1. INTRODUCTION

Tuberculosis (TB) is a contagious disease caused by a type of bacteria known as Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Health Ministry of RI 2022). According to the World Health Organization’s report in 2022, TB is the leading cause of death worldwide. In 2021, Indonesia was ranked third in terms of TB-related deaths, with a total of 824,000 cases and 93,000 deaths per year, which means that 11 individuals pass away every hour due to this disease (World Health Organization 2023; Hadi et al. 2023; Dabla et al. 2022).

The problem of tuberculosis (TB) has become more complicated due to the emergence of cases of drug-resistant tuberculosis (Dookie et al. 2022; Kanabalan et al. 2021). Treating patients with Multi-drug resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) has become increasingly difficult, as it is TB that is resistant to first-line TB drugs, namely rifampicin and isoniazid. If MDR-TB cases are accompanied by resistance to one or more additional drugs such as pyrazinamide, ethambutol, fluoroquinolones, or the injectable drug capreomycin, it is called Extensively Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis (XDR-TB) (World Health Organization 2023; Purkan et al. 2024; Purkan et al. 2012; Purkan et al. 2016). MDR-TB cases are increasing by 3.5% annually, while XDR-TB cases are growing by 8.5% per year from MDR cases. Indonesia ranked fifth in MDR-TB cases, with a total of 24,000 cases in 2019 (World Health Organization 2023; Purkan et al. 2024).

Pyrazinamide (PZA) is a drug that is recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) for treating tuberculosis (World Health Organization 2023; Karmakar et al. 2020). It is a cost-effective drug that is highly effective in killing M. tuberculosis bacteria, especially semidormant ones, under acidic conditions. Unlike other anti-TB drugs, PZA is not affected by the use of other antibiotics (Lamont et al. 2020). The effectiveness of PZA depends on the presence of an enzyme called pyrazinamidase (PZase), which is encoded by the pncA gene in M. tuberculosis (Khan et al. 2021). PZA is absorbed by M. tuberculosis through passive diffusion and is then converted into pyrazinoic acid (POA) by PZase, which has antimycobacterial activity. Pyrazinoic acid inhibits the enzyme that involves the synthesis of the bacteria’s fatty acid components, such as mycolic acid and lipid membrane components (Purkan et al. 2024; Mehmood et al. 2019). However, the development of PZA resistance in clinical isolates of M. tuberculosis is often linked to mutations in the pncA gene. These mutations lead to a decrease in PZase activity, which reduces the drug’s effectiveness against TB.

It is not yet clear how the loss of PZase (pyrazinamidase) affects PZA (pyrazinamide) resistance, since clinical isolates of M. tuberculosis that lack the pncA gene are rare. Mutations in the pncA gene, which are predominantly in the form of insertions, deletions, and frameshifts, lead to a decrease in the gene product’s functionality. This decrease is then associated with high levels of resistance to PZA. The pncA mutations in clinical isolates of M. tuberculosis that are resistant to PZA are unique to specific geographical regions (World Health Organization 2023). These mutations are highly diverse, including point mutations, deletions, and insertions (Shi et al. 2022; Tunstall et al. 2021). It is essential to identify the types and positions of pncA mutations in PZA-resistant M. tuberculosis clinical isolates, particularly in the effort to map genetic biomarkers for PZA resistance in these local clinical isolates. Furthermore, identifying pncA mutations is crucial in developing a concept of the mechanism of PZA resistance.

It has been conducted profiling of the pncA gene from several clinical isolates of PZA-resistant M. tuberculosis. These genes have also been cloned into Escherichia coli host cells using the pGemT-easy cloning vector and the pET30a+ expression vector (Hadi et al. 2023; Purkan et al. 2024). One of the reported PZA-resistant clinical isolates is the R1 clinical isolate, where its pncA gene has mutations T41C, G419A, and A535G compared to the PZA-sensitive M. tuberculosis H37RV isolate. The pncA gene mutations in the R1 isolate alter the amino acid residue sequence C14R, R140H, and S179G in its PZase protein (Hadi et al. 2023; Purkan et al. 2024).

