1. INTRODUCTION

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a systemic autoimmune disorder, persistent in nature, and the exact cause of the disease is not yet determined but is mainly driven by a combination of genetic vulnerability and environmental factors. It typically impacts the small joints in the wrists, hands, and knees, leading to stiffness and swelling, and ultimately, progression leads to joint damage. Persistent synovitis results in the formation of pannus, a proliferative synovial tissue that invades surrounding cartilage and bone, causing cartilage degradation, bone erosion, and ultimately joint deformity and functional disability if left untreated (Karmakar et al., 2010; Ostrowska et al., 2018; Panagopoulos & Lambrou, 2018). Nearly 17.6 million people worldwide were living with RA in a 2020 report. The age-standardized global prevalence of RA is estimated at 208.8 cases per 100,000 population, accompanied by a mortality rate of 0.47 per 100,000 and a disability-adjusted life year (DALY) rate of 36.4 per 100,000. Smoking accounts for approximately 7.1% (95% uncertainty interval: 3.6%–10.3%) of RA-related DALYs. By 2050, the global number of people affected by RA is expected to rise to 31.7 million (with a 95% uncertainty interval of 25.8–39.0 million) (Black et al., 2023).

Individuals with RA often face a significant burden of comorbid conditions, which greatly affect their quality of life and make disease management more challenging. A systematic review and meta-analysis study indicates that the most prevalent comorbidities in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) are anxiety disorders (62.1%), hypertension (37.7%), and depression (32.1%). The presence of multiple comorbidities is linked to worse health outcomes, including higher disease activity, increased pain, and diminished physical function (Hill et al., 2022). Findings from various studies suggest that depression is a frequent comorbid condition in RA, with prevalence ranging from 14% to as high as 48% (Panagopoulos & Lambrou, 2018). There is a suggestion that depression may occur not only in patients affected by acute pain and disability related to RA despite a stable or improving inflammatory condition, but that in cases of RA affected by depression, there may also be an increase in inflammatory activity and poor treatment adherence. These patients show increased healthcare utilization and a higher risk of death (Fakra & Marotte, 2021; Ionescu et al., 2024). Given these factors, it is clear that healthcare providers should not only manage RA holistically but also consider and address mental health illnesses as part of routine RA patient care to improve overall healthcare outcomes and quality of life.

To prevent the relapse of RA in patients, the current treatment options known to suppress synovial inflammation and the progression of joint destruction are continued throughout the condition (Smolen et al., 2016). The diagnosis is often based solely on clinical findings, as the pattern and characteristics of joint involvement usually enable a reliable assessment of the patient’s condition. The presence of autoantibodies (e.g. rheumatoid factor, anti-citrullinated peptide autoantibodies [ACPAs]) and/or markers of systemic inflammation (e.g. elevated densitometric rate of erythrocytes and/or the presence of C-reactive protein) are supportive of a diagnosis but are unnecessary for diagnosis (Van Der Woude & Van Der Helm-van Mil, 2018).

Within the established animal models of RA, the adjuvant-induced arthritis (AIA) model is considered one of the most commonly utilized standard arthritis models. It shares many clinical features with human RA, including inflammation and swelling in the joints, synovial proliferation, and damage to cartilage and bones. The model was first developed based on the observation that certain strains of rats develop arthritis upon being injected with Complete Freund’s adjuvant (CFA). Hence, this model has been widely used in preclinical studies to understand the mechanisms of antirheumatic drugs and predict toxicity. Indicators such as paw thickness, clinical score, body weight, inflammatory markers, histopathology, and pain assessments are utilized for the evaluation of drugs (Bendele, 2001). Although there is currently no remedy for RA, various therapeutic strategies are available to manage its signs and symptoms. Present-day treatment approaches continue to rely on conventional pharmacologic agents, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), glucocorticoids, and disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs)—which include traditional synthetic DMARDs, biological DMARDs, and targeted synthetic DMARDs (Buttgereit et al., 2005; Smolen et al., 2020). Glucocorticoids, or corticosteroids, are frequently utilized to treat autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. Their strong anti-inflammatory activity makes them essential in treating RA (Buttgereit et al., 2005).

Though there are now increased options for pharmacotherapy in RA, there are still limitations to current treatments. Many patients fail to achieve complete respite, and prolonged use of DMARDs and biologics may lead to significant adverse effects, such as severe infections with herpes zoster virus and tuberculosis, along with the possibility of developing melanoma. The conventional remedies of NSAIDs or joint surgery to alleviate inflammation and pain also take a toll on patients’ mental health. The high cost of biologic agents imposes a substantial economic burden on both patients and healthcare systems (Kvien & Heiberg, 2003; Singh et al., 2016).

