1. INTRODUCTION

Hyperpigmentation, or the darkening of skin color due to sun exposure and other factors, remains a major aesthetic concern that can negatively impact an individual’s quality of life (Jusuf et al., 2019; Platsidaki et al., 2023; Yalamanchili et al., 2015; Zhu et al., 2022). Currently, people often use agents such as hydroquinone to treat hyperpigmentation, but these agents are becoming more and more linked to different side effects (Gonzaga da Cunha & Paula da Silva Urzedo, 2023; Maddaleno et al., 2021; Piętowska et al., 2022). Therefore, we need a safer way to stop hyperpigmentation.

A recent study has shown that eating foods high in carotenoids may help stop hyperpigmentation (Hashemi-Shahri et al., 2017; D. H. Lee et al., 2018a; Phacharapiyangkul et al., 2021). Carotenoids benefit the skin by inhibiting melanogenesis through different signaling pathways, including the protein kinase A (PKA), extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), and protein kinase B (AKT) pathways. Through those pathways, carotenoids decreased the tyrosinase and MITF expression (Fiedor & Burda, 2014; Rivera-Madrid et al., 2020; Saini et al., 2022).

Red fruit (Pandanus conoideus Lam.) is a traditional fruit from the highlands of Papua that is known to have a lot of antioxidants. Carotenoids are very high in red fruit oil (RFO), which comes from this fruit. There have been about 1580 publications about P. conoideus Lam in the last 10 years, according to Google Scholar. However, there are not many studies that look at its possible benefits for skin health. Over the past 10 years, only two articles were found that looked at how red fruit affects skin health. Most of the research that has been done on red fruit has focused on its ability to fight cancer, inflammation, and free radicals (Astuti et al., 2007; Wayan Sugiritama, n.d.; Heriyanto et al., 2021; Ratnawati et al., 2023). In a study with UVB-irradiated mice, Sugianto et al. (2019) showed that RFO, which has β-carotene and tocopherol in it, could lower the expression of the MMP-1 gene (Sugianto et al., 2019). Dumaria et al. (2018) revealed that 10% red fruit cream showed an antimelanogenic effect and could inhibit melanin in Cavia porcellus, which had been exposed to UVB exposure. The effect was as effective as 4% hydroquinone cream (Dumaria et al., 2018). These results suggest that RFO may inhibit melanogenesis, similar to the mechanism observed in other carotenoid-rich plants that suppress pigmentation.

So far, limited studies have examined the effects of red fruit on melanogenesis using cell culture models. This study aims to fill that gap by investigating the effect of RFO on MITF gene expression and its potential to inhibit melanogenesis in B16F10 melanoma cells. This study uses α-MSH to induce melanogenesis in cell culture, mimicking the effects of UV radiation. Arbutin is used as a positive control for tyrosinase inhibition.

2. METHODS

2.1. Sample preparation

RFO, the primary test sample, was obtained from PT. Prima Solusi Medikal (Jakarta, Indonesia). Alpha arbutin (batch no. AT01230710), used as a positive control, was sourced from PT Kaizen and manufactured by Shandong Topscience Biotech Co., Ltd. Melanocyte-stimulating hormone (α-MSH, Sigma-Aldrich, M4135) was used to induce melanogenesis.

2.2. Phytochemical screening of RFO

A preliminary phytochemical screening was conducted to detect secondary metabolites in RFO, including phenolics, tannins, flavonoids, saponins, triterpenoids, steroids, and alkaloids. To test for phenolic compounds, a 5% ferric chloride (FeCl3) reagent was added to the sample, and the color changes were watched. A 1% FeCl3 solution was used to look at tannins in the same way as the sample (Maheshwaran et al., 2024).

There were three different reagents used to find flavonoids: (1) the Shinoda test, which used magnesium ribbon and then concentrated hydrochloric acid (HCl); (2) the addition of 2N sulfuric acid (H2SO4); and (3) treatment with 10% sodium hydroxide (NaOH). Each method relied on color changes to confirm the results. Saponins were assessed using the foam test, in which the sample was diluted with water, gently heated, and vigorously shaken to observe froth formation (Maheshwaran et al., 2024).

We used the Liebermann–Burchard reaction to look at triterpenoids and steroids. We mixed the sample with concentrated sulfuric acid and glacial acetic acid to make a certain color reaction. Alkaloids were detected using Dragendorff’s reagent, which reacts with alkaloid compounds to form a colored precipitate (Maheshwaran et al., 2024).

