1. INTRODUCTION

Minthostachys mollis (Benth.) Griseb, popularly known as muña, is a plant native to the Peruvian and Bolivian Andes and used ethnomedicinally to treat various health problems, mainly for gastrointestinal system disorders, such as stomach pain, colic, flatulence, diarrhea, as well as other symptoms such as nausea, headache, respiratory tract diseases, rheumatism, impotence, and menstruation induction, among others (Schmidt-Lebuhn, 2008). The various ways of using the muña include infusions, decoctions, fleets, aromatherapy, “Walt’aska” plasters, and macerates and can also be used as a single component or mixed with other plants (Otoya, 2020).

Regarding its botanical description, a study carried out by Lupaca et al. (2009) have demonstrated differences between wild and cultivated species, so their main morphoanatomical characteristics, respectively, will be listed as follows: erect growth habit (53.84% in wild) and semierect (51.55%), pubescence distributed mainly in the nerves (69.23% and 43.30%), leaves in acute form (84.61% and 63.91%), pale and purple (wild) or green and purple predominance color in stem (cultivated), the size of the floral peduncle fluctuated between large, medium, and small, in equal percentages for wild type (30.76%), whereas the medium size was predominant in cultivated type (38.14%). The sub number nude tops were 3 on each side of the nude (61.53% and 57.53%); the predominant color of the flower varied between white and white with violet spots on the large petal, in equal percentages for wild type (46.15%), whereas the white color was predominant in cultivated type (50.52%), and all the options studied presented seeds (Lupaca et al., 2009).