Although mutations in the pncA gene of M. tuberculosis R1 have been linked to resistance to the drug PZA, the connection between this drug resistance and the structure and function of its PZase enzyme is not yet fully understood. The relationship between pncA gene mutations and PZA resistance in clinical isolates of M. tuberculosis R1 requires an explanation of the structure of PZase to clarify the enzyme function at the protein level. In this regard, a study was conducted to simulate molecular dynamics to test the stability of the structure from an energy aspect and the changes in chemical interactions between amino acid residues that make up the mutant R1 PZase protein. The structure of the mutant protein will be compared with the wild-type PZase structure from PZA-sensitive clinical isolates of M. tuberculosis. This study presents an integrative structural analysis by combining homology modeling, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics simulations to evaluate the structural and functional differences between the wild-type (WT) and mutant PZase enzymes. Although the R1 mutant has previously been associated with pyrazinamide resistance, this is the first time its precise structural basis for reduced drug binding has been elucidated in detail, which is linked with functional enzyme analysis. Furthermore, the research uniquely focuses on the combined effect of three specific amino acid mutations—Cys14Arg, Arg140His, and Ser179Gly—offering a more comprehensive and realistic model of clinical resistance compared to previous studies that typically analyzed single-point mutations in isolation.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Samples

Two recombinant E. coli BL21 (DE3) isolates were used, each carrying the recombinant plasmids pET-30a-pncA-WT and pET-30a-pncA-R1. pncA-WT is a wild-type gene derived from a pyrazinamide (PZA)-sensitive M. tuberculosis isolate, while pncA-R1 is a mutant gene derived from a PZA-resistant M. tuberculosis clinical isolate. Another bacterium used in this study was an E. coli BL21 (DE3) isolate containing the pET-30a plasmid, which served as a control. The sequence of the mutant PZase was taken from a previous study by Purkan et al. (2024). The crystal structure of the wild-type PZase H37Rv was also downloaded from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) with the code 3PL1.

2.2. Regeneration of recombinant E. coli BL21(DE3) isolate

E. coli BL21 (DE3) containing [pET-30a], [pET-30a-pncA-WT], and [pET-30a-pncA-R1] isolates were each taken as a single colony with a sterile wire to be streaked on solid LB-kanamycin media. The culture was incubated at 37°C for 24 hours (Purkan et al. 2018).

2.3. Inoculum preparation

A single colony of recombinant E. coli BL21 (DE3) was cultured in liquid LB-kanamycin media aseptically, then incubated at 37°C with 150 rpm overnight (16–18 hours) (Purkan et al. 2020; Purkan et al. 2017).

2.4. Expression of PZase

PZase expression was performed by inoculating 1% of recombinant E. coli BL21 (DE3) into 100 mL of sterile LB-kanamycin medium. The culture was incubated at 37°C, 150 rpm for 1–2 hours until OD600 reached 0.4–0.6. Then, 100 μL of 0.003 mM lactose was added for induction, followed by overnight incubation at 16°C, 150 rpm. Cells were harvested by centrifugation (4°C, 5000 rpm, 10 min), washed with sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7), and resuspended in 10 mL of the same buffer. Lysozyme (0.1 mg/mL) was added and incubated at room temperature for 1 hour. Cells were lysed by sonication (50% power, 15 min, 30 s ON/OFF), and the lysate was centrifuged (4°C, 6000 rpm, 20 min) to obtain the cell-free extract. PMSF (1 mM) was added to prevent protein degradation. PZase presence was confirmed by enzyme assay and SDS-PAGE (Purkan et al. 2012).

