1. INTRODUCTION

Functional foods have gained significant attention in recent years due to their potential to provide health benefits beyond basic nutrition. These foods, enriched with bioactive compounds, have been increasingly recognized for their role in preventing and managing chronic diseases, including diabetes mellitus (Khazrai et al., 2014; Kim & Hur, 2021). Diabetes mellitus, particularly type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), remains a major public health challenge, affecting approximately 537 million adults worldwide in 2021, with projections reaching 783 million by 2045 (Khazrai et al., 2014). The rapid increase in diabetes prevalence is largely attributed to sedentary lifestyles, poor dietary habits, and genetic predispositions, necessitating innovative dietary strategies to mitigate its impact. Among various dietary

interventions, plant-based foods rich in dietary fiber, antioxidants, and phytochemicals have demonstrated promising effects in regulating blood sugar levels, enhancing insulin sensitivity, and reducing inflammation (Kim & Hur, 2021).

Legumes have long been recognized as nutritionally rich functional foods that offer metabolic health benefits. Among them, Cajanus cajan (pigeon pea) stands out due to its exceptional nutrient composition and bioactive potential. C. cajan contains a high protein content (20–25%), dietary fiber (10–15%), and essential micronutrients such as calcium, iron, and zinc, all of which play crucial roles in metabolic regulation (S.-E. Yang et al., 2020). In addition to its low glycemic index, the fiber-rich nature of C. cajan contributes to delayed carbohydrate digestion, thereby preventing postprandial glucose spikes. These attributes, coupled with the increasing global adoption of plant-based diets, underscore the importance of pigeon pea as a potential dietary intervention for diabetes management (Kim & Hur, 2021). Beyond its macronutrient profile, C. cajan is also rich in bioactive phytochemicals such as flavonoids, phenolic acids, alkaloids, and tannins, which exhibit antioxidative and antidiabetic properties (S.-E. Yang et al., 2020). However, despite its known nutritional and bioactive potential, the precise molecular mechanisms through which C. cajan exerts its antidiabetic effects remain inadequately understood.

Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 (DPP4) and Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase 1B (PTP1B) are two crucial therapeutic targets in diabetes management. DPP4 plays a critical role in glucose homeostasis by degrading incretin hormones such as glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), which regulate insulin secretion and blood sugar levels (Soare et al., 2020; Wilson et al., 2021). Inhibiting DPP4 prolongs the activity of incretin hormones, leading to improved insulin secretion, reduced glucagon release, and enhanced glycemic control (Dingenouts et al., 2017; Ge et al., 2020; Thottappillil et al., 2022). On the other hand, PTP1B negatively regulates insulin signaling by dephosphorylating the insulin receptor and its substrates, thereby contributing to insulin resistance (Stull et al., 2012; J. Zhang et al., 2015). Inhibition of PTP1B has been shown to enhance insulin sensitivity and improve metabolic outcomes, while also mitigating complications such as diabetic kidney disease and impaired wound healing (Dinh et al., 2012; Legeay et al., 2020). Although synthetic inhibitors targeting these enzymes have been developed, natural inhibitors derived from functional foods provide a promising, less toxic alternative. Notably, studies have reported that C. cajan contains bioactive compounds such as Cajanonic acid A, which has demonstrated inhibitory activity against PTP1B (L. Zhang et al., 2020). However, research on the potential of C. cajan bioactives in inhibiting DPP4 remains limited.

Previous studies have explored the pharmacological properties of plant-derived bioactive compounds in diabetes management. Flavonoids, phenolic acids, and stilbenes from various plant sources have been shown to modulate glucose metabolism by inhibiting key enzymes such as DPP4 and PTP1B (Da Porto et al., 2021; Kim & Giovannucci, 2022). For example, genistein, a flavonoid found in soy and legumes, has been shown to improve insulin sensitivity and reduce oxidative stress (Sarkar et al., 2022), and prevent insulin resistance by modulating cholesterol metabolism (Hermanto et al., 2023). Similarly, naringenin has demonstrated inhibitory effects on α-glucosidase and α-amylase, reducing postprandial glucose levels (Da Porto et al., 2021). Despite these promising findings, limited research has been conducted on the specific bioactive compounds from C. cajan and their interactions with diabetes-related enzymes. While some studies have identified flavonoids and stilbenes in C. cajan (Jiao et al., 2023; Zhao et al., 2023), their direct inhibitory effects on DPP4 and PTP1B remain largely unexplored.

