ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

This study stands unique as the wound-healing potency of mucus from Pangasianodon hypopthalmus (Teleost fish) has not been studied yet, and teleost fish have the property of fin regeneration.

GC-MS results revealed that oleic acid was present at the highest concentration in the mucus of teleost fish, thus paving an easy method to obtain oleic acid without harming the fish.

Docking studies showed favorable binding interaction between TP53 and oleic acid, suggesting a potential modulatory effect on its activity.

Integration of lyophilized fish mucus into multifunctional hydrogels would enhance ROS antibacterial activity and ROS scavenging activity.

1. INTRODUCTION

Fish has long been regarded as an accessible and important source of protein used in the Nutraceuticals and Pharmaceuticals industry, benefiting people all over the world (Paital, 2018). Fish and other marine animals make up almost half of the biological diversity and also a potential source of new bioactive substances that are being used to continuously enhance human health (Bayir et al., 2025; Chiesa et al., 2016). Bioactive compounds from fishes have the potency to be used in pharmaceuticals, since they have a unique combination of bioactive substances such as Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PFAs), Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), protein hydrolysates, omega-3 PFAs, peptides, amino acids, collagen, vitamins, gelatin, fish oil, fish bone, fat-soluble vitamins, and minerals (Gomathy et al., 2023; Mardiah et al., 2025). As an added advantage, the high amount of long-chain omega-3 (PFAs) has been linked to have primary therapeutic potential in human diet (Das et al., 2024). Several studies also suggest that different bioactive components from marine sources have been discovered to show profound effects on human health, such as wound healing (S. A. Ashraf et al., 2020; Gomathy & Pappuswamy, 2024). Omega-3 fatty acid guards against multiple diseases like heart attack and stroke. The American Heart Association recommends consuming fish at regular intervals, which equates to 1-2 servings per week from which EPA and DHA, widely obtained from fish that contain omega-3 fatty acid, a meet the cumulative weekly equivalent of recommended daily intake of roughly 200–500 mg (Innes & Calder, 2020; Papanikolaou et al., 2014, pp. 2003–2008). Also, research on the therapeutic value of fish and fish-derived commercial products reveals that they are rich in other beneficial components that offer numerous health advantages (J. Chen et al., 2022).

Many medical researchers use nutraceuticals for preventive purposes because of the substantial therapeutic benefits of fish and fish byproducts (Wang et al., 2023). Fish-based biomaterials have the potential to mitigate and address a wide range of illnesses, including but not limited to cardiovascular disorders, cancer, viral infections, rickets, dermatological issues, hypertension, parasite infections and pregnancy-related ailments (Dale et al., 2019). In addition to all the above-mentioned health benefits, fish-derived biomaterials contain anti-oxidant, anti-coagulant properties, and anti-inflammatory properties.

The interface between the human body’s internal and external environments is made up of the skin tissue (Chia & McClure, 2020). Its intricate structure, which consists of both cellular and non-cellular elements, serves as the first line of defense in the human body. The skin serves as a barrier against many potentially harmful chemicals, physical, and biological substances (Lee & Kim, 2022). As a reaction to inflammation, infection, injury, and other external stresses, a variety of cell types, such as macrophages, lymphocytes, monocytes, keratinocytes, and fibroblasts, trigger inflammation-related genes such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF) (Muire et al., 2020; Parameswaran & Patial, 2010). There are wide ranges of biological and cellular reactions that are triggered by TNF-α when stimulated, such as leukocyte migration and activation, fever, acute phase inflammation, apoptosis, and differentiation. Consequently, TNF-α regulates and activates pathogenic and therapeutic effects, necessitating strict regulation of its expression. TNF-α mRNA production increases noticeably in 10–20 minutes without the need for protein synthesis, indicating that the elements required to induce TNF-α expression are already present in non-stimulated cells (Zhao et al., 2020). Both transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanisms are involved in the complex production of TNF-α in the monocytic cell lineage (Parameswaran & Patial, 2010). An earlier study indicates that several nuclear factor binding elements, such as NFkB, EGR-1, CREB, C/EBPb, AP-1, and AP-2, mediate TNF-α transcription in response to multiple stimuli (Alberini, 2009).

