1. INTRODUCTION

Lactiplantibacillus strains belong to the LAB group, which are ubiquitous microorganisms that colonize the environmental biotopes of many human cavities, such as the intestines and vaginal tract. In addition, they make a major contribution to the microbial flora balance of these cavities through their secretion of various molecules, notably organic acids (Leonov et al. 2023). However, some of them also have beneficial properties, allowing them to be used as a treatment or as a probiotic. Probiotics are beneficial microorganisms when consumed in sufficient quantities. They are currently employed to treat or prevent a few diseases, primarily diarrhea caused by antibiotics and inflammatory bowel disorders (Corsello et al. 2024). Since they are considered generally regarded as safe (GRAS) and have widely recognized functional qualities, LAB are microorganisms that are commonly utilized as probiotics. Multiple health benefits, including anti-inflammatory, anti-obesity, anticancer, antidiabetic, and hypocholesterolemic effects, have been shown to be conferred by their consumption. In order to give these positive health effects, probiotic strains have to pass through the intestine in a viable physiological state. Although it is widely accepted and approved that many LAB strains have probiotic properties, more research is needed to examine the probiotic qualities of original LAB strains possessing particular health advantages as well as higher probiotic qualities than those currently available (Papadimitriou et al. 2015). Furthermore, it is critical to test new strains because of the growing market demand for probiotics.

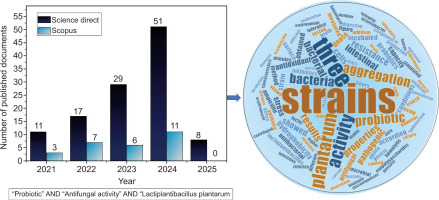

Some selection requirements need to be satisfied before using LAB strains as a probiotic. A bacterial strain that qualifies as probiotic must first tolerate the gastrointestinal tract conditions and colonize the intestines. It must then be resistant to the enzymes in saliva, able to endure the acidic environment of the stomach, and resist the bile and pancreatic fluid in the intestine. In addition, the probiotic LAB species should be able to bind to the cells of the intestine, permitting potential colonization of the intestines; therefore, characteristics of the cell surface, such as hydrophobicity, auto- and co-aggregation, are necessary for colonization. To avoid diseases induced by enteric pathogens, the probiotic strains need to have an anti-pathogenic effect (Amirsaidova et al. 2024). Furthermore, it is necessary to assess strain safety standards, such as the lack of resistance to antibiotics or recognized virulence properties, and it also needs to have other functional characteristics, like the production of beneficial compounds like exopolysaccharides and antioxidant activity. Figure 1 presents the bibliometric analysis of the scientific literature on the antifungal and probiotic activity of Lactobacillus plantarum (Lp. plantarum), and shows that there is a growing interest, reflected in the number of publications, which increased from 11 in 2021 to 51 in 2024 for Science Direct, and from 3 in 2021 to 11 in 2024 on Scopus.

At the start of 2025, when this bibliometric research was carried out, there were only eight publications on Science Direct and none on Scopus. Textual analysis of the literature shows that the words “probiotic,” “plantarum,” “strains,” “bacteria,” and “aggregation” are dominant (Figure 1).