2.3. Detection of β-carotene using thin-layer chromatography

The system eluent for the flash chromatography column was first determined through thin-layer chromatography (TLC). Trial and the eluent system for flash column chromatography was first determined using TLC through a trial-and-error approach. The chemical N-he and the ethyl acetate compound were chosen as the mobile phase, and their polarity was adjusted by varying the volume ratios to obtain the optimal separation. After applying the RFO samples onto the TLC plates, several solvent systems with different n-hexane to ethyl acetate ratios (v/v) were tested, including 100% n-hexane, 100% ethyl acetate, and various combinations of both solvents.

Once the optimal solvent system was identified, 1 g of the RFO sample was loaded into a chromatography column, and elution was performed using the selected eluent. The eluate was collected in 54 vials, with each vial containing 2–3 mL of eluate. The contents of each vial were analyzed by TLC to observe the separation profile. Fractions showing the same Rf values were pooled together for further analysis.

2.4. Cell culture of the murine melanoma B16-F10 cells

The protocol outlined by Zhou et al. (2021a) was followed to culture B16-F10 murine melanoma cells (ATCC® CRL-6475™) in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 medium (Gibco, 11875-093), enriched using 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco, 10270-106) along with 1% antibiotic–antimycotic solution (Sigma-Aldrich, P4333). The cells were incubated in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 at 37 °C.

2.5. Cell viability assessment using the resazurin assay

B16-F10 cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 17,000 cells/well and incubated at 37 °C in a humidified environment with 5% CO2 until approximately 70% confluency was attained. Subsequent to 24 hours, the cells were administered varying amounts of RFO and then cultured for an additional 48 hours under identical conditions.

After treatment, the culture media in every single well were extracted. A functional solution was formulated by combining 1 mL of Resazurin Sodium Salt (BioReagent, Sigma-Aldrich, R7017) with 9 mL of RPMI medium (final concentration: 10 µL reagent per 90 µL media). Subsequently, 100 µL of this combination was dispensed into each well, and the plates were incubated for 1–2 hours at 37 °C. A multimode microplate reader was used to detect absorbance at 570 nm, and color variations were visually observed.

2.6. Melanogenesis induction

Melanogenesis was induced in B16F10 melanoma cells by treatment with 100 nM α-MSH (Sigma-Aldrich, M4135) for up to 48 hours. Cells were simultaneously exposed to α-MSH and test compounds in 24-well plates, and samples were collected at 24 and 48-hour time points.

2.7. Treatment groups and sample collection

Following α-MSH induction, cells were treated with various concentrations of RFO (12.5, 25, 50, and 100 µg/mL) for an additional 24 or 48 hours. A positive control group received 633.5 µg/mL alpha-arbutin, while a negative control group received medium without any treatment. After incubation, cells were harvested and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 5 minutes at 4 °C. Cell pellets were visually assessed, imaged, and processed for downstream RNA extraction and gene expression analysis.

2.8. RNA extraction and qPCR

Total RNA was isolated from B16-F10 cells following 48 hours of treatment with the GENEzol™ Reagent (Geneaid, GZR200), following the manufacturer’s guidelines. Reverse transcription and amplification of target genes were executed utilizing the SensiFAST™ SYBR® No-ROX One-Step Kit (Bioline, BIO-72005), and real-time PCR (qPCR) was carried out with the Agilent AriaMX Real-Time PCR System, adhering to the kit protocol.

The specific primers used for the quantitative analysis were as follows:

for GAPDH, the forward primer was 5'-GCAGCGAACTTTATTGATGGTATT-3' and the reverse primer was 5'-CACTGAGCAAGAGAGGCCCTAT-3'; for MITF, the forward primer was 5'-AGAAGCTGGAGCATGCGAACC-3' and the reverse primer was 5'-GTTCCTGGCTGCAGTTCTCAAG-3'.

MITF expression was normalized to GAPDH and expressed as a fold change relative to the untreated control group. Relative expression was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method.

2.9. Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism version 10.00 for Windows (GraphPad Software, LLC, San Diego, CA, USA). Data normality and homogeneity were assessed to determine whether a parametric or nonparametric test should be applied. Parametric tests were applied when both assumptions were satisfied, and nonparametric tests were used otherwise.