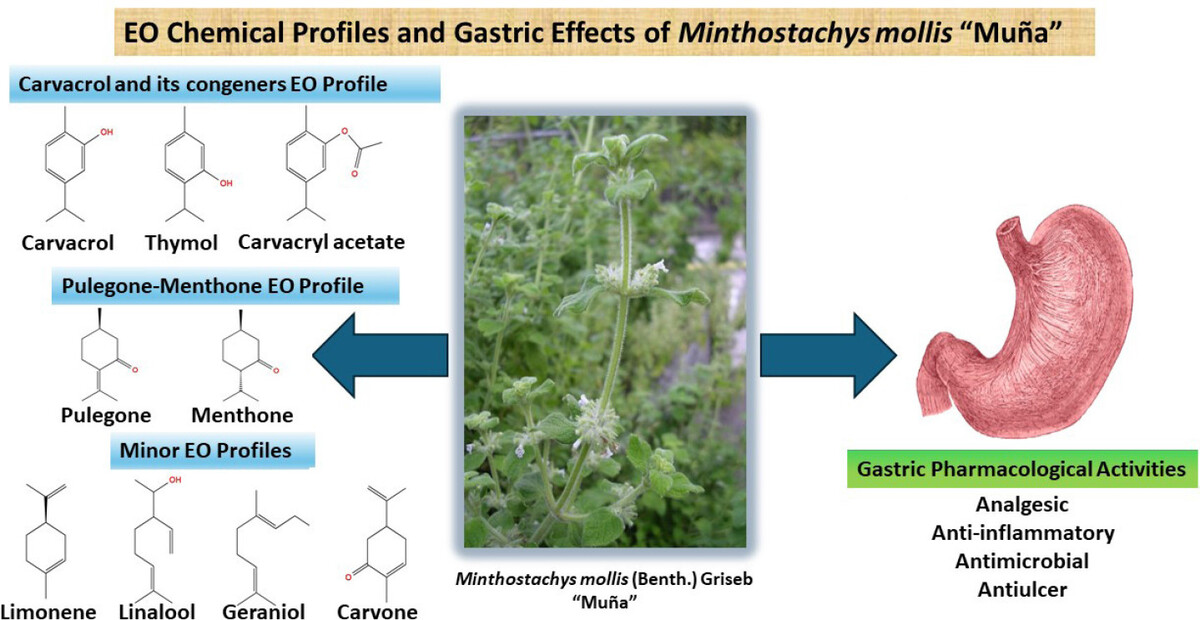

The main pharmacological activities of muña have been related to its EO, which has demonstrated potent antibacterial and antifungal activity against different microbial species that affect the respiratory, digestive, and urinary tracts (Cayo-Rojas et al., 2021; Sánchez-Tito et al., 2021). Furthermore, the effects of M. mollis on the gastric tract have also been continuously investigated, so that an updated and comprehensive review of the studies published to date is necessary while also considering the aspects arising from the chemical differences of its EOs. Therefore, the objective of this review is to provide an integrated and critical view of the EO chemistry and gastric pharmacology of M. mollis.

2. CHEMICAL CONSIDERATIONS OF MUÑA ESSENTIAL OIL

The main information on the M. mollis EOs chemistry is found in Table 1, which classifies the substances with values equal to or greater than 5% of their compositions as major components. The various studies on the chemical composition of M. mollis EO reveal two main types: those rich in pulegone and menthone (PMEO) and those rich in carvacrol and/or its congeners (CCEO). PMEO are found in all samples collected in Peruvian territory, except for one, from Tarata, which presents only menthone among the major components. In addition, the PMEO type is found in other countries such as Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, and Argentina.

Table 1

Summary of the main volatile compounds isolated from different M. mollis collections.

| Main compounds | Parts used | Extraction methoda | Location and date of collection | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carvacrol (21.04%), thymol (13.11%), germacrene D (11.85%), eudesmol acetate (11.32%), isolongifoliol acetate (10.94%), eucalyptol (10.04%), and pulegone (9.84%) | Leaves | HD | Pamplona, Colombia | (Torrenegra-Alarcón et al., 2016) |

| Eudesmol acetate (21.32%), isolongifoliol acetate (20.94%), germacrene D (11.85%), eucaliptol (10.04%), and pulegone (9.84%) | Leaves | SD | Pamplona, Colombia; June 2009, afternoon | (Conde et al., 2012) |

| Menthone (32.9%), eucalyptol (28.1%), trans-menthone (11.9%), O-cymene (9.6%), and octen-1-ol acetate (5.8%) | Fresh leaves and branches | SD | Tarata, Peru | (Sánchez-Tito and Collantes-Díaz, 2021) |

| Carvacryl acetate (44.01%), carvacrol (16.51%), menthone (8.20%), and piperitone (5.40%) | Leaves | SD | Cotopaxi, Ecuador | (Rojas-Molina et al., 2024) |

| Thymol (73.76%), carvacrol (10.94%), and p-Cymene (7.28%); | Leaves | MWHD | Pamplona, Colombia | (Torrenegra-Alarcón et al., 2015) |

| eudesmol acetate (22.44%), isolongifoliol acetate (21.75%), germacrene D (12.75%), and eucalyptol (11.04%) | Leaves | HD | Pamplona, Colombia | |

| Pulegone (8.82%) and menthone (5.92%) | Fresh leaves | SD | Moya District, Huancavelica, Peru; Feb 2014, early morning | (Pena amd Gutiérrez, 2017) |

| Pulegone (30.17%), menthone (16.55%), menthol (15.23%), p-Menthanone (10.49%), and B-caryophyllene (5.0%) | Leaves | SD | Huancavelica, Peru | (Paucar-Rodríguez et al., 2021) |

| Pulegone (36.68%) and menthone (24.24%) | Aerial parts | SD | Tarma, Peru; Sep-Oct 2005 | (Cano et al., 2008) |

| 1-tetradecene (23.14%), 2S-Transmenthone (23.00%), and pulegone (13.21%) | Aerial parts | SD | Tarma, Peru | (Ruitón and Chipana, 2001) |

| 2S-trans-Menthone (41.48%), pulegone (16.02%), y-Terpinene (7.55%) | Aerial parts | SD | Huaraz, Peru | |

| 2S-trans-Menthone (34.51%), pulegone (28.62%), and nerolidol (5.08%) | Aerial parts | SD | Pampas, Peru | |