2.5. SDS-PAGE Analysis

This analysis was carried out using polyacrylamide gel consisting of 5% stacking gel and 12% separating gel. The composition of the 12% separating gel (2 gels) consisted of 4 mL of 30% polyacrylamide; 3.3 mL of distilled water; 2.5 mL of 1.5 M Tris-HCl pH 8.8; 100 μL of 10% SDS; 75 μL of 15% APS; and 12 μL of TEMED. Meanwhile, the composition of the 5% stacking gel (2 gels) consisted of 0.85 mL of 30% polyacrylamide; 3.4 mL of distilled water; 0.625 mL of 1 M Tris-HCl pH 6.8; 50 μL of 10% SDS; 38 μL of 15% APS; and 8 μL of TEMED. The sample was inserted into the gel well and electrophoresis was run at 70 V for 2.5 hours (Purkan et al. 2024).

2.6. Activity test of PZase enzyme

The activity of PZase enzyme was determined based on the modified Wayne assay method [29]. A total of 50 μL of the optimized enzyme production sample was mixed with 500 μL of solution A (2 mM PZA in pH 7.0 sodium phosphate buffer), followed by incubation at 37°C for 30 minutes. After incubation, the reaction was stopped with 50 μL of 20% ferrous ammonium sulfate, followed by the addition of 400 μL of 100 mM cold glycine-HCl buffer (pH 3.4), and the absorbance was measured at 460 nm (A460). The amount of A460 is equivalent to the amount of POA concentration produced (Purkan et al. 2024; Sheen et al. 2009).

2.7. Structural modeling, docking and molecular dynamics simulation

The structural model of the mutant PZase R1 was generated using the SWISS-MODEL server, with the crystal structure of the wild-type PZase (PDB ID: 3PL1) used as a template. The model’s root mean square deviation (RMSD) was calculated by superimposing it onto the 3PL1 structure using the SuperPose server (version 10) (Schwede et al., 2003; Abdjan et al., 2023), and the structure was visualized using PyMOL version 1.3. Docking simulations were performed with AutoDock6 (Brozell et al., 2012; Petrella et al., 2011), using pyrazinamide (PZA) as the substrate. Both the ligand and receptor were treated as rigid bodies during docking to determine the initial coordinates for molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. The MD simulations were conducted using the Amber 16 software package (Case Da et al., 2017) on a PC with an Intel Core i3 processor, 16 GB of RAM, and running Ubuntu 16.04.3. To speed up the simulations, a CUDA-enabled Nvidia GTX 1080Ti GPU with 80 GB of memory was utilized. The binding energy, representing the affinity between the ligand and the PZase structure, was calculated using the MMGBSA.py method (Nickolls et al., 2008; Hayashi et al., 2022).