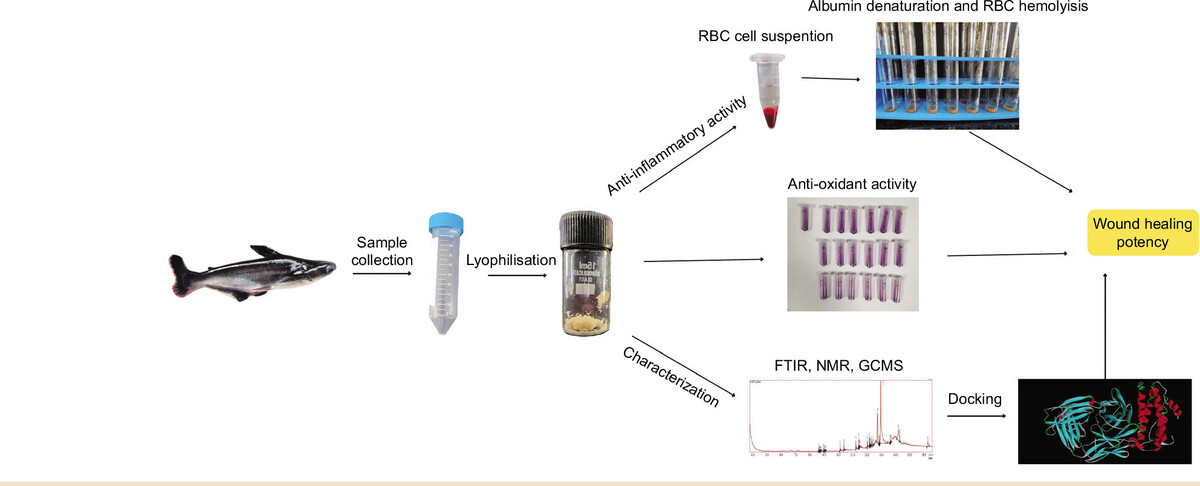

P. hypopthalmus is fast-growing freshwater teleost fish, popular worldwide for its taste, affordability, high protein content, omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid, and negligible carbohydrate content. It is known to improve cognitive function, heart health, and vision. Teleost fishes are known for fin regeneration, showing the natural potency of these fishes to induce cell division. In this regard, our current study is focused on evaluating the anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant activity of mucus from P. hypopthalmus for its therapeutic potential, followed by characterization studies using FTIR, NMR, and GC-MS analysis. Further, based on the compounds obtained from GC-MS analysis, docking is performed between the ligand and selective proteins to evaluate the necessity and mode of action.

2 METHODOLOGY

2.1. Sample collection and preparation

Five live fishes i.e P. hypopthalmus were collected from the Fisheries Research and Information Centre, Hesaraghatta, Bengaluru, Karnataka, and were reared under laboratory conditions as shown in our previous study (Gomathy & Pappuswamy, 2024). The test fishes were starved for 24 hours before collection and rinsed with 10% saline solution for sterilization. Mucus was collected aseptically from the dorsal side. Collection from the ventral side was limited to avoid anal contamination. The collected mucus was filtered and centrifuged to obtain a clear solution. The mucus was lyophilized to obtain a concentrated crude sample, which is used for further analysis. Lyophilized samples were prepared in different concentrations as test samples.

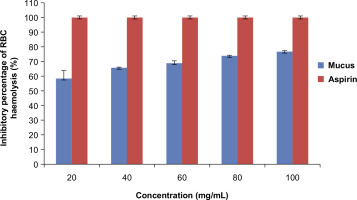

2.2. Red blood cell suspension preparation

In-vitro evaluation of the anti-inflammatory potency of mucus was assessed via RBC denaturation assay (Yesmin et al., 2020). Red blood cell membrane of humans act similar to cell’s lysosomal membrane. A healthy human volunteer was used for the donation of blood, with the main exclusion criterion being the use of NSAIDs within two weeks before the experiment. Na-oxalate was used as anticoagulant. Before being used, all blood samples were kept at 4 °C for 24 hours. Centrifugation was performed for five minutes at 2500 rpm using a saline solution of 0.9% w/v NaCl to separate the supernatant (plasma) and the remaining blood cells. The same process was repeated 3-4 times to determine the volume of the packed cells. For further reconstitution of cellular content, it was made up to a 10% suspension with normal saline solution.

