1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Global scenario of traditional medicine

Traditional medicine serves a crucial function in healthcare. It has been practiced and used in different forms and modes across the globe. Traditional medicine is known as the “sum total of the knowledge, skill, and practices based on the theories, beliefs, and experiences indigenous to different cultures, whether explicable or not, used in the maintenance of health as well as in the prevention, diagnosis, improvement or treatment of physical and mental illness” (Ansari & Inamdar, 2010; Mukherjee, 2001; WHO, 2024). It is also recognized as complementary or alternative medicine in areas where it has travelled in the recent past and is being practiced, though it was not indigenous to these countries (Akerele, 1987; Jaiswal & Williams, 2017; WHO, 2024).

According to the WHO Global Report 2019, around 88% of nations use the traditional and complementary system, which is around 170 WHO member states (WHO, 2019). The actual number of member states using traditional medicine will be higher, as this report only lists countries having well-defined regulatory regimes, laws, rules, policies, agencies, and programs for traditional and complementary medicine (T&CM). Evidence-based traditional medicine has gained momentum in recent years, and more traditional claims are being validated by globally acceptable scientific data (Butnariu & Bostan, 2011; Shill et al., 2024).

Carrying the historical legacy of traditional medicine, India is at the forefront in the domain of indigenous medicine, with a strong portfolio of regulation and healthcare infrastructure in place for practice, practitioners, and products, for which many proactive steps have been taken.

1.2. Traditional medicine (Ayush) in India

Ayurveda, Yoga, Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha, Sowa-Rigpa, and Homeopathy are officially recognized traditional systems in India (Anonymous, 2024; Rudra et al., 2017). The union government established “The Department of Indian Systems of Medicine and Homeopathy” in March 1995 as a part of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. In 2003, the same department was redesignated as the Department of Ayurveda, Yoga & Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha, and Homeopathy (AYUSH) (Ravishankar & Shukla, 2007). In 2014, the Government of India established a dedicated Ministry of Ayush to focus attention on the overall development of Ayush systems, which works toward strengthening education and research (Anonymous, 2024). According to a recent National Sample Survey Office report, about 95% of rural and 96% of urban respondents are aware of Ayush. Around 46% of rural and 53% of urban individuals used Ayush in the past year for prevention or treatment. Ayush is predominantly used for rejuvenation and preventive measures (NSSO, 2024). The dependence on traditional systems of medicine is expected to increase further due to cultural connectivity as well as affordability (Sundarrajan, 2023). At the global level, the World Health Organization and India have come forward to support and take the lead in experience sharing of the progress in the area of traditional medicine and undertake landmark initiatives for the advancement of traditional medicine.

1.3. WHO and India

As there is a growing interest in Ayush systems at the global level and the WHO traditional medicine strategy encourages member states to generate evidence, India, being the hub of Ayush systems, is taking many initiatives. India has successfully promoted Ayurveda and Yoga as soft skills all over the world by initiatives such as the declaration of the International Day of Yoga by the United Nations, which is June 21. Simultaneously, the availability of data on the safety and efficacy of Ayush systems has developed trust in Ayush systems (Kotecha, 2022). The first WHO Traditional Medicine Global Summit was hosted in India in 2023, showcasing the tie between WHO and India. The summit was organized in conjunction with the G20 health ministerial meeting, under the presidency of India, to showcase the political commitment and evidence-based action on traditional medicine. Various stakeholders, including practitioners, patients, regulators, policymakers, international organizations, academicians, and entrepreneurs, discussed and exchanged ideas, information and opportunities about traditional medicine. The Summit catalyzed global action on traditional medicine, promoting its safe and effective integration into healthcare systems to improve health equity and achieve universal health coverage.

Ready to play a global role in traditional medicine, India has a well-established and dynamic regulatory framework for education, research, and products in Ayush systems. This article will briefly outline the various regulatory mechanisms for practice, research, and development and their enabling provisions in place and also shed light on existing gaps and challenges.