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

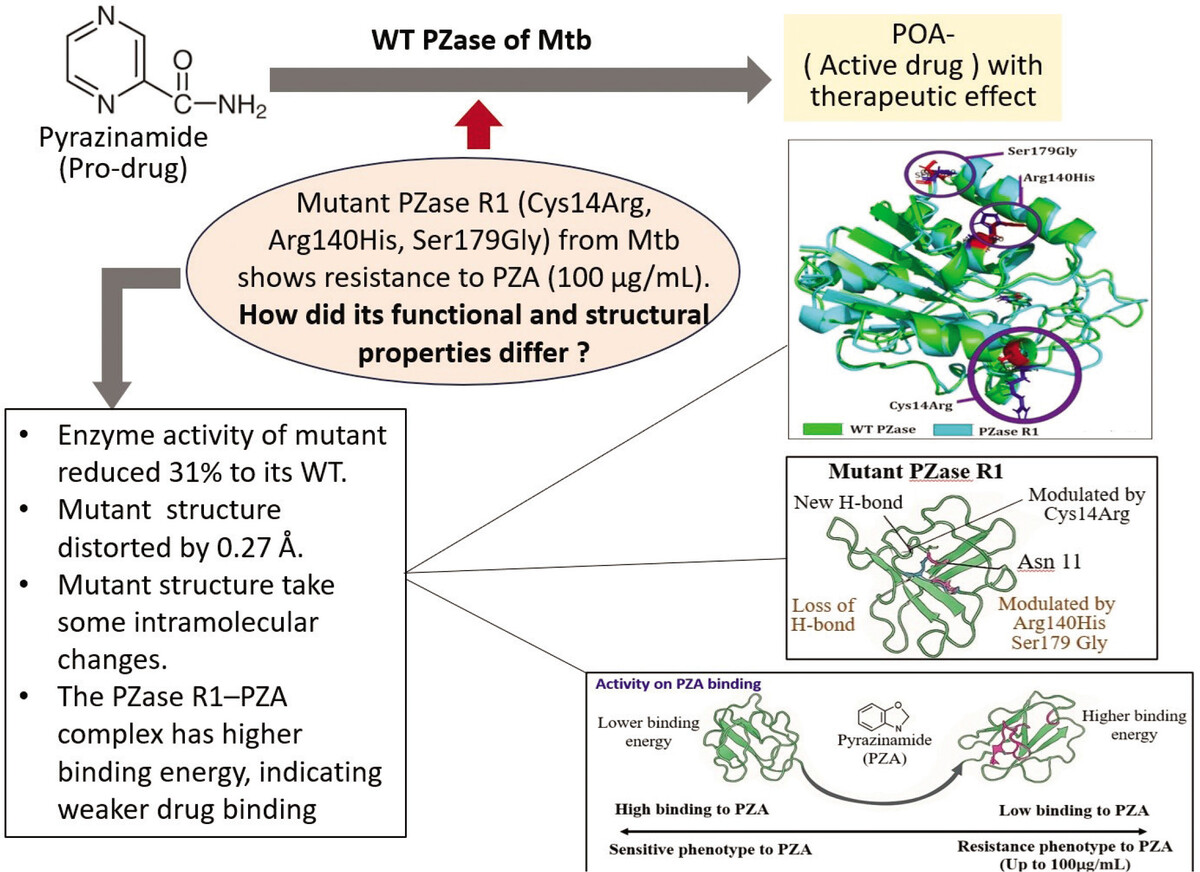

3.1. Rejuvenation of Recombinant E. coli Bacteria

E. coli BL21 (DE3) bacteria containing recombinant plasmids pET30a-pncA-R1, which were samples in the study, were rejuvenated on LB-kanamycin media. These recombinant E. coli BL21 (DE3) bacteria can grow on LB-kanamycin media because they contain recombinant plasmids pET30a-pncA, where the pET30a plasmid carries the genetic marker “kan,” which is responsible for the emergence of the kanamycin resistance phenotype (Figure 1).

3.2. The Expression of pncA into PZase Enzyme

For the expression process, recombinant E. coli BL21 (DE3) [pET30-pncA-R1] and recombinant E. coli BL21 (DE3) [pET30-pncA-WT] were cultured in LB-kanamycin media and inducers were added. The inducer functions to stimulate the continuation of the transcription and translation process of the pncA gene on the pET30a-pncA plasmid into the PZase enzyme protein. The effectiveness of lactose as an inducer in expressing the pncA gene was observed by culturing recombinant E. coli BL21 (DE3) [pET30-pncA-R1] in a culture medium supplemented with lactose. The addition of lactose was carried out when the culture had reached an OD at λ = 600 nm of 0.4–0.6, when the bacterial cells were in the logarithmic phase, meaning the cells were in an active condition, and the culture process was continued overnight (16–18 hours).

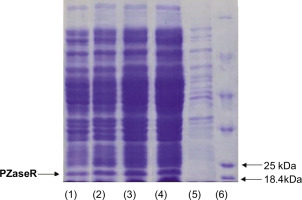

Detection of successful expression was carried out by lysing recombinant E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells that had been harvested with a sonication process to release the PZase enzyme contained in the cells. Cell cavitation due to ultrasonic waves causes the cells to lyse. The supernatant from cell breakdown was analyzed by SDS-PAGE electrophoresis to observe the profile of the resulting protein bands. The results of the analysis of pncA gene expression of recombinant E. coli [pET30-pncA-R1] with SDS-PAGE can be seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2

SDS PAGE electrophoregram of PZase protein resulting from pncA expression. (1) & (2) PZase-WT; (3) & (4) PZase-R2; (5) pET30a control; (6) Marker protein.

