1. INTRODUCTION

The oral cavity and its associated structures are essential for daily functions and play a crucial role in overall health. Most oral health problems are both preventable and treatable when detected early. Common oral diseases include halitosis, aphthous ulcers, oral infections, xerostomia, gingivitis, dental caries, and periodontal diseases. Other notable conditions affecting oral health include tooth loss, orofacial clefts, noma, and orodental trauma National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (2021).

Dental caries is known as a multifactorial condition characterized by biofilm development resulting from the prolonged fermentation of carbohydrates on the tooth surface. Its occurrence is affected by several factors, including host health, duration of exposure, consumption of carbohydrate-rich foods, and the presence of cariogenic bacteria. This condition negatively affects overall quality of life and oral health (Deviyanti et al., 2019; Basir et al., 2023). The prevalence of dental caries continues to increase annually, particularly in developing countries. One study reported that 61% of 696 children aged 12 years exhibited dental caries, with a mean score of decayed, missing, and filled teeth (DMF-T) is 1.58, and many lesions remained untreated (Maharani et al., 2019). According to the Ministry of Health (2018), the average DMF-T index among individuals aged 35–44 years was 6.9, reflecting a substantial burden of untreated cavities in this age group. Dental caries is considered the most common microbial disease in humans and is primarily driven by four key factors: oral bacteria, the oral environment, the host, and time. The pathophysiology of dental caries is further shaped by the complex synergistic and competitive interactions among Streptococcus mutans, Candida albicans, and Porphyromonas gingivalis (Chen et al., 2020).

Streptococcus mutans is widely recognized as a primary cariogenic bacterium due to its ability to ferment dietary carbohydrates into acids that demineralize tooth enamel, and its pathogenicity is further enhanced by C. albicans, which coexists with S. mutans to form a robust, highly virulent biofilm. Together, these microorganisms produce extracellular polysaccharides (EPS), particularly glucans, that promote strong adhesion to the tooth surface and contribute to biofilm stability and cariogenicity (Rahmah et al., 2020; Kim et al., 2021). C. albicans thrives in sugar-rich environments and increases biofilm acidity when cohabiting with S. mutans, thereby exacerbating caries severity (Lu et al., 2023; Huang et al., 2023), while the synergistic interaction between the two enhances overall biofilm virulence. In addition, P. gingivalis, although primarily associated with periodontal disease, can coexist within polymicrobial biofilms containing S. mutans and C. albicans, contributing to dysbiosis by modulating host inflammatory responses (Tangsuksan et al., 2022; Alam et al., 2024). The coexistence of these three pathogens strengthens the structural integrity and pathogenic potential of oral biofilm communities, creating significant challenges for caries prevention and management, particularly in vulnerable populations such as infants with Early Childhood Caries (ECC) (Lu et al., 2023). Although the antimicrobial properties of individual herbal extracts—such as ginger, mint, and green tea—are well established, limited research has investigated their combined effects in a single polyherbal mouthwash or assessed their activity against multi-species biofilms involving S. mutans, P. gingivalis, and C. albicans. Therefore, this study aims to formulate and characterize a polyherbal mouthwash (JaminTea) and evaluate its antibacterial and anti-biofilm efficacy in comparison with commercially available products such as chlorhexidine and Listerine.

Caries prevention can be achieved by employing antibacterial agents that inhibit biofilm formation. Brushing teeth twice daily with toothpaste is among the most common methods of plaque control; however, this practice alone is often insufficient, as food debris frequently remains in hard-to-reach areas (Moghaddam et al., 2022). Mouthwash therefore serves as a valuable adjunct to tooth brushing, yet many commercial formulations contain chemical compounds such as sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS), which may cause undesirable effects. This has increased interest in herbal mouthwashes, which offer antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant properties with potentially fewer adverse reactions (Biswas et al., 2014; Tabatabaei et al., 2020). Reported side effects of chemical-based mouthwashes include gingival irritation and oral dryness, while long-term use—particularly of chlorhexidine, considered the “gold standard” for plaque control—may lead to mucosal irritation, tooth staining, altered taste perception, and a burning sensation in the oral cavity (Reshawn & Muralidharan, 2021; Dahal et al., 2018). Therefore, identifying safer and more natural alternative cleaning agents is essential to minimize adverse effects while maintaining optimal oral health.