2. METHODOLOGY

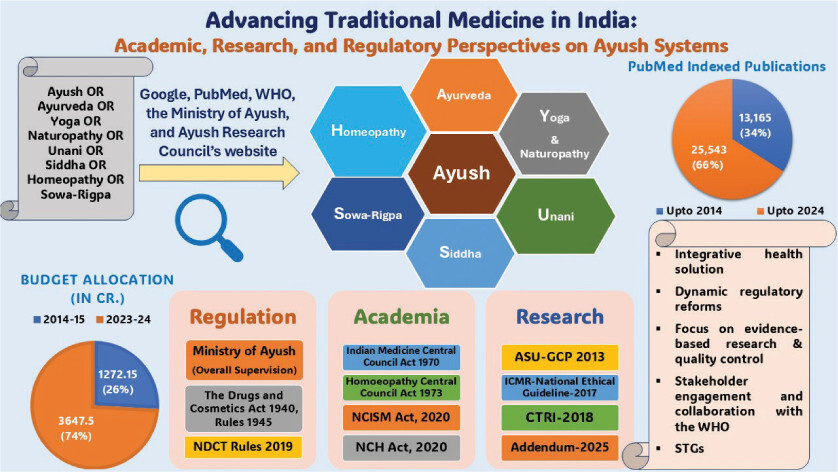

Search string “Ayush OR Ayurveda OR Yoga OR Naturopathy OR Unani OR Siddha OR Homeopathy OR Sowa-Rigpa” was used to retrieve the number of publications in PubMed-indexed journals. The data related to various initiatives and public-funded schemes for the upliftment of traditional medicine in India has been collected by searching Google, PubMed, WHO, the Ministry of Ayush, and the Ayush Research Council’s website.

3. OBSERVATIONS

3.1. Ministry of Ayush

For a developing nation like India, understanding traditional medicine is necessary to understand people’s health-seeking behaviors and attitudes. Traditional medicine has been popular and is still widely believed to be beneficial for primary healthcare needs because it is easy to access, economical, effective, and has few side effects in cases where modern medicine often fails or has nothing to offer. The framework for the research in traditional medicine, education, and its practice has evolved over decades. In 1995, the Department of Indian Medicine and Homeopathy (ISM & H) was established to cater for the traditional system. This department was redesignated as the Department of AYUSH in 2003 and was upgraded to a full-fledged Ministry in 2014 with a mission to promote and flourish Ayush systems of medicine (Sen & Chakraborty, 2017). Since its establishment in 2014, various initiatives have taken traditional Indian systems to the next level with an upward trajectory. The regulations related to education, practice, products, and research have been strengthened to meet the domestic and global requirements.

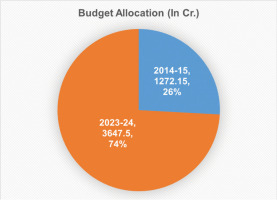

The traditional Indian systems of medicine known as Ayush systems are undergoing various research and development activities through their Research Councils and National Institutes spread across the country. There are well-established regulatory provisions available to regulate and monitor these activities as per standard norms. The Government of India has also provided robust financial funding, and there is almost a three-fold hike in the budget allocation from 1272.15 crores in the year 2014–15 to 3647.5 crores in 2023–24 (Figure 1) (Anonymous, 2024).

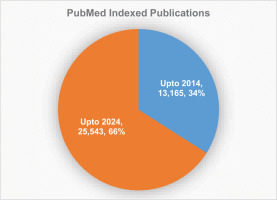

There is a sharp increase in the number of publications from Ayush researchers. The total number of publications related to Ayush on PubMed was 13,165 until 2014, while this number was almost doubled and reached to 25,543 in 2024 (Figure 2).

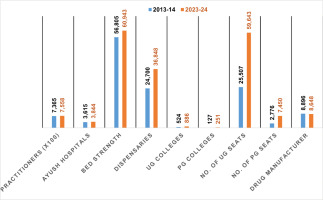

Ayush infrastructure has consistently increased during the last decade in terms of Ayush healthcare centers, healthcare providers, and the number of UG and PG colleges, as depicted in Figure 3 (Anonymous, 2024).