The PZase protein band measuring around 22 kDa can be found in the supernatant of recombinant E. coli [pET30a-pncA-WT] and recombinant E. coli [pET30a-pncA-R1] that were cultured at 16°C (150 rpm) with the addition of 0.003 mM lactose (Figure 2, lanes 1–4). The band was not found in the protein expressed by the recombinant E. coli pET30a sample (Figure 2, lane 5). This indicates that the pncA gene can be expressed into PZase well in the presence of lactose as an inducer. This finding is interesting considering that lactose is relatively cheap and easier to obtain.

3.3. Enzyme activity of mutant PZase R1 and its structure model analysis

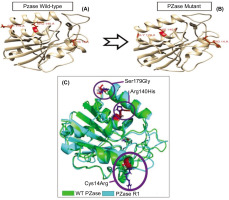

The recombinant PZase R1 mutant exhibited a 31% decrease in enzymatic activity for pyrazinamide (PZA) activation relative to the wild-type enzyme. Triple amino acid substitutions (Cys14Arg, Arg140His, and Ser179Gly) collectively contribute significantly to the diminishing of the catalytic activity in PZase R1. Most mutated pyrazinamidases with variable enzymatic activity showed significant changes in their protein structure (Quiliano et al. 2011). To investigate the structural impact of the triple mutation on PZase R1, computational modeling of the mutant protein was performed. It is needed to provide a structural basis for the observed reduction in the catalytic activity of the mutant enzyme. Based on alignment of the structure model from mutant R1 to wild-type PZase, a shift of 0.27 Å in the mutant R1 structure toward the wild type was observed using Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) analysis (Figure 3). The calculated RMSD value reflects a significant conformational divergence between the R1 mutant and the wild-type PZase.

Figure 3

Structure model of PZase and its alignment which constructed in Swiss-Model and Superpose Server. (A) Wild type PZase structure model, (B) mutant PZase R1 structure model, and (C) Structural alignment product. The structure mutant R1 shift 0.27 Å from its wild type structure.

The triple mutations in the mutated PZase R1, i.e., Cys14Arg, Arg140His, and Ser179Gly, damage some local intramolecular interactions in the original PZase structure and then contribute to the overall deviation in the mutant PZase R1 structure as reflected in its RMSD value. The Cys14Arg substitution leads to the formation of a new hydrogen bond with Asn11, which is not present in the wild type. In contrast, the substitutions Arg140His and Ser179Gly result in the loss of electrostatic and hydrogen interactions, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1

Interaction change in the structural of mutant R1 and wild type PZase.

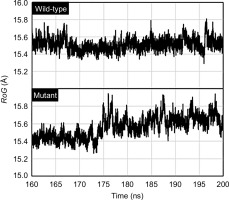

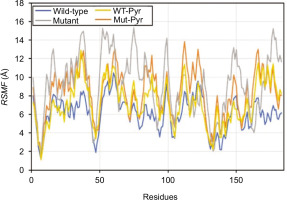

3.4. Flexibility and compactness analysis of mutant PZase R1 structure toward its wild type

The flexibility dynamics of the amino acid residues composing the mutant PZase R1 structure compared to its wild type were observed by root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) analysis. The mutant PZase R1 exhibited a higher RMSF score than the wild type, with values of 9.20 ± 3.21 Å (free form) and 8.40 ± 2.56 Å (with PZA ligand), compared to 6.08 ± 1.85 Å and 7.28 ± 2.33 Å for the wild-type PZase, respectively (Table 2 and Figure 4). A higher RMSF score indicates that the mutant PZase R1, both in its free form and when bound to PZA, is more flexible and structurally less stable than the wild-type PZase.