The use of herbal alternatives has gained increasing attention as a promising strategy in light of growing concerns regarding the adverse effects associated with chemical-based oral care agents. Herbal mouthwashes enriched with plant extracts exhibiting antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant properties have shown considerable potential (Brookes et al., 2023). Several natural substances are known for their notable antimicrobial activities, including ginger extract, mint leaf extract, and green tea extract. Previous study has demonstrated that ginger contains gingerol compounds with antibacterial effects against Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus sanguinis (Azizi et al., 2015), in addition to exhibiting inhibitory activity against Candida albicans and Candida krusei. Mint leaf extract has also shown antibacterial action against S. mutans (Muhtar et al., 2024). Similarly, epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), the major polyphenol in green tea, has been shown to exert antimicrobial properties effective against both Gram-negative and Gram-positive oral pathogens (Hattarki et al., 2021). Although the present study did not directly quantify these metabolites, their potential contributions are discussed based on existing literature. Despite extensive documentation of the antimicrobial effects of individual herbal extracts, limited research has explored their combined efficacy within a single mouthwash formulation, particularly against multispecies biofilms formed by S. mutans, P. gingivalis, and C. albicans. Therefore, this study aims to formulated and evaluated the herbal mouthwash “JaminTea,” composed of ginger, mint, and green tea extracts, and to investigate its antimicrobial and anti-biofilm activities against these key oral pathogens.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mouthwash formulation

JaminTea mouthwash was formulated in a facility compliant with Good Manufacturing Practices (CPOB) standards at PT Dizza, Bogor, West Java. The formulation process combined the ingredients listed in Table 1 in accordance with the company’s standard procedures. Once the product was prepared, it underwent evaluation for organoleptic properties and viscosity. The organoleptic assessment was performed through direct observation of the formulation, including color, taste, aroma, and overall appearance. A hedonic test was subsequently conducted, in which panelists evaluated three different JaminTea formulations and provided feedback. A small-scale preliminary assessment (n = 8) was carried out to gauge respondents’ perceptions of taste, color, texture, and aroma. Due to the limited sample size, no statistical analysis was conducted; instead, findings are presented descriptively to offer an initial overview of user acceptability. The viscosity of each formulation was analyzed using a Brookfield viscometer by immersing the spindle into the sample contained in a beaker glass and operating it at a speed of 60 rpm. The viscosity value was recorded once the reading stabilized (Stefani et al., 2023).

2.2. Antimicrobial assay with disk diffusion methods

Antimicrobial testing against S. mutans, P. gingivalis, and C. albicans were conducted using cotton swabs that soaked in standardized microbial suspensions, which were inoculated onto Mueller–Hinton Agar (MHA) (HIMEDIA, M173-500G) plates and incubated for 24 hours at 37 °C. Paper discs impregnated with the sample solutions were applied to the inoculated plates, with DMSO (Merck, 1.029.521.000), Listerine, and 0.2% chlorhexidine serving as control treatments. Following incubation, the inhibition zones surrounding each disc were calculated (Sugiaman et al. 2024; Fibryanto et al., 2025).

2.3. MIC, MBC activity of JaminTea mouthwash

The subsequent antimicrobial assessment began with preparing inocula for each fungus and bacterium using the direct colony suspension method prior to determining MIC and MBC values. Inocula were obtained by transferring colonies of S. mutans and P. gingivalis grown on MHA for 24 hours into Mueller–Hinton Broth or MHB from HIMEDIA(M391-500G), while C. albicans colonies were transferred into Potato Dextrose Broth (PDB) (HIMEDIA, M096-500G). The turbidity was calibrated to match the 0.5 McFarland standard (1–5 × 108 CFU/mL). MIC values were assessed utilizing 96-well microplates containing varying concentrations of JaminTea mouthwash (100%, 50%, 25%, 12.5%, 6.25%, and 3.13%) mixed with microbial cultures, followed by incubation for 24 hours at 37 °C. Chlorhexidine 0.2% (Minosep) served as the positive control, Listerine as the comparative control, 10% DMSO as the negative control, and the growth control consisted of fungi or bacteria in PDB alone. Turbidity was measured after incubation using a spectrophotometer at 500–600 nm. MBC values were determined by transferring 100 µL from each MIC well, performing serial dilutions (102–105), and plating 50 µL of each dilution onto MHA using the pour-plate technique. Plates were incubated for 24 hours at 37 °C, after which colony counts were conducted utilizing a colony counter from Funke Gerber (8500) (Ilangovan & Rajasekar, 2021; Sugiaman et al., 2024).