3.2. Regulatory framework for Ayush education and practice

For regulating education and practice in the Indian System of Medicine (ISM) (i.e. Ayurveda, Siddha, and Unani) Central Council of Indian Medicine (CCIM) was set up in 1970, which was the apex organization for regulating ISM. In 2012, the Sowa-Rigpa system was recognized as a traditional Indian system of medicine and was included under CCIM. Later, the National Commission of Indian System of Medicine (NCISM) was constituted, replacing CCIM. Functioning as the statutory body, NCISM was constituted under the NCISM Act, 2020. The NCISM Act came into force in June 2021, and accordingly, the provisions of the Indian Medicine Central Council Act 1970 have been repealed. The central government established a dedicated commission as per the provisions of the NCISM Act. The commission is supported by four autonomous boards, namely, the Board of Ayurveda; the Board of Unani, Siddha, and Sowa-Rigpa; the Board of Ethics and Registration for Indian System of Medicine; and the Medical Assessment and Rating Board for Indian System of Medicine. The main objectives of this commission is “to improve access to quality and affordable Ayurveda, Unani, Siddha, and Sowa-Rigpa (AUS&SR) medical education; to ensure availability of adequate and high quality AUS&SR medical professionals pan India, to promote equitable and universal healthcare that encourages community health perspective and makes services of AUS&SR medical professionals accessible to all the citizens; to encourage medical professionals to adopt latest medical research in their work and to contribute to research; to objectively assess and rate medical institutions periodically in a transparent manner; to maintain a National AUS&SR medical register for India; and to enforce high ethical standards in all aspects of AUS&SR medical services” (NCISM, 2024). NCISM published a regulatory framework for Minimum Standards of Undergraduate Ayurveda Education, Unani Education, Siddha Education, and Sowa-Rigpa Education in 2022. For Homeopathy, a similar exercise has been done by establishing the National Commission for Homeopathy to bring quality in education by formulating policies and guidelines and regulating under the National Commission for Homeopathy Act (NCH, 2024). These bodies are engaged in setting standards and quality assurance in education and practice.

3.3. Regulations for Ayush products

The Ayush products are regulated through a central act, the Drugs and Cosmetics Act (DCA) 1940 and Rules thereunder (1945), and subsequent amendments. Rules 85-A to I and Rules 151 to 159 of this Act provide necessary provisions for the licensing, manufacturing, and sale of Ayurveda, Siddha, and Unani (ASU) drugs. DCA also provides provisions for the quality and safety of ASU medicines being manufactured within the country.

The main objective of DCA-1940 is to control the import, production, and dispersal of drugs in the country. It contains various chapters, rules, and schedules, whereas Chapter IV A is dedicated to Ayush systems. Earlier, for clinical research, Schedule Y of DCA dealt with clinical research in India (Anonymous, 2016). The government revised Schedule Y of the DCA in an effort toward harmonizing with the WHO and ICH clinical trial guidelines, which are based on the “Declaration of Helsinki.” It contained standard formats for clinical trial–related documents, including trial protocols, consent forms, standard operating guidelines for the constitution and functioning of ethics committees or institutional review boards, standard formats for approval, template for reporting serious adverse events. Section 7 of these guidelines elaborates on comprehensively conducting clinical trials, and recommendations have been provided for investigator-initiated clinical trials, academic or student research, multicenter trials or community trials, or traditional systems of medicine, adopting new technologies in clinical research (Gogtay et al., 2017; Imran et al., 2013).

The Indian Government announced new drug and clinical trial (NDCT) rules on March 19, 2019, including 13 chapters and 08 schedules, which have superseded the Part XA and Schedule-Y of the D & C Rules, 1945 (Anonymous, 2019). NDCT is designed to streamline the regulations and facilitate clinical research in India with full adherence to ethical practices. The updated regulations include guidelines for fostering clinical research and for complex topics such as orphan drugs (for rare diseases), post-trial access of drugs to participants, and provision of a presubmission meeting with the sponsor (Annapurna & Rao, 2020).