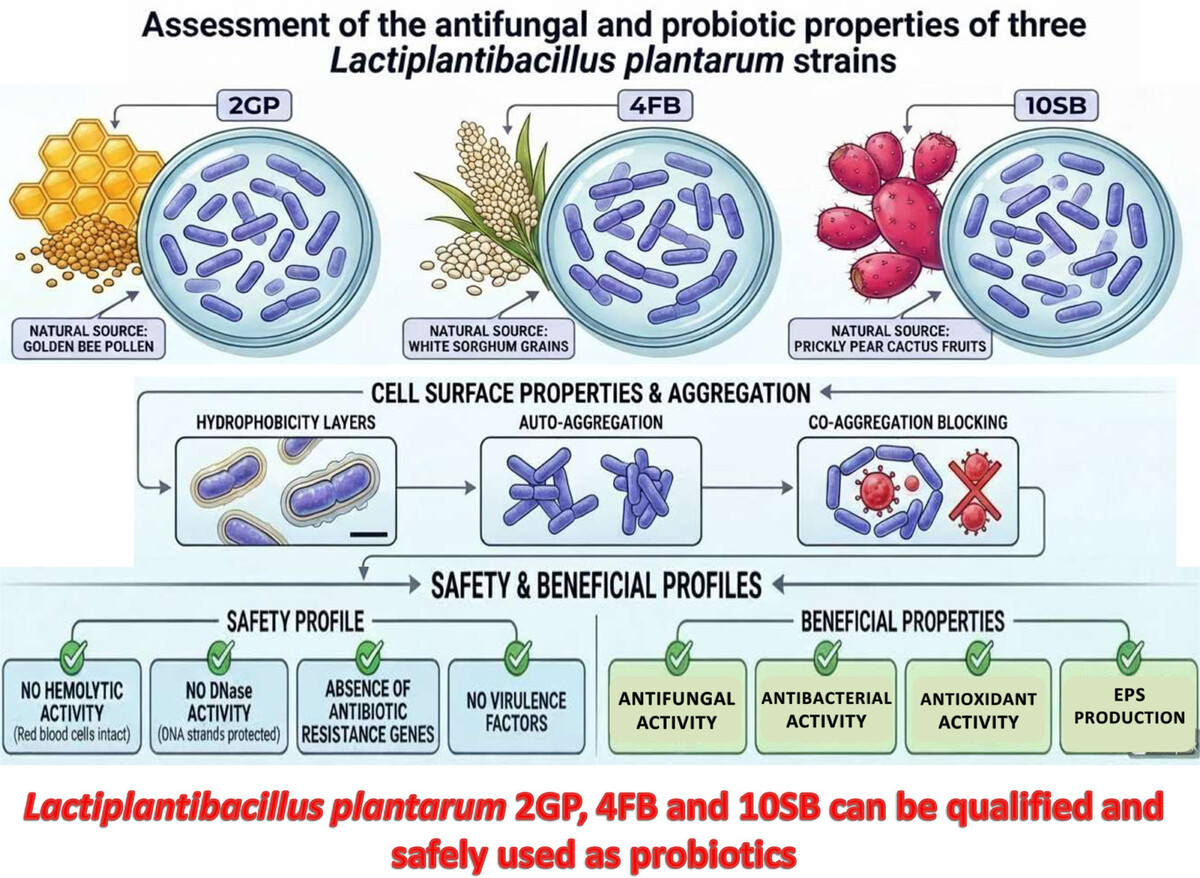

In the present study, we report three bacterial strains isolated from bee pollen, Opuntia ficus-indica fruits, and white sorghum, respectively. These strains are identified as Lactiplantibacillus plantarum (Lp. plantarum) and possess strong antifungal activity (Chbihi Kaddouri et al. 2025).

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Microbial strains

This work evaluated the antifungal and antibacterial activities of four LAB strains from different biotopes against several fungi and pathogenic bacteria. The microbial strains utilized in this study are grouped in Table 1.

Table 1

Microbial strains and their origin.

2.2. Growth conditions and antifungal activity

A 24-hour colony of each of the four LAB strains, three of them designated as Lp. plantarum 2GP, 4FB, and 10SB in addition to the fourth designated LAB 7V was added separately into the MRS broth and incubated at 30°C for 48–72 hours without shaking. The final cultures were centrifuged for 15 minutes at 6000 g before being passed through a 0.22 μM Millipore filter. After being freeze-dried, the cell-free supernatant (CFS) was added to sterile distilled water to create solutions concentrated from 5 to 25 times relative to the initial volume. The CFS solutions were stored at 4°C until they were used. (Arrioja-Bretón et al. 2020).

On Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA, Biokar) plates, mold strains were added, and they were then incubated for 7 days at 30°C (until sporulation). Fungal spores obtained were harvested by scraping the culture surface in sterile distilled water. Yeasts were inoculated in malt extract broth (2%, Biokar) and incubated at 30°C for 24 hours. A hemocytometer (Preciss Europe, Navarre, Spain) was used to determine the concentration of mold spores and yeast cells, which were then corrected to 106 spores or cells per milliliter of sterile distilled water. We used the agar well diffusion procedure in accordance with Magnusson and Schnürer (2001) methodology to evaluate the antifungal activity of CFS. Therefore, 1 mL of the fungal spore or yeast cell suspension (106 cells or spores/mL) was added to each Petri dish containing PDA. After drying, 6 mm diameter wells created in the agar using a sterile cork-borer were filled with 100 μL of LAB-CFS. After being incubated at 30°C for 24 hours, the diameter (mm) of the inhibitory zones encircling the wells was measured. MRS indicates the control without activity. Each manipulation was done in triplicate.