2.4. Biofilm assay

Biofilm experiments were conducted using Brain Heart Infusion Broth (BHI) from HIMEDIA (M120-500G). The turbidity of the bacterial suspension was adjusted to approximately the 0.5 McFarland standard (~108 CFU/mL). A volume of 50 µL of the standardized suspension was administered to sterile 96-well plates that contained 100 µL of JaminTea mouthwash. Negative controls contained 200 µL of BHI alone, while positive controls contained 0.2% chlorhexidine. The plates were incubated at 37 °C aerobically without agitation. After 24 hours, the supernatant was carefully removed, and each well was gently rinsed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Biowest X0520-500). The adherent biofilm was then stained with 125 µL of 0.1% crystal violet solution for 15 minutes at room temperature. Excess dye was rinsed off with distilled water, after which the plates were air-dried. The bound crystal violet was solubilized with 125 µL of 30% acetic acid (RLC2.0057.0500) per well, and the optical density (OD) of the resulting solution was measured at 570 nm (OD570) using a microplate spectrophotometer from Multiskan Go, Thermo Scientific (51119300) (Malhotra et al., 2011; Landeo-Villanueva et al., 2023; Sugiaman et al. 2024).

2.5. Data analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS (version 20.0) and are presented as mean ± standard deviation. The Shapiro–Wilk test and the Levene’s test were used to assess normality and homogeneity, respectively. Normally distributed data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA then Tukey’s HSD post hoc test, whereas non-normally distributed data were evaluated using the Kruskal–Wallis test then the Mann–Whitney U test. A significance level of p < 0.05 was applied.

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of JaminTea mouthwash

Organoleptic observations of the JaminTea mouthwash are summarized in Tables 2 and 3. Most respondents assigned a rating of “4,” indicating a favorable assessment for parameters such as color, taste, and aroma. In terms of viscosity, JaminTea exhibited values ranging from 1500 to 2000 cPs, with a measurement accuracy of 99.9%.

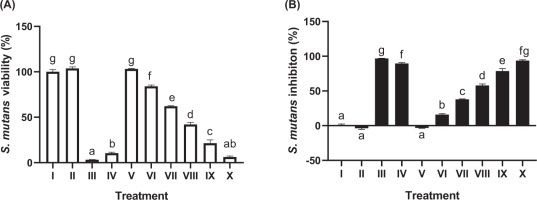

3.2. Antibacterial MIC & MBC activity in S. mutans

The antibacterial activity of JaminTea mouthwash against S. mutans is shown in Figure 1. The MIC, defined as the lowest concentration producing more than 50% bacterial inhibition, was identified at 25% JaminTea, with an inhibition rate of 57.88%. The 100% JaminTea solution demonstrated the highest inhibitory effect at 93.82%, slightly lower than the positive control (0.2% chlorhexidine, 96.81%) but higher than Listerine (89.62%). A clear dose-dependent response was observed, with increasing JaminTea concentrations resulting in stronger antibacterial activity (p < 0.05).

Figure 1

Effect of various concentrations of JaminTea mouthwash on the growth and inhibition of Streptococcus mutans. (A) Viability; (B) Inhibition.

*Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. For each treatment, testing was carried out in three repetitions. Different superscripts (a, ab, b, c, d, e, f, fg, and g) mark significant differences between various JaminTea mouthwash treatments (p<0.05, Tukey’s HSD test). Roman numerals Roman numerals I; growth control (MHB + bacteria); II: Negative control DMSO + bacteria; III: positive control chlorhexidine 0.2% + bacteria; IV: commercial mouthwash comparison control (Listerine + bacteria); V-X is a variation of JaminTea mouthwash treatment (3.125, 6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, and 100% + bacteria).

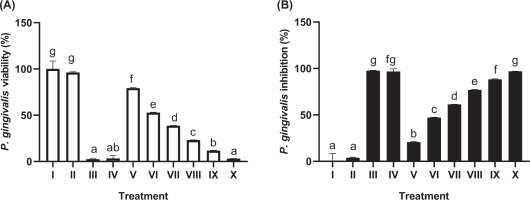

3.3. Antibacterial MIC & MBC activity in P. gingivalis

The effects of JaminTea on P. gingivalis are presented in Figure 2. The MIC was identified at a 25% concentration, yielding an inhibition rate of 60.31%. The 100% JaminTea solution produced an inhibition rate of 92.40%, closely approaching that of chlorhexidine (95.89%) and exceeding the inhibitory effect of Listerine (87.55%). These findings demonstrate substantial antibacterial activity of JaminTea, particularly at higher concentrations (p < 0.05).

Figure 2

Effect of JaminTea mouthwash concentrations on P. gingivalis viability (A) and inhibition (B).

*Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. For each treatment, testing was carried out in three repetitions. Different superscripts (a, ab, b, c, d, e, f, fg, and g) mark significant differences between various JaminTea mouthwash treatments (p<0.05, Mann-Whitney test). Roman numerals I; growth control (MHB + bacteria); II: Negative control DMSO + bacteria; III: positive control chlorhexidine 0.2% + bacteria; IV: commercial mouthwash comparison control (Listerine + bacteria); V-X is a variation of JaminTea mouthwash treatment (3.125, 6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, and 100% + bacteria).

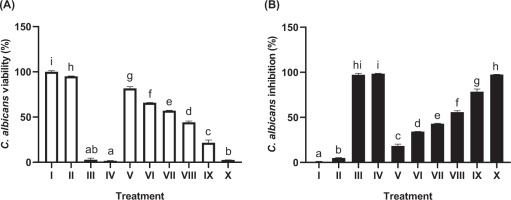

3.4. Antibacterial MIC & MBC activity in C. albicans

The study evaluated the effect of JaminTea mouthwash on C. albicans, a fungal pathogen associated with oral and dental diseases (Figure 3). The MIC, defined as the lowest concentration achieving more than 50% inhibition, was observed at 25% JaminTea, yielding an inhibition rate of 55.86%. The highest concentration (100%) produced a kill rate of 97.46%, comparable to chlorhexidine (97.14%) and a commercial mouthwash (98.44%), with no significant difference in efficacy (p < 0.05). As shown in Table 4, higher concentrations of JaminTea markedly reduced fungal growth, whereas lower concentrations had minimal effect. Overall, JaminTea demonstrated strong inhibitory activity against C. albicans, similar to that of standard controls. Microdilution assays further confirmed that both MIC and MBC values of JaminTea varied depending on the microorganism tested, with higher concentrations consistently reducing colony-forming units (CFUs) across all strains.

Table 4

Colony count results for the bacteria and fungi tested.

Figure 3

Effect of JaminTea mouthwash concentrations on C. albicans viability (A) and inhibition (B).

*Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. For each treatment, testing was carried out in three repetitions. Different superscripts (a, ab, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, hi and i) mark significant differences between various JaminTea mouthwash treatments (p<0.05, Mann Whitney test). Roman numerals Roman numerals I; growth control (PDB + C. albicans fungus); II: Negative control DMSO + C. albicans fungus ; III: positive control chlorhexidine 0.2% + C. albicans fungus; IV: commercial mouthwash comparison control (Listerine + C. albicans fungus); V-X is a treatment variation of JaminTea mouthwash (3.125, 6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, and 100% + C. albicans fungus).