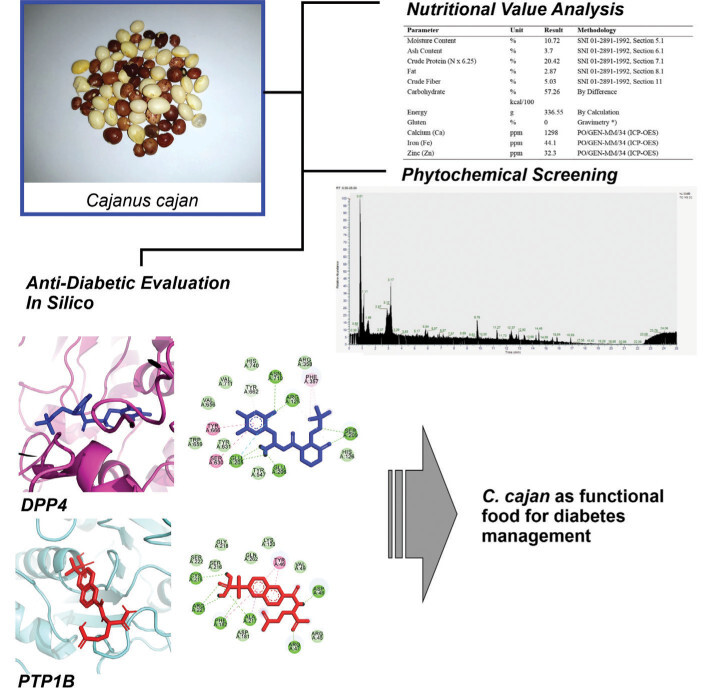

This study comprehensively evaluates C. cajan beans to establish their potential as a functional food for diabetes management. Nutritional analysis (determining macronutrient/micronutrient profiles) integrated with advanced phytochemical profiling using LC-HRMS and computational simulations (investigating molecular interactions of bioactive compounds with DPP4 and PTP1B targets) were employed to scientifically validate this application. The novelty lies in identifying specific C. cajan bioactives with strong inhibitory effects against these key diabetes-related enzymes, thereby supporting its use in dietary interventions for metabolic disorders. Given the global burden of diabetes and the limitations of synthetic drugs, this research aimed to provide a robust scientific foundation for utilizing C. cajan as a natural, sustainable, and accessible functional food. The findings are expected to advance the development of plant-based therapeutic strategies and lay the groundwork for clinical studies and functional food products targeting diabetes.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Sample collection and metabolite extraction

The Cajanus cajan beans used in this study were sourced locally from Madura Island, Indonesia, following the established protocols outlined by Purwanti et al. (Purwanti et al., 2023). The beans were thoroughly cleaned to remove debris and contaminants before being dried at room temperature. The dried beans were subsequently ground into a fine powder to facilitate the extraction of bioactive compounds.

2.2. Extraction of bioactive compounds

The powdered C. cajan beans were subjected to an ethanol-based extraction process to isolate bioactive metabolites. A weight-to-volume ratio of 1:3 was maintained, where the powdered beans were submerged in 96% ethanol and left to soak for 24 hours. Following the extraction period, the ethanol solvent was evaporated using a rotary evaporator, and the remaining extract was freeze-dried to obtain a purified final product. This freeze-dried extract was then utilized for subsequent nutritional, phytochemical, and molecular interaction analyses (Purwanti et al., 2023).

2.3. Nutritional composition analysis

The nutritional composition of C. cajan was analyzed at CV. Akancatani Group laboratories, following the protocols established by the Indonesian National Standard (SNI) 01-2891-1992 for food and beverage products. Macronutrient contents, including moisture, ash, protein, fat, fiber, and carbohydrates, were quantified through proximate analysis. Inductively Coupled Plasma-Optical Emission Spectroscopy (ICP-OES) was employed to determine the mineral content, specifically calcium, iron, and zinc, ensuring precise quantification based on standardized laboratory procedures.

2.4. Phytochemical profiling using LC-HRMS

The metabolomic composition of C. cajan was determined through Liquid Chromatography-High Resolution Mass Spectrometry (LC-HRMS). This technique employed a Thermo Scientific™ Vanquish™ UHPLC system coupled with a Q Exactive™ Hybrid Quadrupole-Orbitrap™ Mass Spectrometer. A reversed-phase liquid chromatography method utilizing a phenyl-hexyl column was implemented, with gradient elution conducted using water and methanol containing 0.1% formic acid. The mass spectrometry analysis was conducted in both positive and negative ionization modes, allowing for accurate detection of metabolites with an error margin below 5 ppm. Identified metabolites were annotated using Compound Discoverer® software, which matched MS/MS fragmentation patterns to reference databases such as mzCloud (Windarsih et al., 2022).