Figure 4

Residue flexibility of WT and mutant PZase in the RMSF analysis. Peak fluctuation of residues in mutant PZase R1 was seen to be higher than in WT PZase.

Table 2

Flexibility score (RMSF) and Compactness (RoG) mutant and wild type PZase.

| Paramaters | Wild-type PZase | Wild-type PZase + pyrazinamide | Mutant PZase R1 | Mutant PZase R1 + pyrazinamide |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSF (A) | 6.08±1.85 | 7.28±2.33 | 9.20±3.21 | 8.40±2.56 |

| RoG (A) | 15.51±0.07 | 15.27±0.04 | 15.56±0.12 | 15.39± 0.06 |

Meanwhile, the compactness of the mutant PZase R1 structure relative to its wild type was also studied by measuring the radius of gyration (RoG) of both structures. According to this analysis, the RoG values for the mutant PZase R1 structure model were higher than those of the wild type, with values of 15.56 ± 0.12 Å without the PZA ligand and 15.39 ± 0.06 Å with the ligand. In comparison, the wild-type (WT) PZase exhibited RoG values of 15.51 ± 0.07 Å without the ligand and 15.27 ± 0.04 Å with the ligand (Table 2, Figure 5). Higher RoG values in the protein structure indicate that it is less compact, more open, and generally less stable. Therefore, the PZase R1 mutant appears to be more unfolded, less compact, and less stable compared to the wild-type protein.

3.5. The ability to bind pyrazinamide ligand from mutant PZase R1 and WT PZase

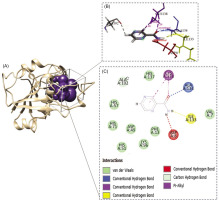

The interaction of pyrazinamidase (PZase) with the pyrazinamide (PZA) ligand occurs at the active site of the enzyme, which is composed of four amino acid residues, namely Asp8, Ile133, Ala134, and Cys138 (Figure 6). Based on the available information, the interaction of the PZA ligand with the structure model of the PZase R1 mutant and wild-type PZase was carried out at the active site, producing the topology of the interaction complex as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 6

Active site of the pyrazinamidase enzyme. (A) PZase receptor, (B) interaction of pyrazinamide (PZA) ligand with PZase, and (C) 2-dimensional diagram of the PZA–PZase interaction. The PZA ligand binds to the PZase enzyme at its active site, which is composed of the amino acid residues Asp8, Ile133, Ala134, and Cys138.

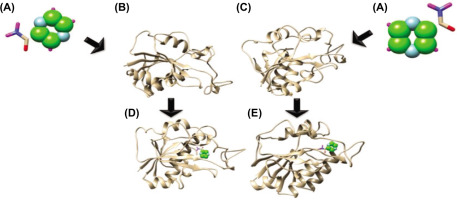

Figure 7

Topology of interaction between PZA ligands and the structure model of mutant and wild-type PZase. (A) The ligand of PZA, (B) the wild-type PZase receptor, (C) the mutant PZase R1 receptor, (D) interaction complex of wild-type PZase–PZA, and (E) interaction complex of mutant PZase R1–PZA.

Determination of the binding energy for the protein–ligand complex was performed by docking and molecular dynamics (MD) simulation analysis. The complex interaction of PZA with wild-type PZase and mutant PZase R1 in the docking analysis resulted in binding energies presented as Grid Energy values of –26.93 kcal/mol and –26.80 kcal/mol, respectively. However, the MD simulation showed the binding energy at ΔG_bind values as –13.96 ± 0.06 kcal/mol for wild-type PZase and –13.16 ± 0.06 kcal/mol for the mutant PZase R1. Both analyses showed consistent results, suggesting that the wild-type PZase binds more strongly to PZA than the mutant PZase R1. The reduced binding ability in the mutant PZase R1 strongly underlies the decreased catalytic activity of the mutant enzyme relative to its wild type. Furthermore, the triple mutations Cys14Arg, Arg140His, and Ser179Gly in the PZase R1 variant can be postulated as the main factor causing the decreased biological function and structural damage of the mutant enzyme. The role of each residue present in the triple mutation of PZase R1 in disrupting its structure–activity relationship is an important investigation for future site-directed mutagenesis studies.