2.3. In vitro characterization of probiotic properties

2.3.1. Oro-gastro-intestinal transit tolerance

Based on slightly modified approaches of Damodharan et al. (2015), the response of LAB strains to simulated conditions of oral, gastric, and intestinal transit was evaluated. The experiments were conducted using a one-night culture of the LAB strain in fresh MRS broth. The agar dilution method was used to count LAB just before the simulated oro-gastro-intestinal transit experiments. Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was used to rinse twice the pellet resulting from centrifugation of 10 mL of the bacterial culture at 6000 g for 15 minutes. The three LAB strains were subjected to simulated oral conditions in 10 mL of a sterilized electrolyte mixture (sodium bicarbonate, 1.2 g; potassium chloride, 2.2 g; sodium chloride, 6.2 g; calcium chloride, 0.22 g) supplemented with 150 mg/L lysozyme; the mixture incubation is carried out at 37°C for 10 minutes.

Following a 15-minute centrifugation at 6000 g, the cells were exposed to gastric stress for 30 minutes at 37°C in 10 mL of electrolyte buffer containing 3 g/l pepsin and adjusted to a pH of 2.5. The LAB cells were separated from the gastric stress mixture using centrifugation (6000 g for 15 minutes) and then placed under intestinal stress for 2 hours in 10 mL of an electrolyte buffer (calcium chloride, 0.25 g; potassium chloride, 0.6 g; sodium chloride, 5 g; pH7), which included 3 g/l ox-bile and 1 g/l pancreatin. After every test, the viability of bacterial cells was determined by counting on dilution plates of MRS agar.

2.3.2. Cell surface properties

Hydrophobicity

The hydrophobicity test consists of measuring cell adhesion to hydrocarbons; this characteristic was established in accordance with the protocol of Collado et al. (2007), which was slightly modified. LAB strains were added in MRS broth and incubated at 37°C for 18 hours. The bacterial cultures obtained were centrifuged at 6000 g for 15 minutes; 10 mL of culture was washed twice in PBS buffer and then immersed in 10 mL of PBS. Initial optical density (OD) measurements of the mixture were taken at 600 nm (A0). Next, the cell suspension was mixed separately with equal quantities (4 mL) of cyclohexane, xylene, chloroform, and toluene, and vortexed for 2 minutes. The resulting combination was incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes to facilitate the separation of the organic and water phases. The OD600 nm of the collected aqueous phase was calculated according Equation 1:

(1)

A0 is the OD600 measured before mixing with solvents, while A is the OD600 measured after mixing with solvents.

Auto-aggregation tests

According to Zawistowska-Rojek et al. (2022), probiotic bacteria, which possess the capacity to auto-aggregate, can attach spontaneously to cells in the intestinal epithelium. The auto-aggregation capacities of the three LAB were evaluated according to the procedure described by Collado et al. (2007), which was slightly modified. Briefly, bacterial cells that had been cultured overnight were centrifuged at 6000 g for 15 minutes, washed twice with PBS, and resuspended in the same solution. Then, the suspensions’ ODs were measured at 600 nm (A0). After vortexing 4 mL of each solution for 10 seconds, the suspensions were incubated at 37°C for 24 hours, and the OD (A24h) was measured.

The auto-aggregation percentage was determined according to Equation 2:

(2)

Co-aggregation tests

The co-aggregation tests were carried out by the procedure described by Collado et al. (2007). The bacterial strains used are pathogenic, namely, Acinetobacter baumanii A144, Pseudomonas aeruginosa Pu 234, and Escherichia coli 311. The bacterial suspensions were prepared following the previously described instructions for auto-aggregation. The LAB and pathogenic strains were mixed in equal volume of 4 mL, vortexed for 10 seconds, and then incubated for 12 hours at 37°C without shaking. The suspension of each bacterial strain was considered as the control.

The co-aggregation % was calculated using the following formula (Equation 3):

(3)

Where ALab and APath are the OD600 in LAB and pathogen strain tubes, respectively, and AMix represents the OD600 of the mixture.

2.3.3. Antibacterial activity of isolated LAB strains

The antibacterial effect of the three LAB strains was tested against three pathogenic bacteria; the agar well diffusion technique under the protocol of Abouloifa et al. (2020) was used.

The four LAB strains with a concentration of 109 CFU/mL were inoculated separately in the MRS broth (1%, v/v) and incubated for 48 hours at 37°C. The bacterial cultures obtained were centrifuged at 6000 g for 15 minutes, and lyophilization was used to prepare a 20-fold concentrated supernatant. Their antibacterial properties were determined against the three pathogenic bacteria, namely, Acinetobacter baumanii A144, Escherichia coli 311, and Salmonella typhimurium.

Mueller–Hinton agar plates were initially submerged by 500 μL of the chosen pathogenic bacteria (108 CFU/mL). Following that, wells with a diameter of 6 mm were created in the agar and filled with 80μL of each concentrated supernatant. After 48 hours of incubation at 37°C, the clear zones surrounding the wells were measured. The sterile MRS broth served as a control. Each experiment was carried out three times, and the data were presented as mean ± Standard deviation.