2.5. Molecular docking analysis

To investigate the interaction of C. cajan bioactive compounds with diabetes-related protein targets, molecular docking simulations were performed using AutoDock Vina 1.2.5 integrated into PyRx software (Dallakyan & Olson, 2015; Eberhardt et al., 2021). The three-dimensional protein structures of DPP4 (PDB ID: 5Y7K) and PTP1B (PDB ID: 1BZC) were retrieved from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) and prepared for docking by removing water molecules and pre-attached ligands (Syahraini et al., 2023). Ligand structures were obtained from the PubChem database and were set as flexible molecules, ensuring a comprehensive interaction assessment. The docking grid box was adjusted for each protein according to the binding site of the control molecule toward its corresponding protein receptor (Table 1) (Groves et al., 1998; Lee et al., 2017) to optimize binding site coverage. The binding affinity values of C. cajan phytocompounds were compared against standard inhibitors to determine their potential efficacy. Additionally, the interaction chemistry was examined, including polar and nonpolar interactions, to better understand the binding mechanisms and potential therapeutic applications of C. cajan bioactive compounds.

2.6. Molecular dynamics simulation

Structural and interaction stability simulations were conducted using YASARA software according to the previously established protocols (Hermanto et al., 2022) by applying the AMBER14 force field (Maier et al., 2015). The molecular dynamics simulations were performed under physiological conditions, including a temperature of 310 K, a pH of 7.4, a NaCl concentration of 0.9%, and a water density of 0.997 g/cm3. A cubic simulation box with periodic boundary conditions was employed to mimic realistic biological environments. Each simulation was run for 50 nanoseconds to analyze conformational changes, binding stability, and ligand-protein interactions over time. Key outputs such as Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) and Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) were evaluated to assess the stability and flexibility of the protein-ligand complexes. Hydrogen bond formation was also monitored to determine the persistence of ligand interactions throughout the simulation period (Rohman et al., 2023).

2.7. Pharmacokinetics and toxicity prediction

The compounds identified from molecular docking and dynamics analyses were evaluated for absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) properties using Deep-PK, an online deep learning-based pharmacokinetics and toxicity prediction tool (Myung et al., 2024). Predictions were based on each compound’s SMILES code.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1. Nutritional composition of Cajanus cajan

The proximate analysis of Cajanus cajan bean powder provides crucial insights into its nutritional composition, reinforcing its potential as a functional food for diabetes management. The results indicate that C. cajan possesses a balanced macronutrient profile, comprising moisture (10.72%), ash (3.7%), crude protein (20.42%), fat (2.87%), crude fiber (5.03%), and carbohydrates (57.26%). The energy value was recorded at 336.55 kcal per 100 g, underscoring its potential as a source of sustained energy (Table 2).

Table 2

Nutritional value of C. cajan beans powder according to proximate analysis.

Protein, a vital macronutrient in diabetes management, plays an essential role in insulin response modulation and glycemic control. The 20.42% protein content in C. cajan aligns with previous studies highlighting the high protein concentrations in legumes (Table 2), supporting their inclusion in diabetic diets (S.-E. Yang et al., 2020). Additionally, dietary fiber, which contributes to glycemic control by slowing carbohydrate digestion and absorption (Fujii et al., 2013), was recorded at 5.03%, further establishing C. cajan as a beneficial dietary component for individuals managing diabetes.

Beyond macronutrients, C. cajan also exhibited significant mineral content, including calcium (1298 ppm), iron (44.1 ppm), and zinc (32.3 ppm) (Table 2). These micronutrients are critical for metabolic functions and insulin sensitivity. Zinc, for example, plays a vital role in insulin storage and secretion, while iron is essential for hemoglobin synthesis and glucose utilization (Gargi et al., 2022). Calcium’s role in pancreatic β-cell function (Weiser et al., 2021) further underscores the potential of C. cajan in supporting metabolic health.

3.2. Phytochemical profile and bioactive compounds

The phytochemical analysis of Cajanus cajan extract through LC-HRMS revealed a diverse array of bioactive compounds, predominantly flavonoids, phenolic acids, and fatty acids (Table 3). Identified flavonoids such as genistein, naringenin, and biochanin A are well-documented for their antidiabetic properties. Genistein, for instance, has been reported to enhance insulin sensitivity and regulate glucose metabolism by activating the insulin signaling pathway (Da Porto et al., 2021; Kim & Giovannucci, 2022). Similarly, naringenin functions as an inhibitor of carbohydrate-hydrolyzing enzymes such as α-glucosidase and α-amylase, thereby mitigating postprandial glucose spikes (Da Porto et al., 2021; Sarkar et al., 2022).

Table 3

Phytochemical contents of C. cajan identified by LC-MS/MS.

Additionally, C. cajan exhibited the presence of phenolic acids such as maltol and formononetin, which contribute to antioxidative activity. The high antioxidant content is particularly relevant in diabetes management, as oxidative stress plays a crucial role in the progression of insulin resistance and β-cell dysfunction (Sarkar et al., 2022). The presence of these bioactive compounds reinforces the functional potential of C. cajan as a dietary component in diabetes management.

3.3. Interaction of C. cajan’s bioactive compounds with key target proteins

To further investigate the antidiabetic potential of C. cajan, molecular docking analyses were conducted on two key diabetes-related enzymes: Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 (DPP4) and Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase 1B (PTP1B). These enzymes play critical roles in glucose homeostasis and insulin signaling, making them valuable therapeutic targets (Purwanti et al., 2022).