Considering these challenges, the focus has shifted to complementary and alternative approaches such as Ayurveda. Ayurveda, an ancient Indian medical system, emphasizes the therapeutic use of natural plant-based products and is recognized for its favorable safety profile and potential efficacy. Herbal formulations are increasingly valued by both clinicians and patients due to their minimal side effects and potential to enhance conventional therapies. As an adjuvant treatment strategy for RA, Ayurvedic medicine may offer a holistic approach that improves efficacy while reducing toxicity. The plants selected for the current study viz., Boswellia serrata, Vitex negundo, Zingiber officinale, Ricinus communis, Curcuma longa, and Cannabis sativa, are individually well-known Ayurvedic medicines advised against inflammation and RA. Boswellia serrata extract has been reported to show improvement in body weight and reduced ankle diameter with a low arthritic index at a dose of 180 mg/kg (Kumar et al., 2019). One study by Zheng et al. (2014b) showed that the seeds of Vitex negundo were able to reduce the levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 while increasing that of IL-10 in serum for rats induced with arthritis. In a review by Al-Nahain et al. (2014), Zingiber officinale demonstrated significant anti-arthritic activity. Similarly, Hussain et al. (2021) reported anti-inflammatory activity of Ricinus communis in an RA rat model. Curcuma longa, in a review by Kou et al. (2023), established its role in reducing inflammation, while Cannabis sativa is a known analgesic that reduces pain (Boggs et al., 2016). Hence, our aim in this study is to develop and investigate ArthoCan-V50, a polyherbal formulation of these six plants, by following Ayurvedic principles for the management of RA.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Chemicals and reagents

Diclofenac sodium [Batch No. DP-2298; Exp. June 2025; manufactured by Aagya Biotech Pvt. Ltd.] was procured from the local market and used as the reference standard anti-inflammatory drug. ArthoCan-V50 tablets were provided by Sudhatatav Pharmacy, Pune, India. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits for tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α; CAS No. KB3145) and interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β; CAS No. KLR0119) were obtained from KRISHGEN BioSystems, Mumbai, India. All other chemicals and reagents used were of analytical grade and purchased from reputable commercial suppliers.

2.2. Test Formulation: ArthoCan-V50

ArthoCan-V50 is a polyherbal formulation developed by Sudhatatva Pharmacy, Dr. D. Y. Patil College of Ayurveda and Research, Pimpri, Pune (Figure 1). It is made up of extracts from six medicinal plants that are traditionally used in Ayurveda for the management of arthritis and inflammatory conditions: Boswellia serrata (Shallaki), Vitex negundo (Nirgundi), Zingiber officinale (Shunthi), Ricinus communis (Erandamoola), Curcuma longa (Haridra), and Cannabis sativa (Vijaya). The plant components and their quantities used per tablet are listed in Table 1. Although these herbs have long been used traditionally, the safety and efficacy of this particular combination are yet to be determined by systematic preclinical research. Therefore, the present study was designed to examine the toxicity profile and anti-arthritic activity of ArthoCan-V50 using standard laboratory models.

2.3. Assessment of in vivo anti-arthritic effects using the CFA-induced paw edema model

Wistar rats (200–250 g) were housed in standard (28 × 21 × 14 cm; five per cage) opaque polypropylene cages provided with dust-free paddy husk as bedding material. The 12-h light/dark cycle was maintained in the registered animal house (198/PO/Re/S/2000/CPCSEA) of Dr. D. Y. Patil Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research, Pimpri, Pune-411018. Feed and water were provided ad libitum. The room temperature was maintained at 22 ± 5°C with relative humidity (50–70%).

All experimental procedures were carried out in accordance with the guidelines provided by the Committee for the Purpose of Control and Supervision on Experiments on Animals (CPCSEA Reg. No. 198/PO/Re/S/2000/CPCSEA) and were approved by the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee (Protocol No. DYPIPSR/IAEC/Nov/23-24/P-04).

2.4. Acute toxicity study

The acute oral toxicity study was performed following OECD Guideline 423 (Acute Toxic Class Method) to assess the safety profile of ArthoCan-V50 (OECD, 2002). The animals were fasted overnight (approximately 12 h) prior to dosing with ArthoCan-V50, but water was provided freely. The ArthoCan-V50 tablet was administered orally in a single dose of 2000 mg/kg body weight, as per the limit test protocol of OECD 423. The detailed protocol is listed in Table 2 below.

Table 2

Treatment protocol for acute oral toxicity study.

| Sr. no | Group | Treatment | No. of animals |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Normal control | Vehicle 1ml p.o | 03 Female rats |

| 2 | Test | 2000 mg/kg p.o | 06 Female rats |

| Total | 09 |

During the first 30 minutes post-dosing, individual animals were observed, followed by periodic observations during the first 24 hours, with special attention during the first 4 hours. Subsequent observations were made daily for 14 days to monitor clinical signs of toxicity; changes in behavior, locomotion, skin, fur, eyes, and mucous membranes; and functions of the respiratory, circulatory, and central nervous systems (Gad, 2016; OECD, 2002).

On the 15th day, gross necropsy was performed to observe abnormal morphological changes in vital organs (liver, kidney, heart, spleen, brain, adrenal, ovaries, lungs), and the organs were stored in 10% neutral formalin solution. In cases where abnormal morphological changes were observed, the affected organs were submitted for further histopathological examination (Rocha-Pereira et al., 2019).