2.4. Isolate safety evaluation

2.4.1. Antibiotic LAB resistance

The antibiotic resistance/sensitivity tests of the three LAB were evaluated by using the disk diffusion method. After being added to the MRS broth, each bacterium was cultured for 24 hours at 37°C. A volume of 100 µl of each culture adjusted to the 0.5 McFarland visual turbidity standards was spread on the MRS agar; 10 commercial antibiotic discs including: Ampicillin (AMP; 10µg), Streptomycin (S; 25µg), Imipenem (IPM;10 µg), Gentamicin (CN; 10µg), Erythromycin (E; 15µg ), Kanamycin (K; 30µg), Cephalothin (KF; 30µg), Tetracycline (TE; 30µg), Trimethoprim/Sulfamethoxazole (SXT; 25µg ), and Ampicillin/Sulbactam (SAM; 20µg) were placed on the prepared plates. After 48 hours of incubation at 37°C, the diameter of the inhibition halos is measured, and the criteria provided by the antibiogram committee of the French Society for Microbiology (CA-SFM, 2020) were adopted to interpret the results. Each disk diffusion method was performed in triplicate.

2.4.2. Hemolysis test

The red blood cell lysis test was carried out on sheep blood agar according to the protocol described by Arellano et al. (2020). On the chosen medium, fresh samples of the three LAB—2GP, 4FB, and 10SB— were placed in 2 cm lines and kept for 48 hours at 37°C. The emergence of halos surrounding bacterial lines was tracked on the plates. Following incubation, the bacterial lines can show a clear zone (complete hemoglobin destruction) (β-hemolysis), a green area (partial hemoglobin degradation of red blood cells) (α-hemolysis), or no zone (lack of hemolytic activity) (γ-hemolysis). A duplicate of each experiment was conducted.

2.4.3. DNase detection

DNase agar medium was used to assess the LAB strains’ ability to produce DNase enzyme according to the method of Varada et al. (2023). First, LAB strains were added to the MRS broth and incubated for 48 hours at 37°C. Then, 100 µL of each LAB culture was introduced into DNase agar in the form of a 2 cm long streak and kept at 37°C for 24 hours. The synthesis of the DNase enzyme is revealed by the addition of 1N HCL on the surface of the agar. A positive DNase activity is shown by the appearance of a clear zone surrounding the inoculation streak.

2.5. Qualitative assessment of Exopolysaccharides production

The production of exopolysaccharides by the three LAB was tested using the approach detailed by Kumari et al. (2020). Thus, the bacteria were streaked on modified MRS agar (sucrose at 100 g/L replaced glucose), and then incubated at 37°C for 24 hours. The production of slime was checked on grown colonies by lifting them up with a sterilized toothpick. If visible slime measuring more than 1.5 mm in length appeared, the tested bacteria were classified as positive slimy producers.

2.6. Antioxidant activity

The 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) free radical scavenging activity was measured according to the method explained by Rezqiyana and Rijai (2024) to evaluate the antioxidant activity of the three LAB strains. A 109 CFU/mL LAB strain suspension was added to a 0.05 mM ethanolic DPPH solution (1:2, v/v). It was strongly mixed and then incubated for 30 minutes at 25°C in the dark. Ethanol added to LAB cells served as the blanks, while the DPPH solution with deionized water served as the control. The mixtures were centrifuged at 6000 g for 15 minutes, and their optical densities were measured at 517 nm. To calculate the antioxidant activity, Equation 4 was used:

(4)

3. RESULTS

3.1. Activity and antifungal spectrum

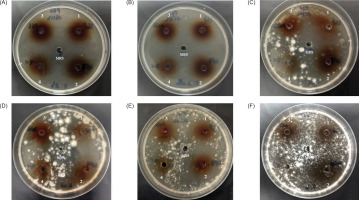

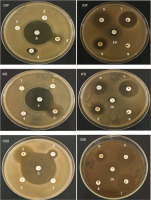

The three LAB used in the present work, namely, the strains designated 2GP, 10SB and 4FB showed a strong activity and a large antifungal spectrum; In fact, they were active against C. albicans and nonalbicans as well as the four fungi tested; these three bacteria were isolated, respectively, from three different biotopes, namely, bee pollen, white sorghum, and fruits of Opuntia ficus-indica (prickly pear). They were identified as Lp. plantarum according to the partial analysis of their 16S rDNA gene. However, strain 7V, which is also a lactic acid bacterium, showed no activity against these fungi (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Antifungal activity of CFS from Lp. plantarum 2GP (1), 4FB (2), 10SB (3), and LAB 7V (4) against Candida albicans (a); Candida nonalbicans (b); Aspergillus fumigatus (c); Aspergillus niger (d); Fusarium oxysporum (e) and Penicilium brasilianum (f); MRS indicates the control without activity.