3. RESULTS

This laboratory-based experimental study was conducted at the Central Laboratory of Universitas Padjadjaran. The research utilized B16F10 melanoma cell cultures stimulated with α-MSH. Samples were obtained from confluent and uncontaminated cultured cells. The study included seven groups: one media control (medium + cell) group, one negative control group, and one positive control group, and four treatment groups. The treatment groups consisted of B16F10 cells that were stimulated with α-MSH and given RFO at concentrations of 12.5, 25, 50, and 100 μg/mL, respectively. The media control group contained untreated B16F10 cells, and the negative control group included cells that were only stimulated with α-MSH. Cells that were treated with Arbutin and α-MSH made up the positive control group.

3.1. The result of phytochemical screening of RFO

Phytochemical screening of RFO revealed the presence of several bioactive compounds. As shown in Table 1, a positive reaction with 5% ferric chloride indicated the presence of phenolic compounds, while no blue-black precipitate was observed with 1% ferric chloride, suggesting the absence of tannins. The sample tested negative for flavonoids, as no color changes were observed in the Shinoda, 2N H2SO4, or 10% NaOH tests.

Table 1

Results of phytochemical screening of RFO.

Saponins were detected through the formation of persistent froth after vigorous shaking and gentle heating, consistent with their surfactant properties. The Liebermann–Burchard test produced a distinct violet ring at the interface, indicating a strong presence (+++) of triterpenoids and/or steroids. Meanwhile, no precipitate was observed upon the addition of Dragendorff’s reagent, suggesting the absence of alkaloids. These findings confirm that RFO contains multiple bioactive compounds, particularly triterpenoids, steroids, saponins, and phenolics, which may contribute to its biological activity.

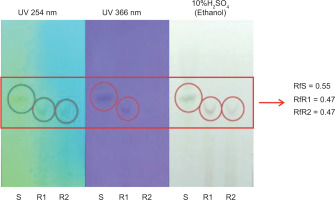

3.2. Detection of β-carotene by TLC

TLC was used to analyze the presence of β-carotene in RFO fractions before and after heating. Various solvent systems of n-hexane and ethyl acetate were tested, and the optimal separation was achieved using a specific ratio determined by trial and error. The RFO samples showed spots with Rf values of 0.55 before heating and 0.47 after heating, as shown in Figure 1, which were comparable to the β-carotene standard. Observations under visible light, UV 254 nm, and UV 366 nm confirmed the presence of compounds with similar migration and fluorescence characteristics, suggesting the retention of β-carotene or its derivatives in the samples.

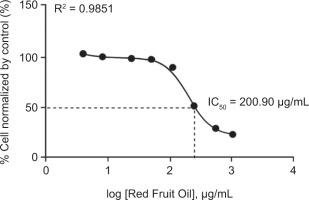

3.3. Cytotoxicity evaluation of RFO on B16-F10 melanoma cells

The cytotoxic activity of RFO was evaluated using B16-F10 melanoma cells through the Resazurin assay. As shown in Figure 2, the IC50 value obtained was 200.90 µg/mL, indicating a moderate level of cytotoxic activity. In addition, results from the Resazurin assay showed that higher doses of RFO induced morphological changes in the cells, such as increased cell size, which may be associated with cytotoxic effects. Signs of cytotoxicity, including cell shrinkage, detachment, and rounding, were observed, suggesting membrane and structural damage to melanoma cells. However, RFO did not exhibit toxic effects on B16-F10 cells at concentrations of 125, 62.5, 31.25, 15.63, and 7.81 µg/mL, indicating that it is safe at lower concentrations.

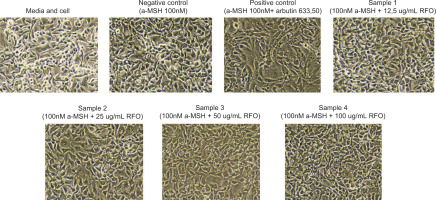

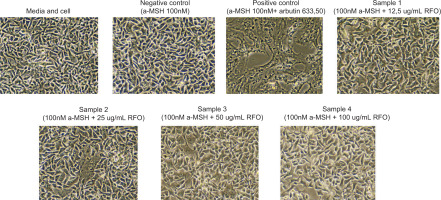

3.4. Visual observation and morphological workflow of treated B16F10 cells

Throughout the experimental workflow, B16F10 melanoma cells were seeded into 24-well plates and incubated with 100 nM α-MSH to induce melanogenesis. Cells were then treated with RFO at concentrations of 12.5, 25, 50, and 100 µg/mL, while a combination of α-MSH and 633.5 µg/mL arbutin served as the positive control. The incubation periods were set at 24 and 48 hours before RNA extraction for qPCR analysis.

