominent role in luminal A subtypes. For instance, studies have demonstrated that CDK4 is essential for ErbB-2-induced mammary tumorigenesis, whereas CDK6 is not, indicating a unique requirement for CDK4 in certain breast cancer contexts (Finn et al., 2016). Furthermore, the clinical efficacy of CDK4/6 inhibitors, such as palbociclib, in hormone receptor-positive breast cancers underscores the therapeutic relevance of targeting CDK4 in luminal A breast cancer (Shanabag et al., 2025).

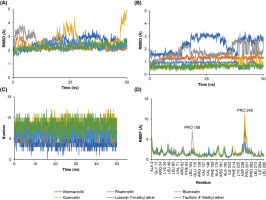

Molecular dynamics simulations were performed to evaluate the stability of the protein–ligand complexes between CDK-4 and the selected ligands. The RMSD analysis of backbone atoms revealed greater flexibility in the CDK-4/Quercetin complex compared to the other complexes (Figure 5A). This observation is further supported by the RMSF analysis of residue movements, which showed a pronounced peak at PRO245 in the CDK-4/Quercetin complex. This increased flexibility likely arises from the lower number of hydrogen bonds and π interactions observed in this complex compared to the others (Figure 4). Interestingly, the overall RMSD profile displayed a similar pattern for all complexes, suggesting that the overall structure of CDK-4 remained relatively unaffected by ligand binding (Figure 5B). This implies that the core structure of CDK-4 maintains stability during the simulations, while the ligand binding pockets exhibit varying degrees of flexibility depending on the specific ligand interaction pattern.

Figure 5

The molecular dynamics simulation of the interaction of CDK-4 with control and selected compounds. (A) RMSD backbone, (B) RMSD ligand, (C) number of hydrogen bond, and (D) RMSF.

The RMSD of ligand conformation was then used to identify the ligand structures’ stability during its binding with the CDK-4. Similar to the RMSF results, the RMSD of ligand conformation described a similar stability information of the ligands. However, slight instability was displayed by Abemaciclib and Blumeatin. Still, the value of the RMSD was below 3 Å, suggesting that those fluctuations may slightly alter the conformational structure of both compounds to perform inhibitory activities (Figure 5C). In addition, the number of hydrogen bonds were also evaluated to understand interaction stability. Hydrogen bonds serve as the most significant interaction during protein–ligand binding (Madushanka et al., 2023). The high number of hydrogen bonds may result in a better inhibitory activity than the one with less number of hydrogen bonds (Susilo et al., 2024). All complexes displayed a similar number of formed hydrogen bonds. However, CDK-4/Abemaciclib showed the smallest number of hydrogen bonds compared to other complexes (Figure 5D).

Molecular dynamics analysis summed up that several compounds from B. balsamifera, that is, Quercetin, Rhamnetin, Luteolin-7-methyl ether, Blumeatin, and Taxifolin 4’-methyl ether, may involve in apoptosis and cell cycle arrest–inducing mechanism of BEE. The inhibitory activity of those compounds occurred by blocking the active sites of the CDK-4. The interaction stability accompanied by the docking results gave a clear possibility that those compounds also have more promising activity as CDK-4 inhibitor than Abemaciclib. However, future studies required to confirm these computational simulations to better comprehend the anticancer activity of BEE, particularly associated with apoptosis and cell cycle regulation.

4. Conclusion

BEE exhibited moderate cytotoxicity (IC50 = 72 µg/mL) on T47D breast cancer cells. Apoptosis and cell cycle assays revealed that BEE induced both apoptosis and cell cycle arrest at the sub-G1 and S phases more effectively than cisplatin. In silico analysis further suggested that several compounds within BEE, including Blumeatin, Luteolin-7-methyl ether, Quercetin, Rhamnetin, and Taxifolin 4’-methyl ether, displayed potential inhibitory activity against CDK-4, potentially modulating cell cycle and apoptosis. The principal novelty of this study lies in the prediction that the ethanol extract of B. balsamifera exhibits anticancer activity against T47D cells, potentially through mechanisms involving apoptosis induction and cell cycle arrest via CDK4 protein inhibition. These findings suggest that BEE could be a promising candidate for developing anticancer agents, particularly for hormone receptor-positive breast cancer (including Luminal A subtype). However, further in vitro and in vivo experiments are necessary to validate the proposed molecular mechanism of action both at the cellular and the individual organism level.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank the AI Center of Universitas Brawijaya for providing access to high-performance computing facilities to perform molecular dynamics simulations.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

FSK did the formal analysis, investigation, writing (original draft preparation); NR performed the formal analysis and project administration; FEH, MHW, & MA were involved in methodology, validation, and writing (review & editing); DRD did conceptualization and supervision; NW was responsible for conceptualization, resources, software, and funding acquisition.