| Petroleum ether fraction: cis-Menthone (39.8%), eucalyptol (30.2%), trans-Menthone (9.4%), o-Cymene (7.9%), Octen-1-ol acetate | Fresh leaves and branches | ES | Tarata, Peru; Sep 2019 | (Sánchez-Tito and Collantes-Díaz, 2021) |

| Petroleum ether fraction: cis-Menthone (39.8%), eucalyptol (30.2%), trans-Menthone (9.4%), o-Cymene (7.9%), Octen-1-ol acetate (7.7%); Dichloromethane fraction: Thymol (31.2%), Pulegone (25.1%), cis-p-Menthane-3-one (19.8%), Isomenthone (12.6%); Methanol fraction: a-Terpineol (43.6%), Linalool (32.9%), Borneol (13.1%), and (-)-Spathulenol (9.1%) | Fresh leaves and branches | ES | Tarata, Peru; Sep 2019 | (Sánchez-Tito and Collantes-Díaz, 2021) |

| Trans-Menthone (58.86%) and pulegone (15%) | Leaves and branches | SD | Huancayo, Peru | (Díaz-Ledesma, 2005) |

| Pulegone (55.2%) and trans-menthone (31.5%) | Fresh leaves | HD | Tuname, Venezuela; Jan 2008 | (Mora et al., 2009) |

| Carvacryl acetate, carvacrol, pulegone, and menthone | Aerial parts | n.d. | Bogotá, Colombia | (Chica et al., 2007) |

| Pulegone (76.3%) and limonene (6.8%) | Aerial parts with flowers | HD | Padremonti, Tucumán, Argentina; Nov-Mar 2006-2007 | (Elechosa et al., 2007) |

| Carvacryl acetate (44.0-50.3%), Carvacrol (19.9-23.5%), and Terpinene (2.7-6.2%) | Aerial parts with flowers | HD | Río Nío a, Tucumán, Argentina; Nov-Mar 2006-2007 | |

| Pulegone (45.8%), menthyl acetate (12.6%), and isomenthone (10.2%) | Aerial parts with flowers | HD | Río Nío b, Tucumán, Argentina; Nov-Mar 2006-2007 | |

| Limonene (35.7%) and piperitenone (18.3%) | Aerial parts with flowers | HD | La Florida, Tucumán, Argentina; Nov-Mar 2006-2007 | |

| Carvacryl acetate (39.9%), carvacrol (19.1%), and terpinene (10.1%) | Aerial parts with flowers | HD | Chorrillos, Tucumán, Argentina; Nov-Mar 2006-2007 | |

| Pulegone (57.1%), piperitenone (10.8%), and limonene (5.4%) | Aerial parts with flowers | HD | El Cajón, Tucumán, Argentina; Nov-Mar 2006-2007 | |

| Dihydrocarvone (45.4%) and carvone (36.2%) | Aerial parts with flowers | HD | Tafi del Valle, Tucumán, Argentina; Nov-Mar 2006-2007 | |

| Linalool (68.5-71.7%) | Aerial parts with flowers | HD | Gonzalo, Tucumán, Argentina; Nov-Mar 2006-2007 | |

| Carvacryl acetate (31.4%), carvacrol (15.2%), and linalool (13.4%) | Aerial parts with flowers | HD | Siambón, Tucumán, Argentina; Nov-Mar 2006-2007 | |

| Menthone (23.8-52.6%) and pulegone (38.6-49.2%) | Aerial parts with flowers | HD | Córdoba, Argentina; Nov-Mar 2006-2007 | |

| Pulegone (52.0-76.5%) and menthone (13.2-39.1%) | Aerial parts with flowers | HD | San Luís, Argentina; Nov-Mar 2006-2007 | |

| Pulegone (28.0%), menthone (9.3%), limonene (9.0%), and piperitenone (6.6%) | Aerial parts with flowers | HD | Balcozna, Cajamarca, Argentina, Nov-Mar 2006-2007 | |