Among the identified bioactive compounds, diosmetin exhibited the strongest binding affinity toward DPP4 with a docking score of -8.18 kcal/mol, surpassing the standard control (–7.965 kcal/mol). Diosmetin’s interaction with DPP4 suggests its potential as a natural inhibitor that could prolong incretin hormone activity, thereby enhancing insulin secretion and glycemic regulation (Ge et al., 2020). Similarly, genistein demonstrated the highest binding affinity to PTP1B at –8.212 kcal/mol (Table 4), suggesting a mechanism through which C. cajan bioactives could enhance insulin sensitivity and glucose uptake (J. Zhang et al., 2015).

Table 4

Binding affinity of selected compounds from C. cajan with value less than –7 kcal/mol.

Figure 1 illustrates the interactions of screened compounds from Cajanus cajan in comparison to the control inhibitor within the DPP4 catalytic site. The control ligand exhibits strong binding affinity, engaging critical residues across the S1, S2, and S2-ext pockets through hydrogen bonding, π–π stacking, and hydrophobic interactions. Specifically, it forms hydrogen bonds with Arg125 and Glu206 in the S2 pocket, π–π stacking with Phe357 in the S2-ext region, and hydrophobic or aromatic interactions with Tyr662, Tyr666, and Trp659 in the S1 pocket (Lee et al., 2017). Collectively, these interactions block access to the catalytic triad (Ser630, His740, Asp708), effectively inhibiting substrate cleavage.

Figure 1

Visualization of DPP4 residues’ interaction with selected phytochemicals from C. cajan. The left panel displays a whole 3D visualization of the complex of DPP4 with screened phytochemicals along with the control, the middle panel displays ligand conformational position during its interaction with DPP4, and the right panel draws residue–ligand atom chemical interactions. The protein was presented in magenta ribbon, while the ligands were displayed in blue sticks. In the 2D visualization, each circular plate displays a residue of DPP4 with different colors corresponding to different chemical interactions.

In contrast, the flavonoid derivatives naringenin, flindersine, and diosmetin exhibit partial overlap with this binding profile. While their aromatic moieties engage the S1 and S2 pockets through π–π or π–alkyl interactions with Phe357 and Tyr662, their hydrogen-bonding interactions with Arg125 or Glu206 are less consistent. Structural variations, such as hydroxyl or methoxy substitutions, influence binding geometry, leading to reduced polar contacts and weaker hydrophobic packing relative to the control, suggesting lower binding affinity.

The inhibitory potential of DPP4 ligands is largely dictated by their ability to establish hydrogen bonds with Arg125 and Glu205/206 while simultaneously engaging Phe357 or Tyr662 through π-stacking. Ligands that mimic the control inhibitor’s binding mode more closely are expected to exhibit higher affinity, effectively obstructing substrate access to the catalytic triad. Although the test compounds demonstrate moderate inhibitory potential by partially engaging key S1/S2 residues, their limited hydrogen bonding and suboptimal hydrophobic interactions likely result in weaker inhibition. Notably, structural modifications that enhance hydrogen bonding with Arg125 or Glu206 while reinforcing π-stacking with Phe357 could improve their binding efficiency. Such optimizations would better position these flavonoids to sterically hinder enzymatic activity, enhancing their therapeutic potential as DPP4 inhibitors.

At the PTP1B interactions, the control inhibitor exhibits extensive bindings with the PTP1B catalytic site and engages critical residues through hydrogen bonding, π-stacking, and van der Waals interactions. It establishes hydrogen bonds or π-alkyl interactions with Arg221, a key residue for electrostatic stabilization of phosphotyrosine mimics (Groves et al., 1998), while π–π stacking with Phe182 in the WPD loop further stabilizes its binding. Additional interactions with residues in the pTyr recognition loop (Tyr46, Arg47, Asp48, Val49) through polar or van der Waals contacts reinforce its positioning within the binding cleft (Groves et al., 1998) (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Interaction of PTP1B residues with selected C. cajan phytochemicals. (Left) 3D overview of PTP1B (cyan ribbon) complexed with phytochemicals and control (red sticks). (Middle) Ligand binding conformations within the PTP1B active site. (Right) Detailed residue–ligand atomic interactions. (Bottom) 2D representation of PTP1B residues and their specific chemical interactions with ligands.

Similarly, the flavonoid derivatives barpisoflavone A, formononetin, and genistein bind within the catalytic pocket, interacting with Phe182 and Tyr46 via π–π stacking and engaging Arg221 through π-alkyl or hydrogen-bond interactions. However, variations in hydrogen-bond geometry and aromatic ring orientation distinguish their binding modes. While all three compounds occupy the same binding site as the control, differences in hydrogen-bond networks, such as direct interactions with Arg221 or backbone atoms in the pTyr loop, suggest variations in binding affinity (Figure 2). These structural similarities confirm that the natural compounds effectively target the catalytic pocket, engaging residues essential for substrate recognition and inhibition, albeit with subtle conformational distinctions influencing their efficacy.