2.3. Hemolysis assay

Hemolysis assay via induction of heat was carried out to evaluate the anti-inflammatory effect (Y.-P. Chen et al., 2018). A 50 µL of the cell suspension of RBC was added to each test tube, followed by the addition of 2 mL of 20 µL, 40 µl, 60 µL, 80 µL, and 100 µL concentrations of the lyophilized mucus into each test tube respectively (Sen et al., 2019). Water was used as blank solution. The test tubes were incubated at 54°C for 20 minutes in a water bath (Lala et al., 2020). The samples were centrifuged at 5000rpm for 5 minutes, followed by recording the absorbance of the supernatant at 560nm using a UV-visible spectrophotometer (SHIMADZU UV-1900). A 1000µg/mL concentration of aspirin was used as the reference drug. Water was used as the negative control. The percentage inhibition was evaluated according to the below formula.

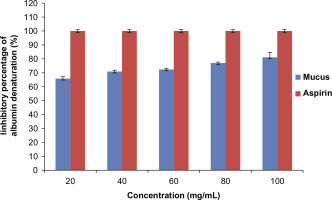

2.4. Albumin denaturation assay

Anti-inflammatory potential was also assessed by Albumin denaturation assay (Anokwah et al., 2022). Inflammation and arthritic diseases are caused due to the breakdown of protein and yielding of autoantigen. Thus, the biological agents showing the inhibition of protein breakdown can be utilized as an anti-inflammatory drug. The assay involved testing of lyophilized mucus of P. hypopthalmus against the breakdown of Bovine serum albumin protein. The reaction contained 1 mL of 1% BSA, 1 mL of saline phosphate buffer and 1 mL of test concentrations of 20 µg, 40 µg, 60 µg, 80 µg, and 100 µg of lyophilized mucus into respective test tubes. An equal volume of distilled water was used as the blank solution. Further, the sample was incubated at 37°C for 15 min, followed by heating at 70°C for 15 min in water bath (Yesmin et al., 2020). A 1000μg/mL concentration of aspirin served as the positive control. Absorbance (n=3) for all the samples was recorded at 660nm using a UV- Vis spectrophotometer (SHIMADZU UV-1900).

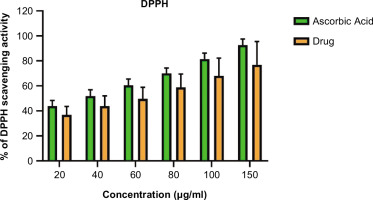

2.5. Anti-oxidant activity using DDPH assay

DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) assay (Baliyan et al., 2022) was performed to assess the anti-oxidant activity of fish mucus. Different concentrations of lyophilized fish mucus were prepared and 100 µL of each sample was mixed with 100 µL of DPPH solution (0.1 mM in methanol). Further the samples were incubated in the dark for about 30 minutes, and the absorbance of the samples was recorded at 517 nm. The standard used was ascorbic acid with 1mg/mL concentration. The absorbance was recorded using a spectrophotometer (SHIMADZU UV-1900). The percentage of free radical scavenging was calculated using the formula given below:

2.6. Statistical analysis

For statistical analysis, one-way analysis was used to determine the variation of anti-inflammatory activity of mucus at different concentrations. The probability of the statistical analysis was found to be p<0.05.