| Menthone (13.2%), pulegone (12.4%), cis-Dihydrocarvone (9.8%), Carvacryl acetate (8.8%), cis-Piperitone epoxide (7.8%), Piperitone (6.7%), p-Cymene (5.6%), and limonene (5.5%) | Fresh aerial parts | HD | San Marcos, Cajamarca, Peru; January 2017 | (Benítes et al., 2018) |

| Pulegone (40.94%) and menthone (32.72%) | Leaves | SD | Pomacochas, Peru | (Villar-Calero et al., 2021) |

| Pulegone (45.04%) and menthone (30.17%); | Fresh leaves | SD | Comas, Concepción, Peru | (Castro-Mattos, 2012) |

| Pulegone (52.32%), Menthone (24.81%) | Dry leaves | SD | Comas, Concepción, Peru | |

| D-menthone (39.75%), Pulegone (22.45%), (2S-trans)-5-methyl-2- (1-methylethyl)-(cyclohexanone) (10.24%) | Leaves | SD | Vinchos, Huamanga, Peru; Rain Season (Sep-Mar), 6-10 am | (Wisa et al., 2017) |

| Geraniol (24.93%), citronelol (14.84%), geranyl acetate (8.60%), neomenthol (7.97%), 13(16), 14-labdien-8-ol (6.76%), L-menthone (5.87%), L-linalool (5.36%), p-Menth-4-en-3-one (6.20%); | Aerial parts | HD | Pichincha, Ecuador | (Fernandes et al., 2018) |

| Neomenthol (32.34%), pulegone (28.42%), L-menthone (19.32%), and spathulenol (5.76%) | Leaves and flowers | HD | Pichincha, Ecuador | |

| 2S-trans-Menthone (41.48%), pulegone (16.02%), and y-Terpinene (7.55%) | Fresh plant | SD | Huaraz, Peru | (Aquije-Huaroto, 2015) |

| Pulegone (40.07%), menthone (17.16%), piperitenone epoxide (12.93%), and piperitenone oxide (8.55%) | Aerial parts | SD | Tambillo, Huánaco, Peru | (Lupaca et al., 2009) |

| Pulegone (41.73%), menthone (24.24%), isomenthone (6.69%), and piperitenone epoxide (5.92%) | Aerial parts | SD | Mitochuco, Huánaco, Peru | |

| Carvacryl acetate (18.95%), trans-Caryophyllene (10.05%),Germacrene D (9.46%), carvacrol (7.60%), limonene (6.69%), o-Cymene (6.46%), y-Terpinene (5.37%), bicyclogermacrene (5.33%); | Fresh leaves | SD | Carchi, Ecuador | (Moreno et al., 2019) |

| trans-Caryophyllene (13.83%), Sabinene (10.1%), Germacrene D (6.69%), 1-methyl-2-(1-methylethyl)-benzene (5.87%), a-Copaene (5.86%), (+) Spathulenol (5.51%) | Stored leaves | SD | Carchi, Ecuador |

On the other hand, CCEO-type EOs present carvacrol, thymol, and carvacryl acetate as the main representatives of carvacrol congeners. They were found in samples from Argentina, Colombia, and Ecuador but were not found with this profile in samples from Peru. Interestingly, in the Río Nío area, Tucumán, Argentina, two predominant types of EO were identified, whereas in the Bogotá sample, two major compounds of each type were described for the same oil (Chica et al., 2007; Elechosa et al., 2007).