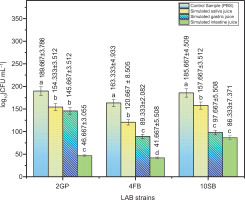

3.2. Test for oral and gastrointestinal transit

In vitro tests were conducted to determine the three LAB strains’ capacity to resist simulated conditions in the oro-gastrointestinal tract. The number of viable bacteria after exposure to the mentioned conditions is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3

Viable counts of LAB strains according to each phase of simulated oro-gastro-intestinal transit. Tukey’s multiple comparison test and the two-way ANOVA indicate that values are considerably distinct (p <0.05).

The three LAB strains showed good tolerance to the digestive stress conditions; the number of viable cells decreased only slightly after oral stress exposure, indicating oral stress tolerance. The number of viable cells continued to decline (Figure 3).

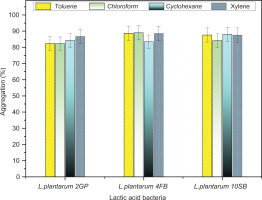

3.3. Cell surface properties

3.3.1. Hydrophobicity

The three LAB strains tested showed hydrophobicity percentages higher than 82% after their tests with the four organic solvents. It’s noteworthy that Lp. plantarum 4FB showed the highest hydrophobicity values in chloroform (89.05% ± 0.11), toluene (88.71% ± 0.14), and xylene (88.60% ± 0.25) compared to the other strains. However, in cyclohexane, it’s the strain Lp. plantarum 10SB that presents the highest percentage (87.99% ± 0.12). The details of the results obtained are reported in Figure 4.

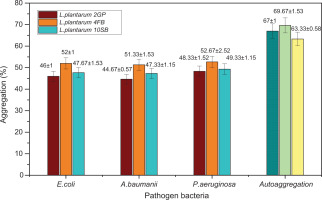

3.3.2. Auto and co-aggregation

The tests carried out showed that the three strains of LAB have both properties: auto-aggregation and co-aggregation. Auto-aggregation capacity was observed in all strains with percentages higher than 63%. In comparison to the Lp. plantarum 10SB strain (63.3%±0.57), the two strains, Lp. plantarum 2GP and Lp. plantarum 4FB, displayed comparatively higher auto-aggregation percentages with (67%±1.00) and (69.67%±1.52), respectively. In addition, each LAB strain exhibited the capacity to co-aggregate with one or the other of the three tested pathogenic bacterial strains. Figure 5 presents the results obtained from assessing the co-aggregation and auto-aggregation characteristics of presumed probiotic LAB strains.

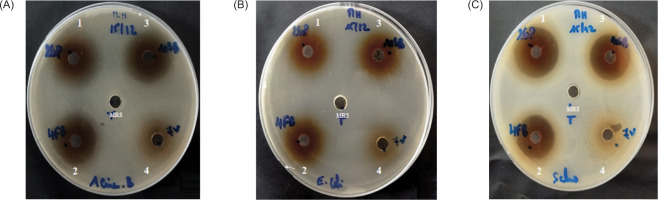

3.4. Antibacterial activity of LAB strains

Results of the agar well method showed that all the LAB strains used in this research possess significant power to limit the proliferation of harmful microorganisms, with differences in the degree of inhibition. Figure 6 shows an antagonistic impact on bacterial strains Acinetobacter baumanii A144, Escherichia coli 311, and Salmonella typhimurium. Table 2 reports the inhibition zone diameters of the three LAB strains versus the three pathogenic bacterial strains; the diameters obtained varied between 20.73 ± 0.3mm and 25 ± 0.1 mm.

Figure 6

Antagonistic activity of LAB strains against Acinetobacter baumannii A144 (a), Escherichia coli 311 (b), and Salmonella typhimurium (c). Numbers for the LAB strain supernatants; 1: Lp. plantarum 2GP, 2: Lp. plantarum 4FB; 3: Lp. plantarum 10SB; and 4: nonactive LAB 7V. In the middle of the petri dish, the MRS broth was used as a control.

Table 2

Inhibition zone diameters of LAB strains against three pathogenic bacteria using the agar-well diffusion method.