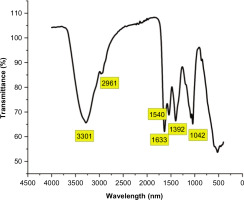

2.7. Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) analysis

FT-IR analysis was performed to identify the functional groups present in the lyophilized fish mucus (Cano-Trujillo et al., 2023). It was performed using SHIMADZU IR Spirit Fourier Transform Infrared Spectrophotometer. The spectrum was recorded within the wavelength range of 4000 cm–1 to 400 cm–1.

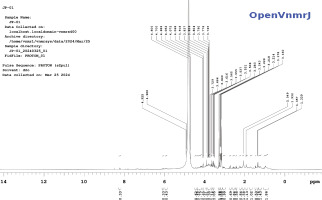

2.8 Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectral analysis

NMR spectral analysis (Stabili et al., 2019) was performed using a Nuclear Magnetic Resonance spectrophotometer. A 5 mg of lyophilized mucus of P. hyopophthalmus was dissolved in 500 µL of D2O. The sample was thoroughly mixed using a vortex for 5 min, centrifuged, and then transferred into the NMR tube. 1H NMR spectrum was recorded for the samples on a Bruker AVANCE III 500 MHz spectrometer using CDCl3 as the solvent and tetramethylsilane (TMS) as the internal standard. Chemical shifts (δ) are reported in parts per million (ppm). The raw data of the 1H NMR was processed using OpenVnmrJ, which is the open-sourced part of VnmrJ 4.2.

2.9. Gas chromatography–mass spectroscopic (GC-MS) analysis

Gas chromatography–mass spectroscopic analysis of the mucus was performed using two different extracts, i.e., hexane and chloroform, using SHIMADZU GCMS-QP2010 SE. Single Quadrupole GC-MS Willey and NIST libraries were used for compound identification, and their retention indices were compared.

2.10. Molecular docking

The target proteins IL-6, NF-kB, TNF-α, VEGF, P-53 were chosen for anti-inflammatory activity and wound healing were selected based on the existing literature review and the need for our current research. The crystallographic structures of the selected targets were acquired from the RCSB Protein bank data (https://www.rcsb.org/) . After retrieval of the targets, the proteins were prepared on Autodock 1.5.7 by removal of water molecules, addition of hydrogen atoms, and Kollman charges. Further, the grid value of all the targets was prepared using Autodock 1.5.7. The structure of the ligand was designed using Avogadro. Autodock 1.5.7 was used to convert the target to .pdbqt. Further docking was performed using Autodock 1.5.7 (Scripps Research Institute)(Trott & Olson, 2010). The results with the highest negative binding energy (obtained from scoring function) and conformation were chosen for analysis. PyMOL and Discovery Studio were used to visualize the docked structures (Lill & Danielson, 2011)

3. RESULTS

3.1. Anti-inflammatory assay

The anti-inflammatory potency of lyophilized mucus was tested by albumin denaturation and heat-induced RBC denaturation assay. Lyophilized mucus of P. hypophthalmus showed significant stabilization towards albumin denaturation assay at a concentration of 100mg/mL with an inhibition of 81% as shown in Figure 1. Also the percentage inhibition of RBC hemolysis was 76.79% at a concentration of 100mg/mL as shown in Figure 2. In addition, the inhibition percentage was calculated using aspirin as the reference drug. The results were statistically significant (p<0.05) as shown in Tables 1–4 of the supplementary data.

Table 1

Functional group analysis of FTIR analysis.

| SI. No. | Absorption | Group and Compound |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | 3301 | OH Stretching - Alcohol |

| 2. | 2961 | CH Stretching - Alkane |

| 3. | 1540 | NO - Nitro Compound |

| 4. | 1633 | C=C - Alkene |

| 5. | 1392 | OH - alcohol |

| 6. | 1042 | CO-O-CO - Anhydride |

Table 2

GCMS analysis of lyophilized mucus in chloroform extract.