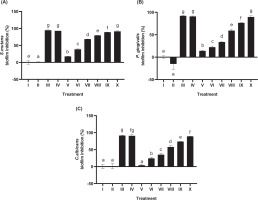

3.5. Zone inhibition activity

Disk diffusion testing assessed the inhibitory activity of JaminTea mouthwash against three oral pathogens (Figure 4A–C). For S. mutans, the smallest inhibition zone was 1.04 mm at the 6.25% concentration, whereas the largest zone measured 14.33 mm at 100%. P. gingivalis exhibited inhibition zones ranging from 2.23 mm at 12.5% to 14.21 mm at 100%. In contrast, C. albicans demonstrated a narrower inhibition range, with the smallest zone measuring 1.66 mm at 12.5% and the largest at 8.14 mm at 100%. Among the tested microorganisms, S. mutans and P. gingivalis exhibited the greatest overall inhibition. All results showed statistically significant differences compared to the controls (p < 0.05), and lower concentrations of JaminTea were generally classified as resistant.

Figure 4

Effect of various concentrations of JaminTea mouthwash on inhibition zone formation. (A) S. mutans; (B) P. gingivalis; (C) C. albicans.

*Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. For each treatment, the test was performed in three repetitions. Different superscripts (a, ab, b, bc, c, d, e, ef, and f) mark significant differences between different treatments of JaminTea mouthwash (p<0.05, Tukey’s-HSD). Roman numeral I: DMSO negative control; II: chlorhexidine 0.2% positive control; III: commercial mouthwash comparison control (Listerine); IV-IX are the various treatments of JaminTea mouthwash (3.125, 6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, and 100%).

3.6. Biofilm activity of JaminTea mouthwash

Biofilm formation by the three microorganisms was evaluated as shown in Figure 5A–C. The results indicate that increasing concentrations of JaminTea mouthwash produced substantial inhibitory effects on all tested organisms. S. mutans demonstrated the greatest reduction in biofilm formation at 91.31%, followed by P. gingivalis at 89.53% and C. albicans at 89.05%. The biofilm inhibition observed across all microorganisms showed statistically significant differences among treatment groups (p < 0.05); however, the inhibition achieved at higher JaminTea concentrations did not differ significantly from the drug control or the Listerine comparison control, indicating comparable anti-biofilm effectiveness.

Figure 5

Effect of various concentrations of JaminTea mouthwash on biofilm formation. (A) S. mutans; (B) P. gingivalis; (C) C. albicans.

*Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. For each treatment, the test was performed in three replicates. Different superscripts (a, ab, b, bc, c, d, e, ef, and f) indicate significant differences between various treatments of JaminTea mouthwash (p<0.05, Mann-Whitney). Roman numerals I; growth control; II: DMSO negative control; III: 0.2% chlorhexidine positive control; IV: commercial mouthwash comparison control (Listerine); V-X are variations of JaminTea mouthwash treatments (3.125, 6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, and 100%).

4. DISCUSSION

The rising incidence of oral disorders, particularly those caused by pathogenic microorganisms such as S. mutans, P. gingivalis, and C. albicans, has heightened interest in alternative approaches to oral health management. One widely used option is mouthwash containing 0.12% chlorhexidine, which has been shown to effectively reduce plaque index (PI) and gingival index (GI) (Amoian et al., 2017). However, concerns regarding the side effects associated with synthetic compounds have driven a growing preference for herbal-based mouthwashes. These formulations provide antimicrobial benefits derived from natural ingredients while minimizing the adverse reactions commonly linked to conventional products (Chatzopoulos et al., 2022). In this context, the present study aimed to formulate and evaluate a polyherbal mouthwash designed to suppress microbial activity associated with dental and oral diseases.