3.5. Isolate safety evaluation

3.5.1. Antibiotic LAB resistance

The resistance pattern obtained showed that the three LAB strains are resistant to Gentamicin (CN), Kanamycin (K), and Cephalothin (KF) but sensitive to antibiotics Imipenem (IPM), Ampicillin (AMP), Thrimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (SXT), Streptomycin (S), Tetracycline (TE), Erythromycin (E), and Ampicillin/sulbactam (SAM). Figure 7 illustrates the antibiotic resistance profiles obtained by using the disc diffusion method. Table 3 shows the inhibition zone diameter, in millimeter, obtained for each LAB strain.

Figure 7

Antibiotic resistance profile of the three LAB strains, 2GP, 4FB, and 10SB. 1. Kanamycin (K30). 2. Gentamicin (CN10). 3. Thrimethoprim /sulfamethoxazole (SXT 25). 4. Streptomycin (S25). 5. Imipenem (IPM10). 6. Ampicillin (AMP10). 7. Erythromycin (E15). 8. Cephalothin (KF30). 9. Tetracycline (TE30). 10. Ampicillin/sulbactam (SAM20).

Table 3

Profiles of antibiotic resistance in LAB strains identified using the disc diffusion technique.

3.5.2. DNase, hemolytic capacities, and exopolysaccharides production

The results of the hemolytic and DNase assays indicate that the three LAB strains are devoid of hemolytic activity as well as of DNase; however, they can synthesize EPS. Table 4 shows the hemolytic, DNase, and EPS production profile of the LAB strains.

3.5.3. Antioxidant activity

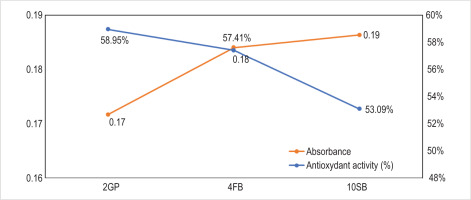

The DPPH assay was used to determine the three LAB strains’ antioxidant properties. The results are shown in Figure 8.

The results obtained show that the three LAB strains can scavenge free radicals by more than 50%. These results highlight a significant variation in antioxidant activity (%) among the three studied strains, namely, 2GP, 4FB, and 10SB. The 2GP strain exhibits the highest antioxidant activity at 59.95%, followed by 4FB (57.41%) and finally 10SB (53.09%).

4. DISCUSSION

The process of choosing new probiotic strains is complicated and involves evaluating a range of characteristics. The present study used the most significant tests conducted in vitro to assess the probiotic capacity of three LAB strains: Lp. plantarum 2GP, 4FB, and 10SB. The ability of probiotics to endure the stressful conditions of digestive transit determines whether they can survive the defenses of the host’s digestive system, as the survival rate during passage is the key element showing that probiotics could improve host health (Gao et al. 2021). The three LAB strains were examined under conditions similar to the stressful circumstances that accompany transit through the digestive tract. According to the in vitro oral stress tolerance results, the three LAB strains showed equal viability counts to the control; Chen et al. (2023) validated these results, showing that LAB retained high viability when exposed to simulated saliva conditions. This might be explained by the role of oral stress in upregulating the hsp gene expression in LABs. Locally existing lysozyme in the mouth cleaves the peptidoglycan that constitutes bacterial cell walls, acting as an antibacterial agent (Schulz 2023). Because of that, one of the essential characteristics of probiotic strains is their resistance to lysozyme activity. In addition to their ability to tolerate oral stress, probiotic potential LAB strains must be able to survive the low pH stress of stomach juice and an abundance of pepsin. With a pH of nearly 2.5 to 3.5 and a bile concentration around 0.3%, gastric juice eliminates the majority of bacteria that enter the human digestive system (Akritidou et al. 2022). Since stomach digestion can typically take up to 3 hours, the criteria that must be considered when choosing probiotic bacteria are tolerance to acidic pH and bile. As a result of our in vitro tests, the three LAB strains presented the capacity to survive in generated stomach juice with a large number of viable cells in terms of gastric stress resistance. Similar to this, Echegaray et al. (2023) have previously documented that strains of Lp. plantarum are tolerant of gastric conditions. This could suggest that the gastric environment’s conditions improve the pH balance in and out of the cell by regulating proton transfer through the actions of urease, glutamic acid decarboxylase, arginine deaminase, and membrane ATPase. The small intestine is an additional challenge that probiotic strains need to surmount; pancreatic juice and salts in the bile are examples of intestinal stress (Bustos et al. 2024). The three LAB strains in this investigation demonstrated tolerance to the environment of the simulated small intestinal tract. For this purpose, Liu et al. (2024) demonstrated Lp. plantarum strains’ resistance to intestinal stressful conditions. This tolerance may be the consequence of LAB strains producing biliary salt hydrolases (BSH). Bile salt is an essential component of fat digestion because it acts as a physiological detergent that emulsifies and dissolves fats. Strong antibacterial activity is also provided by bile’s capacity to operate as a detergent, principally through the breakdown of bacterial membranes (Adugna and Andualem 2023); our LAB strains must be able to resist the harmful effects of bile and the activity of digestive enzymes to be consumed as probiotic species. Following exposure to difficult oro-gastrointestinal circumstances, the three LAB strains showed the capacity to survive in large enough numbers. Consequently, these strains satisfied one of the most crucial criteria for selecting probiotics. It has been shown that the surface proteins of probiotic bacterial strains affect both competitive adhesion and cell defense against pathogens, and the higher hydrophobicity can be because of the presence of glyco-proteinaceous compounds at the bacterial cell surface; conversely, hydrophilic surfaces affect probiotics’ capacity to attach and are associated with polysaccharide content. Furthermore, probable probiotic candidates were assessed for their capacity to bind to intestinal epithelial cells, which necessitated the cell surface to have hydrophobic properties and its ability to auto- and co-aggregate (Wang et al. 2024); thus, the three LAB strains showed an elevated level (>80%) of hydrophobicity through hydrocarbons. However, significant variations were noted between the three strains. This could be attributed, among other things, to variations in the strains’ cell wall structure. In this regard, (Choi et al. 2015) reported that the percentage of hydrophobicity varies not only depending on the bacterial species but also on the strains, the bacteria’s age, and the structure of the cell surface. In this regard, the work of Dell’Anno et al. (2021) reported that Lp. plantarum presents a greater hydrophobicity compared to L. reuteri which could affect their different colonization capacities. Furthermore, contrary to previous studies, the three LAB strains showed a higher level of hydrophobicity. Because of this surface hydrophobicity, strains and human epithelium cells could interact more effectively, which will result in greater bacterial–epithelial cell interaction and longer retention of the probiotic in the intestines.