Chemical profiles can be decisive for the scope of their pharmacological actions, as well as for their pharmacological potency, since pulegone, menthone, and other related substances such as isomenthone and even limonene have specific mechanisms of action for analgesic, anti-inflammatory, and insecticidal activities, while carvacrol and thymol and congeners, although they also present these activities, exhibit peculiar mechanisms, in addition to more pronounced antioxidant activity due to the presence of an aromatic ring in their structures (Charlet et al., 2021; Guimarães et al., 2012). In addition, other less common profiles were found for M. mollis EOs, such as those rich in limonene and piperitenone in the sample from La Florida (Argentina), linalool (Gonzalo, Tucumán, Argentina), geraniol/citronellol (Pichincha, Ecuador) and dihydrocarvone and carvone (Tafi del Valle, Tucumán) (Elechosa et al., 2007; Fernandes et al., 2018). The substances eudesmol acetate and isolongifoliol (Colombia) and germacrene D and bicyclogermacrene (Colombia and Ecuador) in CCEO-type oils are also highlighted, as well as 1-tetradecene, the majority in a PMEO-type oil, and eucalyptol (Conde et al., 2012; Moreno et al., 2019; Ruitón and Chipana, 2001; Torrenegra-Alarcón et al., 2016).

In addition to geographical factors, climate, soil type, and interaction with predatory or pollinating insects can also influence the preferential biosynthesis of substances in EOs, so further studies must be conducted to clarify these issues. Furthermore, other studies demonstrated that mechanical injuries and interaction with predators can also change the quantitative profile of M. mollis EOs, especially those of the PMEO type, as well as their yields (Banchio et al., 2005a, 2005b, 2007; van Baren et al., 2014). Finally, regarding the standardization of EO, it is also necessary to be concerned about the extraction method, since there were differences between extractions under hydrodistillation and steam distillation, or even when microwave extraction is used, in addition to the difference in composition between the extraction of fresh plant and dry plant, factors that can make a difference from a biological point of view (Castro-Mattos, 2012; Conde et al., 2012; Moreno et al., 2019; Torrenegra-Alarcón et al., 2015; Torrenegra-Alarcón et al., 2016; Benites et al., 2018).

3. GASTRIC EFFECT OF MUÑA

Gastritis is an inflammation of the gastric mucosa, the lining that protects the inside of the stomach. It can be acute, developing quickly, or chronic, with symptoms persisting over time. Its main causes include bacterial infections, such as Helicobacter pylori, excessive alcohol consumption, irritating medications like nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and severe stress. It may also be associated with autoimmune diseases, food allergies, or bile reflux. Risk factors include an unbalanced diet, smoking, and frequent consumption of irritating foods. Gastritis can cause symptoms such as abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and a feeling of fullness. Treatment depends on the cause and may involve dietary changes, medications to reduce acidity, and eradication of infections (Chen et al., 2023: Hua et al., 2023). In this sense, muña (M. mollis) is one of the most widely used phytotherapeutic resources in Andean countries for the treatment of gastritis and other stomach disorders. Some studies have been published demonstrating the effectiveness of this species in mitigating gastric disorders or acting in related mechanisms. For example, the work of Velarde-Negrete et al. (2022) evaluated the analgesic and gastroprotective activities of muña extract and its combination with llantén (Plantago major) in both extract and infusion forms. The results for the percentage of analgesic activity, in relation to the number of writhes induced by glacial acetic acid, were 57.1% for the muña extract, 72.1% for the llantén extract, 76.4% for the combined extracts, and 81.4% for the infusion. In terms of effectiveness compared to the positive control, the muña extract achieved 70.8%, the llantén extract 89.4%, the combined extracts 94.7%, and the infusion exceeded 100%.