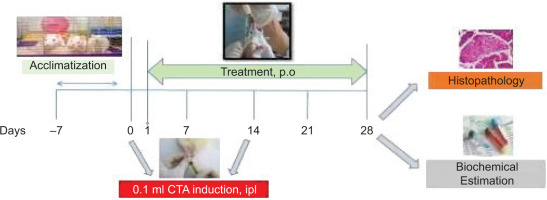

2.5. Induction of Arthritis and Experimental Design

Adult Wistar rats weighing 200–250 g were randomly divided into six groups, with eight animals per group (Table 3). Rheumatoid arthritis was induced using CFA. On day 0, rats in the arthritic groups received an injection of 150 μL CFA into the left hind paw, while the normal control group received 150 μL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). A booster dose of 150 μL CFA was administered on day 14 via intraplantar injection into the same paw to enhance arthritic symptoms. The normal control group again received 150 μL of PBS on the same day. The dosages of 50, 100, and 200 mg for ArthoCan-V50 were selected based on the data obtained from the acute toxicity study conducted prior to the induction of RA. All animals were anesthetized after the completion of the experimental period on day 28, and blood and tissue samples were collected for biochemical and histopathological analyses.

Table 3

Representation of different treatment groups for study.

An overview of the study design is depicted in the following schematic (Figure 2).

2.5.1. Clinical observations

All animals were observed daily for clinical signs of toxicity, behavioural changes, and mortality, if any, throughout the study period.

2.5.2. Food and water intake

Food and water consumption were measured on alternate days for all groups until day 28, prior to sacrifice. Intake was recorded to assess general health and treatment tolerance.

2.5.3. Body weight monitoring

The body weight of all animals was recorded every other day throughout the experimental period, up to day 28, to monitor changes related to disease progression or treatment effects.

2.5.4. Measurement of ankle joint and paw thickness

The thickness of both the injected and non-injected hind limbs was measured using a digital Vernier calliper (Zhart). Measurements were taken daily post-CFA administration, specifically above the ankle joint and at the paw. Each rat’s leg was gently restrained during measurement. The mean change in thickness compared to initial baseline values was calculated, and comparisons were made against the untreated control group.

2.5.5. Serum analysis

At the end of the study (day 28), animals were anesthetized, and blood samples were collected. Serum was separated and analysed for inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α and IL-1β, using ELISA kits (KRISHGEN Biosystems). Additional markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and rheumatoid factor (RF) were evaluated by PreclinBio Solutions, Pune.

2.5.6. Assessment of antioxidant parameters

Ankle joint tissues were excised post-sacrifice, weighed, and stored at –80°C. A 10% tissue homogenate was prepared in phosphate-buffered saline and analysed for antioxidant markers, including superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione (GSH), catalase (CAT), and malondialdehyde (MDA), using standard biochemical methods.

2.5.7. Histopathological examination

On day 28, animals were sacrificed, and hind limbs were dissected and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin. Bone and joint tissues from all groups (Group 1 to Group 6) were processed using standard histological techniques, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 3–5 µm, and stained with haematoxylin and eosin. Histopathological analysis was performed by a board-certified toxicopathologist to assess joint inflammation and tissue architecture.

2.6. Statistical analysis

All data were compiled in Microsoft Excel and analysed using GraphPad Prism software (version 8). One-way ANOVA followed by multiple comparison tests was used to evaluate statistical significance. Results were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Comparisons were made between treatment groups and both the normal and standard control groups. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. ArthoCan-V50 tablets assessment

Evaluating the physical properties of ArthoCan-V50 is essential to ensure that the formulation is uniform, stable, and reliable. Consistency in its appearance and sensory qualities, such as taste or smell, helps make it more acceptable to users. At the same time, meeting key quality control standards such as pH, hardness, and disintegration time ensures that the formulation performs as expected in terms of its pharmaceutical quality. Tables 4 and 5 provide confidence that the formulation is ready for preclinical testing, offering a solid foundation of quality before progressing to studies on toxicity and its anti-arthritic effects.

Table 4

Physical Characteristics of the Tablet.

Table 5

Quality Control Test for ArthoCan-V50.

3.2. Acute toxicity study

The ArthoCan-V50 tablets were subjected to acute toxicity testing in Wistar rats, and the animals were monitored for 14 days. Based on these findings, the acute oral toxicity study confirmed the safety of ArthoCan-V50 tablets, with no significant adverse effects observed at 2000 mg/kg. Therefore, doses of 50, 100, and 200 mg for 200 g Wistar rats were chosen for the present study.

3.3 Assessment of in vivo anti-arthritic effects using the CFA-induced Paw Edema model

The progression of arthritis was evaluated using various parameters, which were described in detail along with their corresponding statistical analyses.

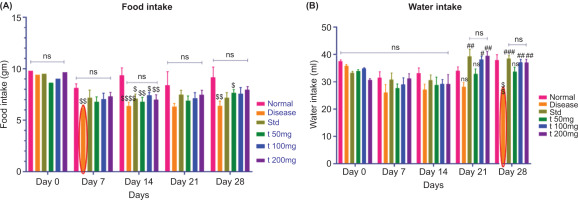

3.3.1. Food and Water Intake

Figure 3A represents the food intake recorded daily throughout the study. A significant reduction in food intake was observed in the CFA-treated (disease control) group. In contrast, animals treated with the standard drug (diclofenac) and the test formulation showed a significant increase in food intake compared to the disease control group. As water intake was recorded daily throughout the study, a significant decrease in water consumption was observed in the CFA-treated (disease control) group. In contrast, animals treated with the standard drug (diclofenac) and the test formulation exhibited a significant increase in water intake compared to the disease control group (Figure 3B).