In terms of aggregation, the three LAB isolates exhibited elevated levels of auto-aggregation (>60%) and co-aggregation (>40%); however, the highest values were recorded for strain Lp. plantarum 4FB. These results are in accordance with the findings of previous studies by Isenring et al. (2021), demonstrating Lp. plantarum strains’ capacity for auto- and co-aggregation. It was demonstrated that the co-aggregation percentages varied according to the pathogen strain and how it interacted with the LAB strains under examination; in addition, it has been reported that aggregation properties vary among bacterial strains (Das et al. 2016). The ability to develop an elevated cell density in the intestines and to attach to the intestinal mucous membrane and epithelial cells is largely determined by auto-aggregation (Zawistowska-Rojek et al. 2022). However, co-aggregation is associated with the capacity to create a barrier that prevents germs’ colonization in the intestines. It is essential to select probiotic strains that prevent the proliferation of pathogenic bacteria in the gastrointestinal tract. The three LAB strains showed inhibitory activity against the pathogenic bacteria Escherichia coli 311, Salmonella typhimurium, and Acinetobacter baumanii A144. This result is in agreement with those of previous studies demonstrating the antibacterial effect of Lp. plantarum strains against pathogenic bacteria. Organic acids, reuterin, hydrogen peroxide, and low-molecular mass peptides are a few examples of antimicrobial compounds that are responsible for LAB’s antibacterial activity. When utilized as probiotics, the antibacterial qualities exhibited by the three Lp. plantarum strains would be crucial in treating intestinal infections. The three LAB strains 2GP, 4FB, and 10SB were assessed for their antifungal activity toward various molds implicated in human mycoses besides their antibacterial activity, and they showed high activity against all tested fungi. Results from several studies have also confirmed that Lp. plantarum possesses strong activity and broad antifungal spectrum. The safe use of probiotics for ingestion by humans is another important characteristic that needs to be examined (Da Silva et al. 2024). In this context, there was no hemolytic or DNase activity showed by any of the three Lp. plantarum strains; this represents two properties that any bacteria qualified as probiotic must possess. In other words, the failure to produce hemolysins and DNase, two virulence factors, suggest that the three LAB strains may be safe for consumption. In addition, a strain qualified as probiotic must not possess transmissible antibiotic resistance genes, in order to avoid their transfer to the intestinal microbiota. The three strains in the present study were sensitive to antibiotics such as streptomycin, ampicillin, tetracycline, erythromycin, imipenem, ampicillin/sulbactam, and thimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole; nevertheless, they exhibited resistance to cephalothin and both aminoglycoside antibiotics (gentamicin and kanamycin). According to Abriouel et al. (2015), most strains of Lactobacillus have an innate resistance to aminoglycosides, such as streptomycin, gentamicin, and kanamycin, but our three Lp. plantarum strains are sensible to streptomycin. Probiotic resistance to antibiotics is recognized as a safety problem when genes of resistance are present on mobile genetic elements and may therefore be transferred to pathogenic bacteria. Paradoxically, intrinsic resistance is an advantage because it can assist probiotic bacteria to survive in the digestive system while receiving medical therapy with antibiotics. In addition, our potential probiotic isolates demonstrated the capacity to generate exopolysaccharides; these polymers have biological properties that include immunomodulation, antioxidant, antitumor, antiviral, anticoagulant, and cholesterol-lowering effects (Jiang & Yang 2018; Zhang et al. 2024). At last, the antioxidant properties of the three LABs strains were examined, and based on the results, their activity ranged from 53.09% to 59.95%. These results were consistent with prior research on the antioxidant capacities of strains of Lp. plantarum (Xu et al. 2023). Probiotics strains possessing antioxidant properties can protect against diseases caused by oxidative stress, and also defend the intestinal microbial ecosystem against free radicals (Echegaray et al. 2023; Vougiouklaki et al. 2023; Zare et al. 2024).