In July 2022, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, published the draft of the New Drugs, Medical Devices and Cosmetics Bill, 2022. The government asked for opinions from various stakeholders. In view of the advancement of technology and the emerging requirements of the market, this draft bill is designed to replace the old Drugs and Cosmetics Act of 1940. There are provisions for constituting the Drug Technical Advisory Board, Drugs, Medical Devices and Cosmetics Consultative Committee and Scientific Research Board for the respective systems in the proposed bill. These statutory committees and boards will support and advise the regulatory authority on the scientific matters related to drugs, devices, and other related subjects (Anonymous, 2022).

3.4. Ayush research and relevant guidelines

A robust research infrastructure is in place in India, which follows a set of guidelines and is well-regulated in the country.

3.4.1. Establishment of Research Councils and National Institutes for Ayush Systems of Medicine

The Ministry of Ayush has dedicated 5 Research Councils and 15 National Institutes to carry out various research programs. The research is also carried out in collaborative and EMR mode with premium institutes or organizations on national priority areas. These organizations or institutes are also engaged in carrying out clinical research activities under their research programs (Ministry of Ayush, 2025).

In India, clinical trials are regulated and approved by the Central Drugs Standard Control Organization (CDSCO), and the Drugs Controller General of India (DCGI) is the final regulatory authority. CDSCO is also engaged in conducting inspections of trial sites, approval of novel drugs, standardization of drugs, and controlling import and manufacturing facilities. Health being a state subject, CDSCO coordinates with the state licensing authorities to uniformly implement the provisions of DCA (Gogtay et al., 2017). Ayush vertical was established in the CDSCO in February 2018 to oversee the regulation of ASU&H drugs at the national level. The major function of Ayush vertical is to deal with the provisions of DCA, 1940 and rules thereunder, and related issues (Anonymous, 2024).

3.4.2. National Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical and Health Research Involving Human Participants, 2017

The Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) is the apex body of India, responsible for constructing, coordinating, and advancing biomedical research in India. ICMR has set a series of guidelines, the most recent was in 2017. Also, with the passage of time, various new sections have been added, such as “Vulnerability, Public Health Research, Responsible Conduct of Research, Biobanking and Datasets, Social and Behavioral Sciences Research for Health, Informed Consent Process, Biological Materials, and Research during Humanitarian Emergencies and Disasters.” Notably, a few new subsections, like sexual minorities, multicentric studies, and research, are also included. In general, these guidelines are taken into account for ethical review, conducting clinical research, and the applicability of social, biomedical, and behavioral science research in human participants for their biological material and data (Behera et al., 2019; Mathur, 2019). A “Policy Statement on the Ethical Conduct of Controlled Human Infection Studies” in India 2023 was published by ICMR (2023a) and “Ethical Guidelines for Application of Artificial Intelligence in Biomedical Research and Healthcare” (2023b). These guidelines are publicly available on the ICMR website under ICMR ethical guidelines.

3.4.3. Good Clinical Practice Guidelines for Clinical Trials in ASU (GCP-ASU)

The Drugs and Cosmetics Act, 1940 and Rules do not contain clear provisions for the clinical trials of Ayush drugs. The need for dedicated guidelines for clinical revalidation of ASU systems was felt for wider acceptance and global recognition of these systems (Patwardhan, 2011). For the establishment of effectiveness for licensing of patent or proprietary ASU medicine, guidelines for Good Clinical Practice (GCP) were needed, especially after August 2010, when Drug & Cosmetics Rule 158 B was introduced. GCP Guidelines for the conduct of clinical trials on ASU medicines were published by the Ministry of Ayush. Protection of the rights of trial participants and their safety is the fundamental principle of GCP guidelines for ASU medicine. These guidelines specify the criteria for conducting clinical trials on ASU drugs as well as the obligations of sponsors, investigators, trial monitors, and so on. The objective of the guidelines was to instill a culture of performing ASU-based clinical trials in India according to the required scientific standards and well-designed methods to obtain scientifically valid and reliable data. ASU-GCP guidelines emphasized that clinical trial data are recorded, analyzed, and reported with rigorous methodology. Strict compliance with ASU-GCP guidelines will enable the mutual acceptance of data between national and international organizations. Overall, the guidelines adopt CDSCO’s core principles for engaging in GCP, although with a tailored approach to cope with ASU principles and treatment methodologies (Anonymous, 2013).