Figure 3

(A,B): Effect of ArthoCan-V50 tablets on Food and Water intake in CFA induced RA in Wistar rats.

All values are expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 8, using Two-Way Multiple Comparison. For panel A, the normal group is compared with the disease, standard, and all test groups ($P<0.05, $$P<0.01, $$$P<0.001, $$$$P<0.0001, ns: non-significant). The disease group is compared with the normal, standard, and all treated groups (ns: non-significant). The standard group is compared with all test groups (ns: non-significant). For panel B, the normal group is compared with the disease, standard, and all test groups (P<0.01, ns: non-significant). The disease group is compared with the normal, standard, and all treated groups (#P<0.05, ##P<0.01, ###P<0.001, ns: non-significant). The standard group is compared with all test groups (ns: non-significant).

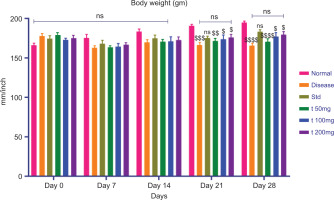

3.3.2. Change in Body Weight

Body weight of the study rats was recorded twice weekly. A significant reduction in body weight was observed in the CFA-treated (disease control) group. In contrast, animals in the standard treatment group (diclofenac) and the test formulation groups showed a significant increase in body weight compared to the disease control group. Figure 4 represents the data collected with statistical analysis.

All values are expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 8, using Two-Way Multiple Comparison. The normal group is compared with the disease, standard, and all test groups ($P<0.05, $$P<0.01, $$$P<0.001, $$$$P<0.0001, ns: non-significant). The disease group is compared with the normal, standard, and all treated groups (ns: non-significant). The standard group is compared with all test groups (ns: non-significant).

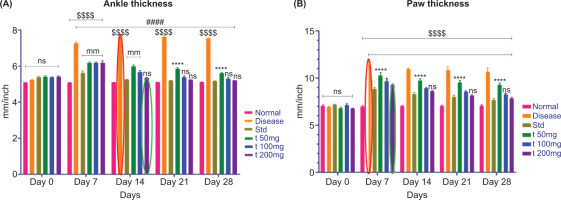

3.3. Ankle joint thickness and paw thickness

Ankle joint and paw thickness were assessed four times over the course of the study (day 0 baseline, day 7, day 21, and day 28) to evaluate progression and response to treatment in adjuvant-induced arthritis.

3.3.1. Ankle joint thickness

At baseline (day 0), the mean ankle joint thickness across all experimental groups (CFA-induced arthritis (disease control), standard treatment (diclofenac), and herbal formulation (200 mg)) was similar, and the mean ankle joint measurements confirmed that there was no pre-existing inflammation or swelling.

On day 7, the CFA-induced arthritis group showed significantly increased ankle joint thickness, confirming that an inflammatory response and joint swelling dominated the mean ankle joint measurements, indicative of rheumatoid arthritis onset. In contrast, the diclofenac and herbal formulation groups demonstrated significantly lower swelling at the ankle site, suggesting that the anti-inflammatory therapeutic effects were noticeable during the onset of treatment.

As treatment progressed beyond the seven-day time point (i.e., on day 21 and day 28), the mean ankle joint thickness values in both the standard and herbal treatment groups remained consistently and significantly lower than those of the disease control group, suggesting a continued and progressive reduction in inflammation for both experimental groups following treatment intervention. The herbal formulation demonstrated a therapeutic effect on mean ankle joint thickness similar to that of the diclofenac treatment group, as shown in Figure 5A, which illustrates the longitudinal temporal changes as well as the mean ankle thickness for each experimental group. Overall, the data presented here represent the anti-arthritic potential of the treatment groups in preserving joint structural integrity and reducing inflammation.

Figure 5

Effect of ArthoCan-V50 tablets on Ankle joint and Paw thickness in CFA induced RA in Wistar rats.

All values are expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 8, using Two-Way Multiple Comparison. For panel A, the normal group is compared with the disease, standard, and all test groups (P<0.0001, ns: non-significant). The disease group is compared with the normal, standard, and all treated groups (####P<0.0001, ns: non-significant). The standard group is compared with all test groups (****P<0.0001, ns: non-significant). For panel B, the normal group is compared with the disease, standard, and all test groups (P<0.0001, ns: non-significant). The disease group is compared with the normal, standard, and all treated groups (####P<0.0001, ns: non-significant). The standard group is compared with all test groups (*P<0.05, ****P<0.0001, ns: non-significant).

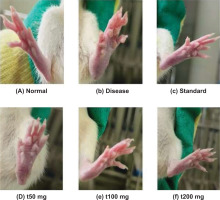

3.3.2. Paw measurements

In similar paw measurements of thickness, a comparable trend was observed (Figure 5B). On day 0, there were no statistically significant differences between the groups. By day 7, there was a notable increase in paw thickness in the CFA group, indicating that the joint was in an “acute” state of inflammation. However, both the diclofenac and ArthoCan-V50 treatment groups showed a significantly lesser increase in paw thickness, indicating early suppression of the inflamed state.