The results obtained highlight the remarkable potential of certain Lp. plantarum strains as both antifungal agents and probiotics. Their ability to inhibit a broad spectrum of pathogenic fungi, combined with good tolerance to conditions simulating oro-gastro-intestinal transit, high hydrophobicity, and notable aggregation properties, is a major asset with regard to their application in functional food or biocontrol. However, in spite of these promising results, certain limitations remain, notably the absence of in vivo trials and the lack of precise identification of the antifungal metabolites responsible for the effects observed. These factors need to be studied in greater depth to better characterize the mechanisms of action and validate efficacy under real conditions of use.

To validate the efficacy of Lp. plantarum strains under real-life conditions, use murine or avian models depending on the target application (food, feed, etc.) to assess tolerance, intestinal colonization, and the antifungal effect in vivo; analyze the impact of strains on the intestinal microbiota to observe microbial interactions and probiotic persistence; and monitor cytotoxicity, intestinal translocation, and immune responses. To elucidate the mechanisms of action, techniques such as LC-MS-MS, RMN, or GC-MS should be used to identify and quantify the metabolites produced by the strains, inactivate certain genes to confirm their role in the biosynthesis of antifungal metabolites, and isolate compounds of interest and test their independent antifungal activity on cultures of pathogenic fungi. To validate use in commercial formulations, it makes sense to incorporate the strains into dairy, vegetable, or cereal products to test their viability and antifungal efficacy; assess the stability of antifungal effects under different conditions of temperature, humidity, and duration; and explore microencapsulation or freeze-drying to preserve the viability and activity of the strains. To enhance efficacy, it is convenient to combine Lp. plantarum with other probiotic strains or beneficial bacteria to increase antifungal activity, and to ensure that there is no antagonism between strains in multibacterial formulations.

5. CONCLUSION

The findings of this study have shown that the three strains of LAB defined as Lp. plantarum 2GP, 4FB, and 10SB have, in addition to antifungal activity, properties that can qualify them as probiotics. Indeed, they have shown the ability to inhibit molds and yeasts that can compromise human health; in addition, they have properties that allow them to survive in the stressful conditions of oro-gastrointestinal transit, and other properties such as co-aggregation with pathogenic bacteria, auto-aggregation ability, hydrophobic qualities, antagonistic action toward pathogens, synthesis of exopolysaccharides, and antioxidant activity. According to these results, these three Lp. plantarum strains can be qualified and possibly used as probiotics. Nevertheless, further research is needed to confirm their safety and efficacy in vivo, as well as to explore the metabolic pathways involved in their biofunctional activities. Larger-scale studies incorporating animal or clinical models, as well as an omics approach, represent interesting prospects for advancing the exploitation of these strains in commercial formulations.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors would like to acknowledge all individuals and institutions who contributed to the successful completion of this work. Their support, guidance, and valuable discussions are gratefully appreciated.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

C.K.A did research concept and design, collection and/or assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation, writing the article, and final approval of the article. E.S was responsible for research concept and design, writing the article, and critical revision of the article. M.Y looked into data analysis and interpretation, writing the article, critical revision of the article, and final approval of the article. B.M was involved in data analysis and interpretation, writing the article, and critical revision of the article. M.Z did collection and/or assembly of data, and data analysis and interpretation. E.M was responsible for collection and/or assembly of data, critical revision of the article. E.A did collection and/or assembly of data, and data analysis and interpretation. B.A was responsible for supervision, research concept and design, data analysis and interpretation, writing the article, critical revision of the article, and final approval of the article.