3.4.4. Clinical Trials Registry of India

Clinical trials, including those in Ayush systems, are registered in a dedicated portal, which was made a mandate by DCGI in the year 2009 that clinical trials shall be registered at the Clinical Trials Registry – India (CTRI) to maintain transparency, accountability, and convenience (Pandey et al., 2008). It is an open online clinical trial registration platform for trials conducted in India and is mandatory for Ayush clinical trials as well (James et al., 2015; Rao et al., 2020; Yadav et al., 2011). With effect from 2018, the CTRI proceeded with the registration of prospective trials and registered only those trials where patient enrolment had not been initiated (Bhapkar et al., 2022). It applied to all Ayush submissions for registration, including academic dissertations, clinical studies, post-market surveillance, and bioavailability and bioequivalence studies.

A study was done to examine the data on clinical studies from 2007 to 2016 registered at the CTRI, to evaluate the clinical research landscape over 10 years. According to their report, the number of studies increased steadily over time, from 31 in 2007 to 589 in 2016, with 1130 being the highest in 2015 (as of June 22, 2016). Interventional trials were more when compared to bioavailability or bioequivalence and observational studies. Studies funded by the pharmaceutical industry were more than any other kind of sponsorship. Nonetheless, the number of clinical studies funded by the pharmaceutical sector continued to decline, although the registration of postgraduate theses and investigator-sponsored studies increased (Bhide et al., 2016).

3.4.5. Nonclinical toxicity evaluation

The requirement for non-clinical toxicity data for Ayush products is mentioned in the Drugs and Cosmetics Act (1940) and Rules (1945). Nonclinical (or preclinical) toxicity evaluation involves experimentation on laboratory animals, which is highly regulated worldwide. The Breeding of and Experiments on Animals (Control & Supervision) Rules of 1998, 2001, and 2006, which were formed under the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act, 1960, govern animal experimentation in biomedical research and education in India. The animal ethics are governed by the Committee for the Control and Supervision of Experiments on Animals (CCSEA). Establishments are required to follow the Rules and Guidelines laid down by CCSEA. The Secretariat of the CCSEA has published its guidelines from time to time, intending to guide its work. A compendium was published in 2018, in which various guidelines issued by the CCSEA for experimentation on animals, with the welfare and well-being of animals, were compiled. CCSEA guidelines are aimed to ensure ethical and humane treatment of animals before, during and after experimentation and to refine the research protocols to minimize the discomfort and suffering of laboratory animals (Anonymous, 2018). Ayush-related nonclinical testing requires full adherence to the prevailing requirement for ethical care of laboratory animals as per CCSEA.

3.5. Research in the Ayush sector during the COVID-19 pandemic

COVID-19 was a global challenge to combat. The Ministry of Ayush took various initiatives to facilitate the research work during those difficult times. An interdisciplinary Ayush Research and Development Task Force was constituted, comprising senior scientists and experts from institutes such as ICMR, AIIMS, CSIR, and Ayush Research Councils. The task force, after a series of consultative processes, developed research protocols for Ayush interventions, a comprehensive document for researching COVID-19. A project monitoring unit was in place to monitor all activities of the Research Councils and the National Institutes under the Ministry of Ayush. A central ethics committee was set up to ensure ethics compliance while conducting the study, and a safety monitoring board was assigned to look after critical data. The concept of data safety and evidence was applied to traditional medicine more rigorously during the COVID-19 and several interventional studies on Ayush formulations were undertaken (Husain, 2021; Khan et al., 2021).