On days 21 and 28, both treatment groups showed a proportionate and significant decrease in paw thickness, indicating a continued anti-inflammatory action. These results suggest that the therapeutic component(s) in the herbal formulation can decrease paw edema and joint inflammation to the same degree as the classical anti-inflammatory agent, diclofenac.

Together, the measurements of paw and joint thickness provide quantifiable data indicating that the herbal treatment has anti-inflammatory activity in a rodent model of rheumatoid arthritis, as well as the potential for its use as a multimodal treatment approach.

A remarkable decrease in paw swelling and assessments of arthritis was observed after 28 days of treatment with ArthoCan V50 tablets compared to the disease control (CFA-induced) group, indicating that ArthoCan V50 has a significant therapeutic effect on reducing the inflammatory pathology associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Treatment with ArthoCan V50 not only improved visible indicators of inflammatory change but also produced additional beneficial clinical effects on the overall severity of arthritis. Figure 6 supports these observations, showing statistically significant decreases in paw thickness in animals treated with ArthoCan V50 compared to the untreated disease control group, further demonstrating the visible anti-inflammatory effects of this formulation in the preclinical model.

3.4. Serum analysis

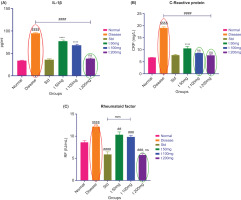

3.4.1 IL-1βlevels

Levels of IL-1β were significantly higher in the disease control group than in the untreated control group, indicating increased inflammatory activity. IL-1β levels were remarkably lower in the standard (diclofenac) treatment group compared to the disease group. IL-1β levels were also reduced in the ArthoCan-V50 treatment groups. The 200 mg (t200) dose significantly decreased IL-1β levels more than the 50 mg (t50) dose. The data indicate dose-dependent anti-inflammatory effects (Figure 7A).

3.4.2. TNF- α levels

Compared to the normal control group, TNF-α levels were significantly higher in the disease control group, indicating an ongoing active inflammatory response. The standard treatment group (diclofenac) showed a decrease in TNF-α levels compared to the disease control. TNF-α levels measured in the ArthoCan-V50 tablet treatment groups also showed a marked reduction from baseline values when compared to the disease control group, indicating the anti-inflammatory effects of the formulation. The 200 mg group (t200) notably had lower TNF-α levels than the 50 mg group (t50), demonstrating a greater reduction in TNF-α in favour of the higher dose group.

All values are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 8) and analysed using one-way ANOVA followed by multiple comparison tests. For panel A, the normal group is compared with the disease control group (P < 0.0001). The disease control group is compared with the normal, standard, and treated groups (####P < 0.0001). The standard group is compared with the test groups (*P < 0.05, ****P < 0.0001). For panel B, the normal group is compared with the disease control group (P < 0.0001). The disease group is compared with the normal, standard, and all treated groups (####P < 0.0001). The standard group is compared with all test groups (****P < 0.0001, ns: non-significant). For panel C, the normal group is compared with the disease control group (P < 0.0001). The disease group is compared with the normal, standard, and all treated groups (##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001, ####P < 0.0001). The standard group is compared with all test groups (****P < 0.0001, ns: non-significant). For panel D, the normal group is compared with the disease and standard groups (P < 0.0001, ns: non-significant). The disease group is compared with the normal, standard, and all treated groups (#P < 0.05, ###P < 0.001, ####P < 0.0001, ns: non-significant). The standard group is compared with all test groups (*P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001, ns: non-significant).

3.4.3 C-reactive protein (CRP) (ng/ml)

C-reactive protein (CRP) values (ng/mL) in the normal group were significantly lower than in the disease control group, reflecting the absence of systemic inflammatory activity. As anticipated, CRP values were markedly increased in the CFA-induced disease group, which exhibited active inflammation. However, treatment with the ArthoCan-V50 tablets resulted in a remarkably lower CRP score compared to the disease group. Furthermore, a greater decrease was observed in the 200 mg dose of ArthoCan-V50 compared to the 50 mg group (Figure 7B).

3.4.4. Rheumatoid factor RF (IU/mL)

Likewise, rheumatoid factor (RF) values (IU/mL) were significantly higher in the disease group compared to the normal group, confirming the autoimmune condition of the induced arthritis. Treatment with ArthoCan-V50 had a significant effect on decreasing RF levels, with the 200 mg dose again showing a greater outcome compared to the 50 mg dose (Figure 7C), reaffirming the immunomodulatory potential of the herbal formulation.

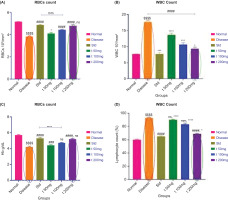

3.5. Complete blood count (CBC)

The disease group exhibited a decrease in red blood cell (RBC) count and hemoglobin levels compared to the normal group, while white blood cell (WBC) and lymphocyte counts were elevated (Figure 8). Similarly, RBC and hemoglobin levels were significantly lower in the disease group than in both the standard and treatment groups, whereas WBC and lymphocyte counts were higher. Treatment with ArthoCan-V50 tablets led to a marked improvement, showing increased RBC and hemoglobin levels and reduced WBC and lymphocyte counts relative to the disease group. Furthermore, the 200 mg treatment group demonstrated a greater increase in RBC and hemoglobin levels and a more pronounced decrease in WBC and lymphocyte counts compared to the 50 mg treatment group.