The gastroprotective activity, based on the number of lesions induced by the ulcerogenic agent, was 50% for the muña extract, with an effectiveness of 83.33% and 40% for the llantén extract, with an effectiveness of 66.67%. The same activity and effectiveness were observed for the combined extracts. For the infusion, the gastroprotective activity was 60%, with an effectiveness of 100%. Similarly, based on the lesion size in millimeters, the gastroprotection was 62.7% for the muña extract, with an effectiveness of 86.5%, 50% for the llantén extract, with an effectiveness of 68.9%, 53.9% for the combined extracts, with an effectiveness of 74.3%, and 69.6% for the infusion, with an effectiveness of 95.9%. These values indicate that the combined infusion shows better results than the extracts, likely due to the synergistic action and the differential extraction of components during the infusion process. Furthermore, synergy is also observed in analgesic activity with the combined administration of the extracts (Velarde-Negrete et al., 2022). The gastroprotective synergistic effect provided by coadministration with other species was also observed when the muña extract was combined with the hydroethanolic extracts of Malva sylvestris, Solanum tuberosum, and Uncaria tomentosa. In the study of Castillo-Saavedra (2010), it was found that Minthostachys mollis, Malva sylvestris L., and its combination had a protective effect against the acute injury of gastric mucosa induced by ethanol in rats, evidenced by a low number and diameter of gastric ulcers. However, in these trials, the methanolic extract of M. mollis (0.4 g/kg, 2 mL) demonstrated greater efficacy than the combination and the methanolic extract of M. sylvestris in reducing hyperemia and tissue erosion (80% reduction), even surpassing the positive control, sucralfate, in the latter aspect. This concentration was also the most effective in decreasing hemorrhage (90% reduction), the number of ulcers (50% reduction), and ulcer size (75% reduction) (Castillo-Saavedra, 2010). On the other hand, the results of the study developed by Llontop et al. (2020) showed that the mix of M. mollis, S. tuberosum, and U. tomentosa extracts (0.4 mL/kg, 20%) led to a 96.2% decrease in gastric lesions induced by ethanol, while sucralfate caused a 91.5% decrease (Llontop et al., 2020). It was also noted that the administration of M. mollis infusion favourably influences digestion in people aged 30 to 60 years who consume high-fat foods, with 69.8% reporting improved digestion (Herrera-Guzman and Poma-Tello, 2019). This result was corroborated by the study of Mallqui-Villar (2015), in which it was demonstrated that the consumption level of M. mollis infusion by woman of 25–45 years once a day for the treatment of gastrointestinal disorders was 63.3%, whereas for food poisoning, treatment of indigestion and gastritis was equal to 93.3%, 76.7%, and 53.3%, respectively (Mallqui-Villar, 2015).

The effect of the EO of M. mollis on H. pylori was investigated by Carhuapoma et al. (2009), who demonstrated that the oil exhibited a minimum inhibitory concentration and minimum bactericidal concentration of 2 µg/mL, an inhibition zone of 17.07 mm, and 177.27% inhibition compared to the ciprofloxacin standard, using a concentration of 450 µg/mL of the oil (Carhuapoma et al., 2009). However, the clinical study by Rojas-Wisa (2017) indicated that the administration of the EO alone was not effective in eliminating H. pylori bacteria in patients hospitalized at the army hospital, even though the administration of the oil was carried out via gel capsules and concomitantly with proton pump inhibitors, such as omeprazole, since capsule dissolution studies are necessary and drug interactions may occur (Wisa, 2017). It is highly likely that the combination of substances present in the extract and EO of M. mollis may act synergistically in the treatment of gastric disorders reported in ethnopharmacological documents, as infusion is an extraction method capable of obtaining such substances. The extract of M. mollis contains phenolic and polyphenolic compounds with gastroprotective activity, such as rosmarinic acid, as well as the major flavonoids isosakuranetin and naringenin and/or their glucosides, which exhibit pronounced anti-inflammatory and gastroprotective activity (de Oliveira Formiga et al., 2021; Kang and Kim, 2017; Li et al., 2021; Paz-Soldán et al., 2023). In addition, pulegone, menthone, carvacrol, and thymol have analgesic, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial activity, which are also related to the characteristic symptoms of gastritis (Charlet et al., 2021; Flamini et al., 1999; Guimaraes et al., 2012; Ghori et al., 2016; Grande et al., 2021; Silva et al., 2012; Zaia et al., 2016; Zhao et al., 2023).

4. CONCLUSION

According to the literature compiled and discussed in this section, M. mollis is an effective natural resource to treat gastric problems. Its EO presents two main chemical profiles according to the geographical conditions, so that the pulegone/menthone profile is characteristic of Peruvian lands. However, more detailed research on how the chemical profiles of M. mollis interfere with pharmacological activity must be conducted, as well as the development of formulations that enhance its efficiency.