During COVID-19, around 126 studies were initiated involving 152 centers throughout India to identify management strategies for COVID-19 symptoms under various research organizations and the Institutes of Ayush. It includes 42 studies with a prophylactic approach, 40 interventional trials, 22 preclinical or experimental research, 11 observational studies, 1 systematic review, 8 surveys and 2 monographs. 26 Studies were from Homeopathy, 66 from Ayurveda, 13 from Siddha, 8 from Unani discipline, and 13 studies belong to Yoga & Naturopathy. Overall, 10 manuscripts have been published out of 90 completed studies (PIB, 2021). For post-COVID management, Ayush sector offered preventative, supportive, and rehabilitative treatment (Patwardhan & Sarwal, 2021; Sugin et al., 2024).

3.6. Collaboration with World Health Organization (WHO)

The Ministry of Ayush collaborated with the World Health Organization and carried out various futuristic initiatives. WHO has published benchmarks for training and practice in Ayurveda (WHO, 2022a) and Unani medicine (WHO, 2022b). These benchmarks define the minimum requirements or criteria for providing training and establishing practice in Ayurveda and Unani medicine in WHO Member States. This document describes the minimum technical requirements for quality assurance and regulation of practice in these systems of medicine. WHO has also published International Terminologies in Ayurveda (WHO, 2023a), Unani (WHO, 2023b), and Siddha (WHO, 2023c). These are essential tools for integrating Ayurveda, Unani, and Siddha into health systems and also support international collaboration and cooperation in research and the exchange of information and ideas. Ministry of Ayush has also contributed to the inclusion of ASU in the ICD-11 TM2 chapter. In recognition of these efforts, WHO has established GCTM in Gujarat with the support of 250 million US Dollars from the Government of India, with an aim to achieve the goal of health for people and the planet by way of harnessing the potential of traditional systems of medicine through advanced science and technology.

In addition, India, during its G-20 presidency in the year 2023, organized a traditional medicine global summit, which was organized jointly by the WHO and the Ministry of Ayush to reaffirm its commitment to health and well-being by Traditional, Complementary and Integrative Medicine (TCIM). The theme highlighted the essence of India, “One Earth, One Family, and One Future,” and also, for the first time in the G-20 New Delhi Leaders’ declaration, TCIM was factored. It refers to evidence-based interventions, international collaborations, a healthy diet, promotion of a healthy lifestyle and improved access to mental health and clinical research. This provided a strong uplift to traditional medicine at the global level (Tillu & Chaturvedi, 2023).

3.7. Other noteworthy initiatives

3.7.1. Protection of traditional health knowledge

Erstwhile, the Department of Ayush, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare and the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), and the Ministry of Science and Technology, collaborated in 2001 and formed “Traditional Knowledge Digital Library” (TKDL), which is a digital database on traditional medicine, including information on medicinal herbs and their formulations mentioned in traditional systems. The objective of the TKDL database is to prohibit the patenting and misappropriation of indigenous knowledge (Fredriksson, 2023) and to safeguard ancient and traditional knowledge from exploitation through any unethical means. The major activity of TKDL is to scientifically encrypt the classical texts of Ayush systems into a systematic digital database (Muthappan et al., 2022). Presently, more than 4,54,000 formulations and/or practices of Ayush systems have been transcribed into the TKDL database (Anonymous, 2025a; Javed et al., 2020).

3.7.2. Digital initiatives

The Ministry of Ayush embraced extensive digitalization during the past decade. Muthappan et al. (2022) have collated these digital initiatives and reported that under the health information system, Ayush hospital management information system (A-HMIS), Ayush Suraksha, e-Aushadhi, e-Charak, Triskandha Kosha, National Ayush Morbidity, and Standardized Terminologies Electronic Portal (NAMASTE), and SiddAR APP have been implemented. Research database or digital library includes Ayush research portal, TKDL, DHARA, e-CHLAS, Research Management Information system (RMIS), e-Granthasamuccaya and Ayush Sanjivani App. Information, education and communication initiatives include Siddha-NIS App, Yoga locator, and Naturopathy-NIN App. Under academia, Ayurveda e-learning and Ayurvedic Inheritance of India were developed. Unani mobile apps on “know your temperament,” single drugs, common home remedies, compound formulations and standard treatment guidelines have been launched by CCRUM (Anonymous, 2025b).