Figure 8

Effect of ArthoCan-V50 tablets on the level of RBCs, WBCs, Haemoglobin and Lymphocyte count in CFA induced RA in Wistar rats.

All values are expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 8, using One-Way Multiple Comparison. The normal group is compared with the disease and standard groups ($$$$P<0.0001, ns: non-significant). The disease group is compared with the normal, standard, and all treated groups (#P<0.05, ###P<0.001, ####P<0.0001, ns: non-significant). The standard group is compared with all test groups (*P<0.05, ***P<0.001,****P<0.0001, ns: non-significant).

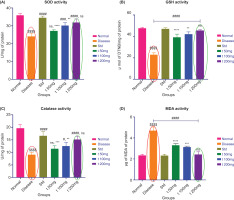

3.6. Antioxidant parameters

3.6.1 Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity

Figure 9A shows that rats in the CFA-induced arthritis (disease) group had significantly lower superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity than the normal control group, supporting increased oxidative stress due to inflammation. SOD is a physiological antioxidant enzyme involved in neutralizing superoxide radicals; therefore, reduced SOD activity indicates diminished cellular defense. Treatment with ArthoCan-V50, particularly at the 200 mg dosage, resulted in a beneficial outcome, with SOD activity recovering—potentially approaching normal levels—suggesting that the formulation has strong potential to reinstate oxidative balance and mitigate impairment associated with inflammatory oxidative stress.

3.6.2. Reduced glutathione (GSH) levels

Glutathione (GSH) is a non-enzymatic antioxidant essential for detoxification and maintaining redox homeostasis. As shown in Figure 9B, baseline GSH levels were significantly lower in the disease group compared to the normal control, indicating the presence of oxidative stress and a reduction in antioxidant activity. Furthermore, treatment with ArthoCan-V50 resulted in a near restoration of GSH levels in a dose-dependent manner. Re-synthesis of GSH was significantly higher in both the 100 mg and 200 mg groups, indicating that the formulation improved cellular defense capacity against oxidative injury and exhibits potential regenerative properties.

All values are expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 8, using One-Way Multiple Comparison. For panel A, the normal group is compared with the disease control group (P<0.0001). The disease group is compared with the normal, standard, and all treated groups (###P<0.001, ####P<0.0001, ns: non-significant). The standard group is compared with all test groups (**P<0.01, ****P<0.0001, ns: non-significant). For panel B, the normal group is compared with the disease control group (P<0.0001). The disease group is compared with the normal, standard, and all treated groups (###P<0.001, ####P<0.0001, ns: non-significant). The standard group is compared with all test groups (**P<0.01, ****P<0.0001, ns: non-significant). For panel C, the normal group is compared with the disease control group (P<0.0001). The disease group is compared with the normal, standard, and all treated groups (#P<0.05, ####P<0.0001, ns: non-significant). The standard group is compared with all test groups (**P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001, ns: non-significant). For panel D, the normal group is compared with the disease control group (P<0.0001). The disease group is compared with the normal, standard, and all treated groups (#P<0.05, ####P<0.0001, ns: non-significant). The standard group is compared with all test groups (**P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001, ns: non-significant).

3.6.3. Catalase (CAT)

Catalase (CAT) activity (Figure 9C) was significantly reduced in the disease group, likely due to enzyme inactivation caused by oxidative stress. Catalase helps protect tissues from oxidative damage by catalyzing the conversion of hydrogen peroxide to water and oxygen. Both the standard treatment (diclofenac) and ArthoCan-V50 at 200 mg significantly increased CAT levels, indicating restoration of oxidative balance, along with partial recovery of enzymatic antioxidant activity (EAA).

3.6.4 Lipid peroxidation (MDA) activity

Lipid peroxidation, with malondialdehyde (MDA) as a marker of oxidative damage to the cell membrane, was measured. Figure 9D indicated significantly elevated levels of MDA in the CFA-induced disease group, demonstrating increased lipid peroxidation due to chronic inflammation. Both the standard treatment and ArthoCan-V50 (especially at 200 mg) significantly decreased MDA levels and showed a protective role against membrane lipid damage. The reduction in lipid peroxidation is an important step in understanding the ability of ArthoCan-V50 to reduce oxidative damage and support cellular restoration following inflammation.

3.7. Histopathological study & imagej analysis

Histopathological examination of the ankle joint sections revealed evidence of tissue changes that adhered to the bone in relation to disease progression and therapeutic intervention. The CFA-treated disease control groups displayed extensive joint inflammation with synovial membrane hyperplasia, marked infiltration of inflammatory cells, surface irregularities in the cartilage, abundant swelling, and deformity of the distal element architecture. These changes are representative of chronic active inflammation and subsequent tissue degeneration, which are characteristic features of the pathophysiology of rheumatoid arthritis.