The formulated mouthwash was evaluated for its organoleptic characteristics and viscosity profile. Positive organoleptic assessments (Table 2) indicate good acceptability of the formulation in terms of color, taste, and aroma. Viscosity, an important parameter influencing both product efficacy and user comfort, was also assessed. Ideally, mouthwash viscosity should approximate that of water (~1 cP) to ensure ease of use during rinsing (Stefani et al., 2023). As shown in Table 3, viscosity measurements at the highest RPM level yielded values approaching this standard, approximately ±1 cP. Previous studies have reported viscosity values for herbal mouthwash formulations ranging from 1.5 to 3.5 cP. For example, formulations containing Zingiber officinale var. officinale demonstrated viscosities between 3.03 and 3.50 cP (Stefani et al., 2023), whereas another study documented values ranging from 1.69 to 2.35 cP (Bokhare et al., 2020). Beyond viscosity, the active ingredients also play a critical role in determining mouthwash effectiveness. Chlorhexidine, although widely regarded as the standard reference due to its potent antimicrobial activity, is associated with adverse effects such as tooth staining and altered taste perception (Tartaglia et al., 2019). Herbal mouthwashes, by contrast, have exhibited antimicrobial efficacy comparable to chlorhexidine without these negative effects, making them promising alternatives (Pathan et al., 2017; Gupta et al., 2018). Moreover, studies have shown that herbal formulations can achieve satisfactory viscosity and stability while maintaining antimicrobial effectiveness against common oral pathogens (Pathan et al., 2017; Gupta et al., 2018). Jain et al. (2023) further noted that variations in herbal mouthwash viscosity may result from differences in formulation processes, particularly the selection of excipients and extraction methods, which significantly influence the physical properties of the final product.

This study employed chlorhexidine mouthwash as the positive control for antibacterial efficacy, while DMSO and untreated bacterial cultures served as negative controls. Listerine, a commercially available herbal mint mouthwash in Indonesia, was also included as a comparative control. The antimicrobial activity of the JaminTea extract was demonstrated through laboratory-based experimental assays that evaluated its antibacterial effectiveness across various concentrations. JaminTea effectively inhibited the growth of S. mutans (Figure 1), P. gingivalis (Figure 2), and C. albicans (Figure 3), with minimum inhibitory concentrations for these microorganisms ranging between 12.5% and 25%. A previous study by Khobragade et al. (2020) reported an MIC of 0.2 mg/mL for herbal mouthwashes containing ginger and mint, along with inhibition zone diameters of 18 mm for S. mutans and 20 mm for P. gingivalis. In the present study, the inhibition zones for these bacteria showed slight variations despite the inclusion of both ginger and mint in the JaminTea formulation (Figures 4A–B). Nonetheless, these findings collectively underscore the promising antibacterial potential of mouthwashes containing ginger and mint, particularly when combined with additional herbal components. Ahmed et al. (2022) further demonstrated the strong antimicrobial activity of ginger against selected oral microbes, particularly S. mutans, the primary etiological agent of dental caries, reporting very low MIC values. Similarly, Eslami et al. (2015) highlighted the antibacterial effectiveness of ginger mouthwash when compared to nystatin in treating denture stomatitis, reinforcing its capacity to achieve favorable MIC values against oral pathogens.

Biofilm inhibition was clearly demonstrated in Figure 5, showing a dose-dependent effect across all tested microorganisms. No significant differences were observed between JaminTea and the comparative controls, Listerine and 0.2% chlorhexidine. Previous study by Fibriyanto et al. (2025), which demonstrated that a mouthwash formulated with elephant ginger extract exhibited greater efficacy than 0.1% chlorhexidine in reducing S. mutans biofilm at concentrations of 5% and 10%. Additionally, Antunes et al. (2015) confirmed that green tea–based mouthwash inhibited C. albicans biofilm formation by 17.06%. The dose-dependent inhibition observed in the present study can be attributed to the increased availability of bioactive compounds at higher concentrations, enabling more effective penetration of the biofilm matrix and enhanced interaction with embedded microbial cells. This disrupts the biofilm’s protective mechanisms, resulting in greater structural damage and reduced viability (Fernández-Billón et al., 2023).