4. DISCUSSION

Traditional medicine continues to play a pivotal role in global healthcare delivery. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), approximately 88% of countries worldwide report the use of traditional and complementary medicine within their health systems (WHO, 2019). India, with its centuries-old legacy, stands as a frontrunner in promoting and integrating traditional medicine into mainstream healthcare. The establishment of a dedicated Ministry of Ayush in 2014 marked a transformative milestone, reflecting the government’s strategic commitment to advancing Ayush systems both nationally and globally.

Over the past decade, India has undertaken several initiatives to modernize and mainstream Ayush systems, focusing on evidence-based practice and integrative healthcare models. The academic infrastructure for Ayush has undergone significant reforms, expanding in both scale and quality under the leadership of regulatory bodies such as the National Commission for Indian System of Medicine (NCISM) and the National Commission for Homeopathy (NCH). These reforms have resulted in enhanced educational standards, research capacity, and clinical service delivery.

The Ayush industry has also shown remarkable progress by adopting state-of-the-art technologies, improving manufacturing processes, and embracing global quality standards. This shift has helped enhance public trust in Ayush products, making them more acceptable both domestically and internationally.

A key feature of the Indian Ayush regulatory framework is its alignment with international guidelines, ensuring that preclinical and clinical research in traditional medicine adheres to globally accepted standards for quality, safety, and efficacy (Anonymous, 2013). Unlike many conventional regulatory systems, India’s framework incorporates special provisions that recognize the unique and holistic nature of Ayush formulations, enabling the preservation of traditional knowledge while integrating scientific rigor.

Importantly, the framework emphasizes participant rights and safety, adhering to principles of Good Clinical Practice (GCP), confidentiality, and ethical research conduct. The Ministry of Ayush has played a proactive role in facilitating and funding research, fostering both national and international collaborations to expand the evidence base for Ayush systems (Ministry of Ayush, 2025). This has led to the development of standard treatment protocols, research methodologies, and clinical trial guidelines specifically tailored for Ayush interventions.

Another hallmark achievement is the dynamic and evolving nature of the regulatory process, which remains responsive to emerging scientific and technological advancements. The Ministry’s structured approach to clinical trial design, registration, monitoring, and reporting has notably enhanced the credibility and reproducibility of Ayush research outcomes.

A globally significant development is the establishment of the WHO Global Center for Traditional Medicine (GCTM) in India, which serves as a global knowledge hub for research, policy development, and evidence generation in traditional medicine systems. This reflects India’s emerging role as a leader in global traditional medicine governance and policy.

Further, the WHO, in collaboration with the Ministry of Ayush, has contributed to standardizing terminologies, developing benchmarks for practice, and harmonizing training standards across Ayurveda, Siddha, and Unani systems. This aligns with global efforts to integrate traditional medicine into Universal Health Coverage (UHC) goals.

India has also implemented a robust regulatory framework for Ayush practice, education, practitioners, and products, supported by mechanisms for quality control, pharmacovigilance, and post-marketing surveillance. National policies, such as the National Health Policy (2017) and the earlier Indian Systems of Medicine and Homeopathy Policy (2002), underscore the government’s ongoing commitment to Ayush development.

However, challenges remain. While the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) provides guidelines for clinical trials, there is a pressing need for customized regulatory frameworks that address the unique attributes of Ayush therapies, especially regarding trial design, outcome measures, and placebo controls. Developing a dedicated National Ayush Policy could further consolidate and streamline regulatory and developmental efforts.

There is also growing global interest in integrative health approaches, where evidence-based traditional medicine is combined with modern healthcare practices. This trend presents an opportunity for India to showcase Ayush as a cost-effective, culturally accepted, and scientifically validated complement to conventional healthcare.