Table 4

Therapeutic properties of compounds obtained from GC-MS analysis.

| Citation | Compound | Therapeutic Application |

|---|---|---|

| (Kim et al., 2013) | Heptadecane, | Antioxidant, Antiinflammatory |

| (Choi et al., 2020) | Undecane, 2-methyl | Anti-Allergic and Anti-Inflammatory |

| (Daly et al., 1999) | Decane, 2-methyl | antiangiogenic and amebicidal activity |

| (Tao et al., 2018) | Tricosane, 2-methyl | Antibacterial |

| (I. Ashraf et al., 2018) | Pentadecane, 2-methyl- | Antioxidant, antimicrobial |

| (Tyagi et al., 2021) | Sulfurous acid, dodecyl 2-propyl ester | Antioxidative |

| (Ghavam et al., 2021) | Nonadecane | antimicrobial |

| (Okechukwu, 2020) | Hexadecane | Anti-inflammatory, Analgesics,antipyretic |

| (Balachandran et al., 2023) | Eicosane | Antioxidant |

| (Mahmood et al., 2020) | Carbonic acid, nonyl vinyl ester | Anti-diabetic |

| (Achika et al., 2023) | Octadecane, 4-methyl- | Antioxidant |

| (Li et al., 2017) | Tricosane, 2-methyl- | Antibacterial |

| (Molele et al., 2023) | Nonadecane, 2-methyl- | Antimycotoxigenic |

| (Sales-Campos et al., 2013) | Oleic Acid | Anticancer, Antiinflammatory, wound healing |

| (Goyal et al., 2024) | Erucic acid | Antiinflammatory, antioxidant |

| (Sharath & Naika, 2022) | Z-8-Methyl-9-tetradecenoic acid | Antimicrobial, Antiinflammatory |

| (Vanitha et al., 2020) | Heneicosane, 11-(1-ethylpropyl)- | Antimicrobial |

| (Jones & Jew, 2024) | 1-Hexacosanol | Antipyretic, fungicidal, antihistamine, and antiseptic |

| (Makhafola et al., 2017) | n-Tetracosanol-1 | Antiinflammatory, antioxidant |

| (Stein & Cooper, 1988) | 1-Eicosanol | Antioxidant |

| (Alemu et al., 2015) | n-Nonadecanol-1 | Antiinflammatory,wound healing |

3.2. Antioxidant activity

The antioxidant activity was determined by evaluating its capacity to scavenge free radicals. The findings imply that the extract has potent radical-scavenging properties. The lyophilized mucus antioxidant activity increased correspondingly with increasing concentration of lyophilized mucus, as illustrated in Figure 3, the extract demonstrated 80% free radical scavenging activity at 150 µg/mL, compared against the standard ascorbic acid (p < 0.05).

3.3. FT-IR analysis

The obtained data from FT-IR analysis was interpreted using Origin Lab 2022 as shown on Figure 4. Absorption spectra of lyophilized mucus ranged from 4000-400 cm–1 as shown in the Table 1. The most intense band for OH ranged between 3550–3200 cm–1 indicating intra-molecular bonded alcohol group. The –CH, –CH2, –CH3 bonded Carbon and hydrogen was seen in the region of 2930-2980 cm–1, showing the characteristic feature of presence of carbohydrates, sugars, and alkane group. A sharp peak ranging between 1640–1620 cm–1 showed the presence of C=C thus representing the presence of di-substituted (cis) alkene and conjugated alkene. A strong peak at the range of 1530–1520 cm–1 was seen showing the bending of –NH indicating the presence of amine group and packing of proteins. The bending at the range of 1070–1020 cm–1 showed –CO–O–CO stretching, indicating the presence of anhydrate. The region ranging from 1400–900 cm-1 is called the finger print region as there is large number of characteristic peaks indicating the presence of specific functional groups. However, the chemical composition of the mucus was complex and the bands were overlapping thus not showing clear peaks, so the spectral thickness was increased to see only evident peaks. Since it is challenging to decode the components in the samples using FT-IR analysis, further analysis like NMR and GC-MS analysis was performed.