The inhibitory potency of PTP1B ligands is largely determined by their ability to establish strong interactions with Arg221 and Phe182, which are essential for substrate mimicry and catalytic loop stabilization (Groves et al., 1998). High-affinity inhibitors typically form robust hydrogen bonds with Arg221, facilitating phosphate stabilization, alongside optimal π-stacking with Phe182. The tested compounds exhibit varying degrees of engagement. Some compounds form conventional hydrogen bonds with Arg221 or the pTyr loop backbone, while others rely on hydrophobic or π-interactions. The presence of multiple hydrogen bond types enhances intermolecular interactions, improving complex stability (Panigrahi, 2008).

Compounds with hydroxyl or carbonyl groups positioned to strengthen hydrogen bonding with Arg221, coupled with reinforced π-stacking with Phe182, are predicted to exhibit superior inhibition (Itoh et al., 2019). Conversely, partial engagement of these residues or suboptimal orientation within the hydrophobic pocket near Tyr46 and Phe182 may reduce efficacy. While all three flavonoids demonstrate promising interactions with key catalytic residues, their predicted potencies vary based on interaction strength and geometry. Structural optimizations enhancing hydrogen-bond donor/acceptor placement and π-system complementarity with Phe182 could improve inhibitory activity. Collectively, these findings underscore the potential of Barpisoflavone A, Formononetin, and Genistein as PTP1B inhibitors, with their efficacy modulated by spatial arrangement and interaction multiplicity with key catalytic residues.

In summary, the docking results highlight C. cajan’s potential as a functional food with bioactive compounds that can modulate diabetes-related pathways. These findings are consistent with previous studies demonstrating the inhibitory effects of flavonoids on DPP4 and PTP1B (Thottappillil et al., 2022).

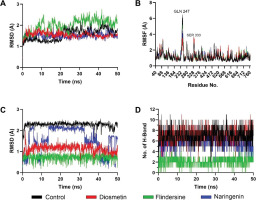

3.4. Structural stability of DPP4 and PTP1B interaction with C. cajan’s bioactive compounds

Molecular dynamics simulations were performed to assess the stability of interactions between C. cajan bioactive compounds and their target enzymes, DPP4 and PTP1B. For DPP4 complexes, backbone root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) analysis revealed that the control inhibitor and naringenin exhibited marginally lower deviations compared to flindersine and diosmetin, indicating enhanced structural stability (Figure 3A). Root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) profiles highlighted transient flexibility at Gln247 and Ser333 across all systems, though these residues were uninvolved in ligand binding (Figure 3B). Ligand-centric RMSD trajectories demonstrated that the control maintained the most stable conformation over the 50 ns simulation, followed by naringenin, while flindersine and diosmetin displayed pronounced conformational shifts (Figure 3C). Hydrogen-bond analysis further corroborated these trends, with the control forming the highest average number of hydrogen bonds with DPP4, followed by naringenin, flindersine, and diosmetin (Figure 3D). These results collectively suggest that the control achieves optimal binding stability, whereas naringenin exhibits moderate retention, and flindersine and diosmetin show reduced affinity due to weaker interactions.

Figure 3

Structural dynamics of DPP4 complexed with control and screened C. cajan phytochemicals. (A) Stability according to RMSD of backbone atoms, (B) stability according to RMSF per residue, (C) ligand conformational stability, and (D) number of formed hydrogen bonds.

The differential stability observed among DPP4-bound ligands aligns with their predicted inhibitory efficacy. The control’s low RMSD, minimal ligand fluctuations, and robust hydrogen-bond network reflect its capacity to occupy the catalytic site with high fidelity, effectively obstructing substrate access (Hermanto et al., 2024). Naringenin’s intermediate performance, marked by slightly elevated RMSD and fewer hydrogen bonds, implies partial engagement with critical residues such as Arg125 and Phe357, likely reducing its potency relative to the control. Conversely, the pronounced conformational shifts and diminished hydrogen bonding in Flindersine and Diosmetin suggest suboptimal complementarity with the S1/S2 pockets, potentially undermining their ability to compete with endogenous substrates. While all compounds remained bound throughout the simulation, the disparities in interaction quality underscore the importance of sustained polar contacts and hydrophobic packing (Raman & Alexander D MacKerell, 2015) for high-affinity DPP4 inhibition.