The antibacterial mechanisms of ginger, mint, and green tea extracts involve multiple bioactive compounds working synergistically to inhibit bacterial growth and virulence through various molecular pathways. In ginger extract (Zingiber officinale), key active compounds such as gingerol, shogaol, and essential oils (e.g., linalool, geraniol, citral) are known to disrupt bacterial cell membranes (Zhang et al., 2022). This disruption increases membrane permeability, leading to the cellular contents leakage including electrolytes, nucleic acids, proteins, ATP, and exopolysaccharides, ultimately causing cell death (Endrini, 2024). Furthermore, Juariah et al. (2023) used electron microscopy to demonstrate morphological changes in bacterial cells, such as membrane wrinkling and damage after treatment with ginger extract. The extract also inhibits key bacterial enzymes, including succinate dehydrogenase and alkaline phosphatase, disrupting cellular metabolism and causing protein denaturation and cytoplasmic membrane damage (Juariah et al., 2023). These antibacterial effects are bactericidal and dose-dependent, with high effectiveness particularly against Gram-negative bacteria including P. gingivalis (Mohammed et al., 2019).

Meanwhile, mint extract (Mentha spp.), rich in compounds such as menthol, menthone, and terpenoids (Ćavar Zeljković et al., 2021), exhibits antibacterial activity through similar mechanisms. These active chemicals compromise bacterial membrane integrity, alter intracellular enzymatic systems, and obstruct bacterial cell-to-cell communication or quorum sensing, which is essential for biofilm formation and virulence regulation (Kang et al., 2019). By interfering with these processes, mint significantly diminishes bacterial colonization and pathogenicity (Kaur et al., 2020). Green tea extract (Camellia sinensis), containing catechins, especially epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), also demonstrates significant antibacterial activity (Abd El-Hack et al., 2020). EGCG disrupts bacterial cell membranes, increases their permeability, and inhibits key enzymes in DNA replication and bacterial metabolism (Zhang et al., 2023). Additionally, polyphenols in green tea can chelate essential metal ions, restricting bacterial growth by reducing nutrient availability (Chaudhary et al., 2023). Green tea has been demonstrated to impede biofilm development, thereby diminishing bacterial adhesion and colony establishment, which are generally resistant to therapy (Emara et al., 2025).

In addition to these three primary components, the mouthwash formulation also contains Centella asiatica and Piper betle leaf extracts. Centella asiatica is widely recognized for its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, wound-healing, and antimicrobial properties, particularly in relation to skin and mucosal repair (e.g., madecassoside and asiatic acid stimulate collagen synthesis and epithelial proliferation) (Diniz et al., 2023). Piper betle has been demonstrated to exhibit strong antimicrobial and antibiofilm activity against oral pathogens, such as S. mutans and C. albicans, primarily due to active phytochemicals such as hydroxychavicol and 4-allylpyrocatechol (MIC values around 0.5–1 mg/mL, significant biofilm inhibition) (Phumat et al., 2020). Although this study did not assess their individual effects, their presence in the formulation likely contributes to the observed antimicrobial activity via synergistic mechanisms. Future research should evaluate their specific roles within multi-herbal combinations.

Overall, these three herbal extracts demonstrate strong potential as natural antibacterial agents, acting through various mechanisms that target essential bacterial structures and functions. This makes them promising alternatives to synthetic antimicrobial agents. Previous studies combining these extracts into a single mouthwash formulation have also shown significant antibacterial activity, particularly in the prevention of dental caries and the maintenance of oral hygiene. The limitation of this research is that the mouthwash formulation was prepared in collaboration with PT Dizza Herbal Indonesia. Due to proprietary restrictions, the exact percentage composition of individual ingredients could not be disclosed. Nevertheless, the formulation includes ginger, green tea, and mint extracts as its active ingredients, each of which has been widely reported to exhibit antimicrobial activity. While the JaminTea formulation demonstrated promising antibacterial and antibiofilm properties, further studies, including cytotoxicity testing on human cells, are needed to evaluate its safety and potential for clinical use. However, further studies are still required, particularly cytotoxicity assessments through in vivo and clinical research.

5. CONCLUSION

The JaminTea mouthwash, formulated with ginger, mint, and green tea extracts, has demonstrated strong antibacterial potential as a post-brushing oral hygiene aid, as evidenced by MIC-MBC determinations, inhibition zone measurements, and biofilm assays. To further support its development as an effective herbal mouthwash, comprehensive studies, particularly cytotoxicity evaluations, in vivo investigations, and clinical trials, are necessary.