3.4. NMR analysis

From the NMR spectral analysis performed (Figure 5), visible and sharp peaks at 1.339, 1.357, 1.932 ppm were seen, thus indicating the presence of 1°, 2°, 3° alkane groups, 1° and 2° amines, and 1°, 2°, 3° alcohol groups. A sharp and visible peak was obtained at 2.049 ppm indicating the presence of alkyl groups. Peaks ranging between 3 and 4 ppm represented the presence of X–CH, –OH, –NH. Peaks ranging between 4 and 5 ppm showed the presence of nitro and phenol groups.

3.5. GCMS analysis

The prepared extract samples were aqueous extracts dissolved in hexane, lyophilized mucus dissolved in hexane, and lyophilized mucus dissolved in chloroform. Of these extracts, the chloroform extract showed the highest number of volatile organic compounds. Chloroform extract showed the presence of compounds present in both the other extract along with some new compounds, and hence the GC-MS extract of chloroform is reported here in Table 2. Forty-six volatile organic compounds were screened in the GC-MS analysis of chloroform extract, of which oleic acid was known to be present at a higher concentration of 46.77%, followed by Tris(2,4-di-tert-butylphenyl)phosphite at 13.81%, and tetraoxatricyclo[16.2.2.2(8,11)]tetracosa-1(20),8,10,18,21,23-hexaene-2,7,12,17-tetrone at 11.54%. Eicosane, Euric acid, hexadecanoic acid, Eicosanol, and Hexadecanoic acid were some other important compounds that were present and are known to have therapeutic effects.

3.6. Molecular docking

TP-53 was selected as it is a regulator gene for cell cycle pathway. Based on the GCMS analysis and Lipinski’s rule, the ligand (oleic acid) was selected. Molecular docking of oleic acid against the selected targets and binding energy are depicted in the Table 3. The most important interaction between the ligand and receptor is the one with the highest negative binding energy. The lowest binding energy was shown by TNF (-5.3kcal/mol). IL-6 showed only alkyl and van der Waals bonds, thus showing weak interaction. VEGF showed 3 hydrogen bonds with ASN V: 62, SER W: 50 and CYS V: 61 revealing the presence of strong interaction and structural modification. TNF showed two hydrogen bonds with SER A: 99 and GLU B:116 predicting strong interaction. NF-KB showed one hydrogen bond with ARG A: 56. Tp-53 showed two hydrogen bonds with SER B: 99 and ARG B: 267 with strong interaction. Thus, it is proven that oleic acid is binding with the inflammation target and wound healing target with high binding affinity.

4. DISCUSSION

Oleic acid is one of the commonly consumed monounsaturated fatty acids, and use of this compound as a therapeutic agent would be more compatible as it does not have known any side effects and is proven to have beneficial health effects when consumed orally. The application of oleic acid for therapeutic effects like wound healing would show a positive healing rate, as seen from the above analysis and as shown in our previous studies where L929 cells showed a migration rate of 99. 27%, thus paving the way for new discoveries (Gomathy & Pappuswamy, 2024).

The limited number of treatments for cutaneous inflammatory disorders like ICD, compromises their therapeutic utility and causes systemic and local side effects (Calabrese et al., 2022). One such treatment is the topical glucocorticoid medication dexamethasone, which is useful in treating skin inflammation but has side effects such as elevated blood pressure and hyperglycemia, slowed wound healing, reduced bone density, and water retention when used therapeutically (Poetker & Reh, 2010). In light of this, finding pharmaceutical alternatives that effectively treat skin inflammation while having fewer side effects is crucial (Mohd Zaid et al., 2022; Zeng et al., 2024).

When irritants come in contact with the skin, it defends itself by entering an inflammatory state, which helps the tissue to heal and restore itself (L. Chen et al., 2018). The onset of inflammatory symptoms such as erythema, oedema, heat, and discomfort are indicative of inflammation. These inflammatory symptoms cause skin cells to release a number of soluble mediators, including complement system proteins such as chemokines, cytokines, and vasoactive amines (Poetker & Reh, 2010). These mediators cause changes in the local vasculature, which intensify the inflammatory process by increasing blood flow, causing fluid to leak, and causing circulating cells to infiltrate surrounding tissue (Pober & Sessa, 2015).