In contrast, the animals treated with the herbal formulation ArthoCan-V50 at all dose levels (50, 100, and 200 mg) displayed significantly preserved joint architecture. The histological sections from these groups showed mild surface damage, no collagen destruction, healthy chondrocyte distributions, and little to no leakage of inflammatory cells through the synovium, while the reactive zone demonstrated intact chondrocytes and preserved calcium and collagen. There were no signs of osteoclastic activity or erosion of subchondral bone, suggesting a protective effect of this treatment against inflammatory bone resorption.

For quantitative analysis, ImageJ software was utilized to complement the histological descriptive values of the tissue changes. Using the pixel density and cell segmentation algorithm functions, quantification of viable cell counts was obtained. As indicated in Figure 10, there were fewer viable cells in the CFA disease control group, consistent with the observable histological damage. In contrast, all groups treated with ArthoCan-V50 exhibited significant increases in viable cell density when calculated as combined groups, with the highest cell density corresponding to the 200 mg treatment group, demonstrating the benefits of preserving joint integrity and reducing cell death.

Similarly, while CFA-treated joints had a significant number of resorption pits and osteoclasts present in the subchondral bone—signs associated with bone degradation—the treatment groups showed little to no evidence of such changes or exhibited significant reductions in the number of resorption pits and osteoclasts, demonstrating effective extracellular chondroprotective and anti-resorptive effects. Overall, these results demonstrate the anti-inflammatory and joint-protective efficacy of ArthoCan-V50 using the CFA-induced arthritis model.

4. DISCUSSION

RA is a chronic autoimmune disorder affecting about 1% of the global population, and is typically marked by synovial inflammation, joint swelling, deformity, and functional impairment (Cameron et al., 2011). The findings of the ArthoCan-V50 study provide strong evidence supporting the potential future use of the formulation as a nutraceutical for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA). The overall analysis of the formulation’s effects on CFA-induced arthritis in Wistar rats, coupled with the known safety and effectiveness of the product, aligns with the growing interest in natural therapies for autoimmune diseases. Several aspects merit further investigation to reinforce and expand upon this study, including the mechanistic effects of the constituent herbs on anti-arthritic activity, immune modulation, and the time course of the formulation’s effects on cytokine levels and oxidative stress.

ArthoCan-V50 consists of six parent herbs, all of which have long histories of being known to exert anti-arthritic effects through various mechanisms. The parent herbs of ArthoCan-V50—Boswellia serrata, Vitex negundo, Zingiber officinale, Ricinus communis, Curcuma longa, and Cannabis sativa—have been comprehensively researched for their pharmacological relevance to RA. Although each parent herb may be effective as an anti-arthritic agent on its own, the true value of ArthoCan-V50 lies in the combination of these herbs and their synergistic activity, which contributes to a greater overall efficacy of the formulation.

Boswellia serrata, a herb known to modulate the 5-lipoxygenase pathway—an important pathway in the formation of pro-inflammatory leukotrienes (Du et al., 2015)—has been shown to significantly reduce pain and inflammation associated with RA by regulating leukotriene synthesis and subsequently decreasing activation of inflammatory pathways (Kumar et al., 2019). It is noteworthy that Boswellia serrata is more selective for 5-lipoxygenase than non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), which typically induce higher levels of systemic side effects (Siddiqui, 2011). Vitex negundo, with its known anti-inflammatory and anti-osteoporotic properties, has shown promise in reducing RA-related bone loss (Zheng, Zhao, et al., 2014). Vitex negundo downregulates pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β and TNF-α, which are responsible for bone resorption and cartilage degradation (Zheng, Zhang, et al., 2014).

The active component in ginger (Zingiber officinale), gingerol, has been well established as an analgesic and anti-inflammatory agent (Van Breemen et al., 2011). Various studies have demonstrated that ginger inhibits the production of prostaglandins and suppresses the enzymes COX-1 and COX-2 through its anti-inflammatory and pain-reducing effects (Al-Nahain et al., 2014). Therefore, ginger provides a dual function in addressing inflammatory conditions by inhibiting both inflammation and pain. The seeds of Ricinus communis possess pharmacological properties, with various studies establishing their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory capabilities (Hussain et al., 2021). In rheumatoid arthritis (RA), oxidative stress plays a significant role in disease progression. As a free radical scavenger, Ricinus communis may mitigate oxidative stress (Gupta et al., 2023).

While the active component in turmeric, curcumin, is a well-known anti-inflammatory agent and exhibits broad-spectrum antioxidant and immunomodulatory effects, curcumin inhibits activation of NF-kB (nuclear factor kappa B), a transcription factor involved in inflammation and immune response (Bagherniya et al., 2021; Kou et al., 2023; Menon & Sudheer, 2007). Curcumin was likely added to this formulation to decrease pro-inflammatory cytokines and oxidative stress. The therapeutic use of Cannabis sativa for pain and inflammation management is well established. The primary cannabinoids in cannabis, delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD), interact with our endocannabinoid system, which is involved in the regulation of inflammation and immune functioning (Boggs et al., 2016; Capodice & Kaplan, 2021). This established profile of cannabis makes it an attractive candidate in the formulation because of its potential to manage pain and inflammation alongside the presumptive action of the other herbs (Leinen et al., 2023). The OECD 423 acute oral toxicity study demonstrated that ArthoCan-V50 is safe for consumption at doses of up to 2000 mg/kg, which suggests that it may be suitable for long-term use in managing chronic conditions like RA (Zhao et al., 2022). This finding aligns with other studies on the individual herbs, which have shown favorable safety profiles in both acute and chronic dosing regimens (Prajapati & Doshi, 2025).