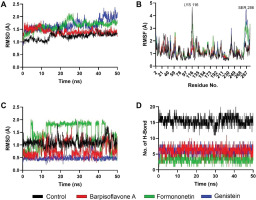

Parallel analyses of PTP1B complexes revealed analogous trends in stability and interaction dynamics. Backbone RMSD values indicated that the control ligand maintained the lowest deviations, followed by Barpisoflavone A and Formononetin, whereas Genistein exhibited greater fluctuations (Figure 4A). RMSF profiles identified heightened flexibility near Lys116 and Ser266 across all systems, though these regions were distal to ligand-binding interfaces (Figure 4B). Ligand-specific RMSD trajectories further differentiated the compounds: the control displayed minimal conformational drift, Barpisoflavone A and Formononetin showed moderate variability, and Genistein underwent significant structural rearrangements (Figure 4C). Hydrogen-bond occupancy mirrored these patterns, with the control forming the most persistent interactions, followed by Barpisoflavone A and Formononetin, while Genistein exhibited the fewest bonds (Figure 4D). These findings highlight the control’s superior capacity to engage the PTP1B active site through a stable network of polar and hydrophobic contacts.

Figure 4

Structural dynamics of PTP1B complexed with control and screened C. cajan’s phytochemicals. (A) Stability according to RMSD of backbone atoms, (B) stability according to RMSF per residue, (C) ligand conformational stability, and (D) number of formed hydrogen bonds.

The stability metrics for PTP1B complexes correlate with their inhibitory potential (Susilo et al., 2024). The control’s minimal backbone and ligand RMSD, coupled with robust hydrogen bonding, reflect its ability to persistently engage catalytic residues such as Arg221 and Phe182, critical for high-affinity inhibition. Barpisoflavone A and Formononetin, with intermediate RMSD and hydrogen-bond profiles, likely maintain partial occupancy of the active site but lack the precision required for optimal interaction geometry. Genistein’s elevated fluctuations and sparse hydrogen bonding suggest a less favorable binding mode, potentially due to inadequate complementarity with the hydrophobic pocket or suboptimal alignment of polar groups. The localized flexibility observed near Lys116 and Ser266, though unrelated to ligand binding, underscores the broader conformational adaptability of PTP1B in response to ligand occupancy. These insights emphasize that sustained hydrogen-bond networks and conformational rigidity are pivotal for achieving potent, long-lasting inhibition (Fatchiyah et al., 2025; Fieulaine et al., 2011; Li et al., 2011) of PTP1B. These results align with previous computational studies suggesting that plant-derived flavonoids exhibit stable and effective interactions with diabetes-related enzymes (Legeay et al., 2020).

The integration of nutritional profiling, phytochemical analysis, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics simulations presents a comprehensive understanding of C. cajan as a functional food with antidiabetic potential. Its rich macronutrient and micronutrient profile supports general metabolic health, while its bioactive compounds exhibit promising interactions with diabetes-related enzymes. The potential mechanisms through which C. cajan may aid in diabetes management include (1) prolonging incretin hormone activity through DPP4 inhibition (Lamont & Drucker, 2008), (2) enhancing insulin sensitivity via PTP1B inhibition [44], and (3) reducing oxidative stress via its flavonoid and phenolic acid content (Nix et al., 2015). These findings provide a compelling argument for the dietary inclusion of C. cajan as part of a holistic diabetes management strategy. Despite these promising findings, more pre-clinicals and further clinical validations are required to translate these effects into human applications.

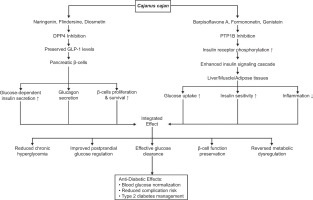

3.5. Molecular mechanisms of anti-diabetic activity of Cajanus cajan flavonoids

Computational analysis reveals that Naringenin, Flindersine, and Diosmetin from C. cajan inhibit DPP4 by binding directly to its active site. Their inhibitory efficacy stems from forming essential hydrogen bonds with catalytic residues Arg125 and Glu205/206, while simultaneously engaging Phe357 or Tyr662 via π-stacking interactions. This precise binding competitively blocks DPP4’s catalytic function, preventing the rapid degradation of incretin hormones like glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) (Soare et al., 2020; Wilson et al., 2021). Consequently, sustained GLP-1 levels enhance glucose-dependent insulin secretion from pancreatic β-cells, suppress glucagon release, and promote β-cell proliferation and survival (Nadkarni et al., 2014; Wenjing et al., 2017). This mechanism directly improves postprandial glucose regulation by optimizing insulin levels during hyperglycemia and contributes to long-term pancreatic function (Figure 5).

Figure 5

Proposed anti-diabetic mechanisms of Cajanus cajan bioactives via DPP4 and PTP1B inhibition. Compounds such as naringenin and diosmetin preserve GLP-1 levels, enhancing β-cell function and insulin secretion. Others, like Barpisoflavone A and formononetin, boost insulin signaling through PTP1B inhibition. Together, these pathways improve glucose uptake, insulin sensitivity, and reduce inflammation, supporting effective glucose clearance and type 2 diabetes management.