Severe wounds and inflammation cause the loss of integrity of the skin, leading to its functional imbalance, disability, tissue death, or skin amputation in case of diabetes (Akkus & Sert, 2022). Hence, the research about wound healing and anti-inflammatory property of any biomaterial is of utmost priority for the benefit of human and veterinary medicine.

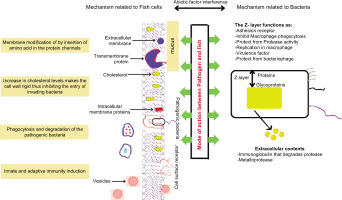

Recently, biomaterials have been studied for their various therapeutic properties, such as anti-microbial, anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory, and wound healing properties as shown in previous studies (Gomathy & Pappuswamy, 2024; Lopes et al., 2024). Almost all the biomaterials obtained from fishes are known to have therapeutic properties (Cruz et al., 2021; Tasleem et al., 2024). The current study was focused on exploring anti-inflammatory and therapeutic effects of the compounds present in the mucus. Inflammation and microbial resistance are the major obstructions in the phases of wound healing. The characterization results obtained from FTIR analysis indicated the presence of amino acids (by the presence of NH3 and OH groups), sugars, and carbohydrates. Further NMR also showed the presence of NH (amines) and OH groups, thus confirming the presence of amino acids and carbohydrates. Further, from GC-MS analysis, it is evident that all the 46 different compounds in the mucus that abided by Lipinski’s rule of 5 (as represented in Table 2), showed potential to be orally active drug. Apart from these results, the compounds also showed other therapeutic properties as shown in the Table 4.

Even after performing all of the above-discussed analysis, a clear structure of the components present in the fish mucus was not possible to identify. Hence, detailed investigations need to be performed for further application. From the GC-MS analysis, oleic acid was present at higher percentage compared to other compounds, which eventually induced anti-inflammatory activity, our research is on par with studies reported by Pegoraro et. al. (Pegoraro et al., 2021). TNF-α is an important protein involved in Anti-inflammatory process. TNF-α production is induced by monounsaturated (oleic acid) and PFA (linoleic acid) (Lima-Salgado et al., 2011). Studies on changes in poly(A) tail length, gene expression, and transcription factor activation have demonstrated that oleic and linoleic acids have anti-inflammatory properties and promote the cell’s TNF-α production in response to lipopolysaccharides (Belal et al., 2018). Saturated fatty acids have the ability to strongly stimulate TNF-α production and expression in both baseline and inflammatory environments (Hg et al., 2024). Docking results showed that there is high interaction between oleic acid and inflammation-related proteins. Thus, mucus of P. hypopthalmus could be a source of drug for inflammation-related disorder and the current study has laid the groundwork for further investigations.

5. CONCLUSION

From the previous studies performed, we conclude that the mucus of Pangasianodon hypopthalmus has wound healing potency (in-vitro) and anti-microbial activity. From the current study, we have concluded that it possesses anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant activity. Also, molecular docking studies revealed that TNF and IL6 proteins had good binding affinity toward oleic acid, which was characterized using GC-MS analysis. This biomaterial wound pave the way for a new solution to wound healing; however, further in-vivo studies have to be performed for complete understanding and gene expression.

6. ABBREVIATION

PFAs: Polyunsaturated fatty acids

BSA: Bovine serum albumin

EPA: Eicosapentaenoic acid

DHA: Docosahexaenoic acid

TNF- α: Tumor necrosis factor-α

NFkB: Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells

AP-1: Activator protein 1

EGR: estimated glomerular filtration rate

CREB: cAMP-response element binding protein

C/EBPb: enhancer binding proteins

AP-2: Activating enhancer binding Protein 2 alpha

BSA: Bovine serum albumin

DPPH: 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl

FTIR: Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy

NMR: Nuclear Magnetic resonance

GCMS: Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectroscopic

IL-6: Interleukin 6

VEGF: Vascular Endothelial Growth factor

ICD: Common Inflammatory disorder