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) pathogenesis is a result of dysregulated immune responses with an abundance of pro-inflammatory cytokines, e.g., TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 (Kondo et al., 2021). These pro-inflammatory cytokines are critical mediators involved in the activation of immune cells, synovial hyperplasia, injury to cartilage, and bone erosion in patients with RA. In this study, treatment with ArthoCan-V50 was found to reduce the levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, suggesting immunomodulatory behavior of ArthoCan-V50.

Oxidative stress is an important characteristic of RA that contributes to joint damage. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and lipid peroxidation generated from oxidative stress ultimately cause cellular damage and the activation of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), which are responsible for breaking down the extracellular matrix (Ding et al., 2023; Mukherjee & Das, 2024). This leads to progressive joint destruction. ArthoCan-V50 played important roles in restoring antioxidant enzyme levels (e.g. SOD, CAT, and GSH) to help overcome oxidative stress and minimize further joint damage (Fernandes et al., 2002). The ability of the formulation to promote the restoration of these antioxidant enzymes aligns with its proposed role in minimizing the long-term oxidative damage associated with RA (Li et al., 2018; Quiñonez-Flores et al., 2016). Curcumin has been found to inhibit the expression of TNF-α and IL-1β in animal studies on arthritis (Zhang et al., 2016), and Boswellia serrata was found to reduce IL-6 in RA patients (Ammon, 2016). The overall role of these herbal components in lowering inflammatory cytokine expression makes a very important contribution to the anti-arthritic effects of the formulation.

Curcumin and ginger show positive antioxidant effects documented in the literature. Curcumin has demonstrated antioxidant capability by scavenging ROS and increasing the expression of endogenous antioxidants such as SOD and CAT (Sathyabhama et al., 2022). Likewise, ginger has been shown to protect the body against oxidative stress by enhancing antioxidant enzyme activity (Ayustaningwarno et al., 2024). The combined effect of these antioxidants in ArthoCan-V50 has likely contributed to the decrease in oxidative damage observed in the RA model.

The histopathological study also supports the anti-arthritic properties of ArthoCan-V50. The observed decrease in synovial inflammation and preserved cartilage integrity in treated animals are directly correlated with the anti-inflammatory and chondroprotective effects of the formulation. The increase in chondrocyte viability also indicates its potential in protecting against cartilage degeneration, which is one of the goals of RA treatment.

Hematological changes in RA models typically demonstrate signs of anemia of chronic inflammation and increased white blood cell counts. The reversal of these hematological changes by ArthoCan-V50 is indicative of the formulation’s immunomodulatory and hematological effects, which were likely due to the cumulative influence of the phytochemicals on immunological and inflammatory pathways.

The preclinical evidence presented above indicates that ArthoCan-V50 has potential anti-inflammatory properties, including the ability to reduce joint inflammation, and may therefore be a suitable candidate for clinical research in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). More specifically, its capacity to decrease joint damage and systemic inflammation suggests potential usefulness as an adjunct or even complementary therapy for patients seeking plant-based “traditional” medicine with an acceptable safety profile.

It should be emphasized that this study is limited by the use of an animal model. Although the CFA-induced arthritis model demonstrates some efficacy in replicating human RA—particularly in terms of inflammatory joint involvement and bone erosion—it does not fully capture the complex immunopathogenesis or chronic nature of the disease in humans. Differences in immunological responses and metabolic pathways, including drug absorption, may lead to variations in translational outcomes between rodents and humans.

Nonetheless, the data provide valid justification to ultimately conduct Phase I clinical trials for ArthoCan-V50 to evaluate development feasibility, safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics in humans. If safety is established in the Phase I trial, subsequent clinical studies would assess the efficacy of the formulation when used with or without conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) therapy. Conducting such trials could bridge the gap between experimental research and evidence-based clinical practice for patients with RA.

5. CONCLUSION

We have demonstrated that ArthoCan-V50 is safe at high doses and is potentially clinically relevant for the treatment of CFA-induced arthritis in rats. The formulation reduced inflammatory markers (TNF-α, IL-1β, CRP, RF), elevated antioxidant enzymes (SOD, GSH, CAT), and offered some protection from joint damage. We speculate that the effects of ArthoCan-V50 are due to the synergistic action of the various herbal components, whose individual anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities have been separately established in the literature. While the CFA animal model reflects some aspects of RA, it does not represent the complete nature of the human disease, nor does it account for immunological and metabolic differences that may limit translational efficacy. That said, our data provide a reasonable rationale to move forward to Phase I trials of ArthoCan-V50 to assess safety and feasibility in efficacy trials, either in combination with or without additional DMARDs. In conclusion, we believe that ArthoCan-V50 has the potential to be a valuable modality in the adjuvant therapy for rheumatoid arthritis.