Similarly, Barpisoflavone A, Formononetin, and Genistein from C. cajan target the catalytic pocket of PTP1B. Computational studies indicate these flavonoid derivatives bind via π–π stacking interactions with key residues Phe182 and Tyr46, complemented by π-alkyl or hydrogen-bond interactions with Arg221. This binding, potentially competitive or mixed-type, induces conformational changes that diminish PTP1B’s catalytic activity. By inhibiting PTP1B, these flavonoids prevent the dephosphorylation of the activated insulin receptor and its downstream substrates, thereby restoring the insulin signaling cascade (Almasri et al., 2021). This enhances insulin sensitivity and stimulates glucose uptake in insulin-responsive tissues (Ding et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2015), while concurrently mitigating inflammation associated with insulin resistance (Grant et al., 2014). The resulting improvement in cellular glucose clearance effectively reduces chronic hyperglycemia and associated metabolic dysregulation (Shannon et al., 2018) (Figure 5).

While DPP4 and PTP1B inhibition by C. cajan flavonoids (Naringenin, Flindersine, Diosmetin for DPP4; Barpisoflavone A, Formononetin, Genistein for PTP1B) directly addresses insulin secretion and sensitivity, complementary mechanisms involving other enzymes may further contribute to their anti-diabetic profile. Flavonoids frequently inhibit α-glucosidase, an enzyme in the small intestine responsible for carbohydrate digestion (Şöhretoğlu et al., 2018). By delaying glucose absorption, α-glucosidase inhibition reduces postprandial hyperglycemia, an effect synergistic with DPP4 inhibition’s enhancement of incretin-mediated insulin release (Zeng et al., 2016). Additionally, flavonoids like those in C. cajan often activate AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), a cellular energy sensor (Moon, 2024). AMPK activation promotes glucose uptake in skeletal muscle independently of insulin, enhances fatty acid oxidation, and suppresses hepatic gluconeogenesis (Musi, 2006). This pathway complements PTP1B inhibition’s restoration of insulin signaling by providing an alternative route to improve glucose disposal and mitigate insulin resistance in peripheral tissues. Thus, while DPP4 and PTP1B represent primary targets for incretin preservation and insulin sensitization, respectively, concurrent modulation of α-glucosidase and AMPK could provide a multi-faceted mechanistic foundation for the anti-hyperglycemic effects of C. cajan flavonoids, addressing both glucose influx and cellular utilization. Further studies should explore the potential of those flavonoids, including other bioactive compounds in C. cajan, in inhibiting α-glucosidase and AMPK to further comprehend the anti-diabetic mechanism of C. cajan.

3.6. Pharmacokinetics and Toxicity Profile of Potential Compounds

The ADMET analysis of six bioactive compounds from C. cajan revealed pharmacokinetic and toxicity profiles based on prediction probability scores (0–1). Overall, all compounds showed high probabilities of human intestinal absorption (Absorbed: 0.945–0.998), suggesting efficient gastrointestinal uptake. However, probabilities for oral bioavailability at 20% and 50% thresholds varied: Bioavailable (0.464–0.785) and Bioavailable/Non-Bioavailable (0.51–0.777), indicating inconsistent systemic circulation potential. Most compounds were predicted to have short half-lives (Half-Life <3hs: 0.172–0.33). Widespread inhibition probabilities were observed for CYP1A2 (Inhibitor: 0.764–0.99) and CYP3A4 (Inhibitor: 0.765–0.907), highlighting drug-drug interaction risks. Toxicity predictions were mixed: all compounds showed low mutagenic potential (Safe: 0.001–0.456 in AMES) and avian safety (Safe: 0.09–0.288), but high probabilities of hepatotoxicity (Toxic: 0.541–0.766). P-glycoprotein interactions included inhibitors (Inhibitor: 0.52–0.928) and substrates (Substrate: 0.09–0.548), complicating distribution pathways (Table 5).

Table 5

Absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) profiles of six screened C. cajan bioactives.

Diosmetin and Formononetin stood out as promising candidates. Diosmetin had high absorption probability (Absorbed: 0.945) and moderate bioavailability (Bioavailable: 0.533–0.534), though its strong CYP1A2 inhibition probability (Inhibitor: 0.99) requires scrutiny. Formononetin exhibited the highest bioavailability probability (Bioavailable: 0.777) and absorption (Absorbed: 0.998), but its potent P-gp inhibition (Inhibitor: 0.928) raises interaction concerns. In contrast, Genistein showed high carcinogenicity (Toxic: 0.535) and hepatotoxicity (Toxic: 0.766) risks despite moderate absorption (Absorbed: 0.982). Flindersine, while having high 20% bioavailability (Bioavailable: 0.785), was predicted as non-bioavailable at 50% (0.464) and a P-gp inhibitor (Inhibitor: 0.52). Barpisoflavone A and Naringenin displayed intermediate profiles, with Barpisoflavone A showing low mutagenicity (Safe: 0.025) and Naringenin flagged for bee toxicity (Table 5).