Significantly, the increased government investment in the Ayush sector has led to improved research capabilities, expanded healthcare facilities, and a rise in the number of trained professionals to meet the growing demand for Ayush services. The quality, scale, and scope of research and service delivery have improved substantially, meeting standards set by national and international regulatory bodies.

To fully harness the potential of Ayush systems, awareness and capacity-building among key stakeholders—researchers, clinicians, policymakers, and the public—are crucial. Enhancing scientific documentation, improving the dissemination of research outcomes, and fostering cross-sector collaborations will further strengthen India’s leadership role in traditional medicine globally.

5. CRITICAL EVALUATION OF EVIDENCE

While significant progress has been made in generating scientific evidence on the safety and efficacy of Ayush interventions, several limitations persist within the existing body of research. Many clinical studies conducted on Ayush formulations and therapies suffer from small sample sizes, lack of multicentric trial designs, inadequate randomization, and absence of long-term follow-up data. These methodological shortcomings limit the generalizability and reproducibility of findings. Additionally, variability in dosage forms, differences in raw material quality, and lack of standardization in manufacturing practices often introduce inconsistencies that may affect the observed therapeutic effects.

Furthermore, the inherent complexity and individualized nature of traditional medicine pose challenges in designing placebo-controlled and double-blind studies, leading to potential biases in reported outcomes. Cultural factors, patient expectations, and practitioner expertise also play a significant role in influencing study results but are often underreported or uncontrolled in published literature.

It is important to recognize these limitations while interpreting the available evidence. Future research should emphasize rigorous clinical trial designs, larger sample sizes, validated outcome measures, and better reporting standards that align with CONSORT and GCP guidelines adapted for traditional medicine systems. Addressing these issues is essential to strengthening the scientific credibility and global acceptance of Ayush interventions.

6. CONCLUSION

India’s regulatory framework for Ayush systems is both comprehensive and dynamic, aimed at ensuring the safety, efficacy, and quality of traditional medicine practices and products. The establishment of the dedicated Ministry of Ayush in 2014, coupled with increased government funding, has been a transformative step toward the structured promotion, regulation, and scientific validation of these systems. This has resulted in enhanced research capacity, quality control measures, and wider acceptance of Ayush both nationally and globally.

Importantly, the framework reflects a balanced and integrative approach, respecting the foundations of traditional knowledge while incorporating modern scientific methodologies for quality assurance and evidence generation. This dual focus is critical for advancing Ayush systems and ensuring their sustainable integration into the mainstream healthcare sector.

However, the rising global shift toward integrative health approaches presents new regulatory and research challenges. There is a growing need for more stringent, Ayush-specific clinical guidelines, improved pharmacovigilance systems, and robust clinical data to strengthen the global credibility and acceptance of Ayush interventions.

One of the major challenges for integrative health solutions is the lack of harmonization of treatment guidelines, which has gained the attention of various stakeholders and regulatory agencies, and efforts are being made toward the development of standard treatment guidelines for various disease conditions.

Moving forward, continuous regulatory reforms, greater investment in evidence-based research, and enhanced stakeholder engagement will be essential for addressing these challenges and for positioning India as a global leader in traditional and integrative healthcare.

7. LIMITATION OF THE STUDY

The major limitation of the present study is that it is focused on the status and growth of traditional medicine recognized in India. Traditional systems prevalent in other parts of the world, such as the traditional Chinese Medicine, the Japanese Kampo medicine, and the African traditional medicines, were not included under the scope of this review.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would like to thank the Vice Chancellor, Galgotias University, and the Director General, CCRUM. Authors also acknowledge the financial support by Galgotias University provided to S.R.C. as seed grant (Ref. No. GU/R&D/SF/001/2024-25).

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

G.J. contributed to the conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, and investigation of the work, wrote and edited the manuscript. M.S.S.D. provided inputs to improve the manuscript’s quality. S.R.C. performed overall supervision, project administration, and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final article.