Several mutations have been identified in PZase, contributing to the bacterium’s resistance to therapeutic agents (Dooley et al., 2012). Such mutations modify the enzymatic activity of PZase, thereby reducing the drug’s effectiveness. Some effect mutations to PZase triggered by mutation have been reported in some papers, likely substitution of Asp49Asn, His51Arg, and Gly78Cys, which have a deleterious effect on the metal binding mechanism of PZase. In addition, Asp12Gly, Asp12Ala, Thr135Pro, and Asp136Gly mutations occur close to the active site and weaken the binding of PZA with PZase (Rasool et al. 2019). These other reports underscore the critical role of alterations in amino acid residues in the PZase R1 mutant affecting and diminishing its functional capacity. Correspondingly, Tunstall et al. (2021) investigated the structural and functional consequences of mutations Asp12Ala, Pro54Leu, and His57Pro in PZase. Their analysis revealed that these amino acid substitutions adversely affected protein flexibility and stability, inducing significant structural perturbations that ultimately compromised PZase enzymatic activity (Sheen et al. 2009).

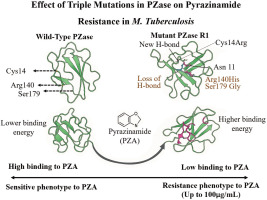

3.6. Effect of Triple Mutations in PZase on Pyrazinamide Resistance in M. tuberculosis

The structural modeling and superimposition of mutant and wild-type PZase revealed a deviation score of 0.27 Å, highlighting significant conformational differences. Analysis of individual mutations showed that the Cys14Arg substitution formed a new hydrogen bond with Asn11, while the Ser179Gly mutation led to the loss of a key intramolecular hydrogen bond with Arg176. Stability assessments through molecular dynamics indicated that the mutant PZase R1 exhibited higher root mean square fluctuation (RMSF), suggesting greater structural instability, and a higher radius of gyration (RoG), reflecting a less compact and more unfolded protein structure. Binding affinity studies demonstrated that the wild-type PZase had a lower binding energy with pyrazinamide, indicating stronger binding, whereas the mutant PZase R1 showed reduced binding capability. Overall, the presence of the triple mutation in PZase R1 significantly impaired the enzyme’s ability to bind pyrazinamide by decreasing activity by 31%, thereby contributing to high-level drug resistance observed in Mycobacterium tuberculosis at concentrations up to 100 μg/mL. Figure 8 represents mutations Cys14Arg, Arg140His, and Ser179Gly increasing protein flexibility and binding energy. These changes reduce pyrazinamide affinity and confer resistance in M. tuberculosis isolate R1.

4. CONCLUSION

The PZase R1 enzyme differs from the wild-type (WT) PZase due to three amino acid substitutions: Cys14Arg, Arg140His, and Ser179Gly. These mutations are linked to pyrazinamide (PZA) resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis at concentrations up to 100 µg/mL. The recombinant mutant PZase R1 has a 31% reduction in activating PZA compared to the wild-type PZase. The mutant enzyme also shows a structural shift in the RMSD score of 0.27 Å, increased flexibility (higher RMSF), and reduced compactness (higher RoG) compared to its wild type. These findings support the significant impact of changes in the flexibility of amino acid residues and the compactness of the mutant structure, further leading to a decrease in its biological function, which in turn contributes to pyrazinamide resistance in M. tuberculosis R1 isolate. Future studies should identify the specific amino acids responsible for disrupting the structure–activity relationship of mutant PZase R1, potentially through site-directed mutagenesis.