The pharmacokinetic profile of C. cajan bioactive presents a compelling case for their integration into functional foods for diabetes management. While these compounds exhibit high absorption (0.945–0.998) and moderate bioavailability (≥0.51), their therapeutic utility is challenged by short systemic half-lives (<3 hours), necessitating repeated meal-time ingestion to sustain antidiabetic effects. However, this kinetic limitation aligns serendipitously with functional food dynamics: frequent, low-dose consumption mimics natural dietary patterns (Butnariu, 2024; Cano-Europa et al., 2012), ensuring transient but targeted inhibition of enzymes (Peddio et al., 2022) like DPP4 and PTP1B during postprandial glucose surges. Crucially, their rapid clearance mitigates risks of prolonged CYP enzyme saturation (Nettleton & Einolf, 2011; Wright et al., 2019) and potential drug-induced liver injury (DILI) (Jain et al., 2013) confining drug interaction windows despite high in silico-predicted inhibition potential. This transient inhibition profile, coupled with delivery within the pigeon pea food matrix, inherently reduces cumulative exposure. The matrix itself, comprising viscous fibers, resistant starches, and proteins, modulates flavonoid release, dampening peak plasma concentrations and physically sequestering compounds to lower hepatotoxicity and genotoxicity risks predicted at higher isolated doses (Bordenave et al., 2014; Y.-D. Yang et al., 2023). While current ADMET simulations suggest potential CYP inhibition and hepatotoxicity at isolated doses, these predictions warrant further refinement via dynamic modeling or in vitro validation to strengthen confidence in translational safety when scaled to dietary exposure contexts.

Further strategies, such as microencapsulation (Yan & Kim, 2024), nanoemulsions (Buddhadev & Garala, 2023), or co-formulation with phase-II enzyme inducers (Qiu et al., 2018), could refine kinetic and safety profiles by prolonging intestinal residence, enhancing hepatic defenses, or sparing doses via permeability improvements. Importantly, the holistic nutrient matrix of pigeon pea amplifies antidiabetic efficacy through complementary pathways: slow starch digestion blunts glycaemic spikes (Copeland, 2020; Kaur & Sandhu, 2010), fermentable fibers modulate gut microbiota and insulin sensitivity (Salamone et al., 2021), and proteins stimulate incretin release (Toffolon et al., 2021). Synergistic interactions with co-existing polyphenols and minerals further enhance flavonoid activity while mitigating oxidative stress linked to DILI. Thus, the short half-life, often a pharmacokinetic drawback, becomes a strategic asset in a food-based context, enabling transient enzymatic targeting without sustained systemic burden. By leveraging the inherent safety of dietary doses, multi-modal nutrient interactions, and formulation innovations, C. cajan flavonoids can be optimized as a sustainable, low-risk functional food, balancing efficacy with minimized ecotoxicity and hepatotoxicity concerns.

4. CONCLUSIONS

C. cajan possesses a robust nutritional profile, including high protein (20.42%), fiber (5.03%), and essential minerals, alongside bioactive flavonoids like diosmetin and genistein. These compounds exhibited potent inhibitory effects on DPP4 (−8.18 kcal/mol) and PTP1B (−8.212 kcal/mol), validated by stable molecular dynamics interactions (RMSD ≤2.5 Å). The findings align with C. cajan’s potential to regulate glucose metabolism through enzyme inhibition and antioxidant activity. However, ADMET analyses indicate hepatotoxicity concerns for isolated compounds, emphasizing the need for formulation within the food matrix to enhance safety. Future studies should prioritize clinical trials to validate efficacy in humans, optimize bioavailability through encapsulation strategies, and explore synergistic effects of C. cajan’s nutrient-phytochemical matrix in holistic dietary interventions. Nevertheless, toxicity study is also recommended before proceeding to the clinical studies.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank AI Center of Universitas Brawijaya for providing access to their computing facilities to perform molecular dynamics analysis. This research was funded by the Ministry of Higher Education, Research, and Technology, Republic of Indonesia, under the Matching Fund Kedaireka project with grant no. 29/E.1/HK.02.02/2023.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest with respect to research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

E.P.: research concept and design, collection and/or assembly of data, writing the article, final approval of the article; F.E.H.: collection and/or assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation, writing the article, final approval of the article; F.R.: collection and/or assembly of data, writing the article, final approval of the article; A.H.H.: writing the article, critical revision of the article, final approval of the article; M.M.N.: critical revision of the article, final approval of the article; T.I.P.: critical revision of the article, final approval of the article; W.P.: critical revision of the article, final approval of the article