During the collection process, a visible darkening of the cell pellets was observed in α-MSH-treated groups, in contrast to the lighter-colored pellets in the untreated media control. This darkening is consistent with increased melanin content, qualitatively supporting successful induction of melanogenesis.

Although no photographic documentation was captured at the time of cell harvesting, a schematic workflow illustrating sample groupings and treatment timelines is provided in Figures 3 and 4 to support transparency of the experimental design and sampling protocol.

3.5. The effect of RFO at various concentrations in cultured cells on MITF gene expression

To assess the effect of RFO on gene expression associated with melanogenesis, cells were treated with various concentrations of RFO and incubated for 24 and 48 hours. A more pronounced and consistent decrease in gene expression was observed after 48 hours of incubation. MITF expression was quantitatively assessed using the real-time PCR technique. Data were analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCt method with GADPH as the internal control. Expression values were normalized to the untreated media control (medium + cell) group. This analysis allowed for comparison of MITF expression between groups treated with α-MSH alone, α-MSH + arbutin (positive control), and α-MSH combined with increasing concentrations of RFO.

Figure 5 presents a comparison of MITF gene expression ratios across seven experimental groups. The media control group showed an average MITF ratio of 1.04 ± 0.20, the negative control group 0.85 ± 0.08, and the positive control group 0.57 ± 0.03. The first treatment group had an average of 0.96 ± 0.08, the second treatment group 0.65 ± 0.09, the third treatment group 0.96 ± 0.02, and the fourth treatment group showed a notably higher average of 3.40 ± 1.42.

A Shapiro–Wilk test was conducted to determine normality, and Levene’s test was executed to determine homogeneity, following the descriptive analysis of MITF gene expression. The Shapiro–Wilk test’s results indicated that the data were normally distributed, as all groups had p-values > 0.05, but the homogeneity test showed a significant p-value (p < 0.05). Consequently, a Kruskal–Wallis nonparametric test was conducted, resulting in a p-value of 0.1117, which suggests that there is no statistically significant difference between the categories (p > 0.05). Post hoc analysis that utilized the Mann–Whitney test was not implemented due to the absence of significance in the Kruskal–Wallis test.

4. DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to determine whether RFO can modulate MITF gene expression as part of its antimelanogenic potential in α-MSH-stimulated B16F10 melanoma cells. Although the reduction in MITF expression was not statistically significant, a dose-dependent decreasing trend was observed at 12.5–50 µg/mL. Interestingly, 100 µg/mL of RFO produced an upsurge in MITF expression, indicating a potential biphasic or hormetic response (Calabrese and Mattson, 2017). Though the reduction of MITF by RFO (~2-fold at 50 μg/mL) was modest, it resembled the effect of arbutin, a known depigmenting agent that primarily inhibits tyrosinase activity rather than transcription (Bhalla et al., 2023). This suggests that RFO may also exert post-transcriptional or enzymatic regulatory effects. Prior studies on P. conoideus indicate its oil can modulate melanogenesis via tyrosinase degradation through the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway (Mayuko et al., 2018), providing a plausible mechanism beyond gene suppression.

The rebound in MITF expression at 100 μg/mL RFO could stem from pro-oxidant effects of carotenoids at high concentrations. High-dose β-carotene has been observed to induce oxidative stress in cell culture, reversing its protective effects (Rivera-Madrid et al., 2020; Saini et al., 2022). Stress signals like MAPK and NF-κB, when activated, can paradoxically promote MITF expression as part of a cellular stress response (Kim et al., 2013; J. Y. Lee et al., 2019). Hormesis, a phenomenon where low doses of a compound exhibit beneficial effects while higher doses trigger the opposite—has been observed with various phytochemicals and dietary antioxidants (Calabrese and Mattson, 2017). Our results suggest that RFO contains bioactive constituents with an optimal dose range for antimelanogenic activity.

The decreasing trend in MITF at moderate RFO doses aligns with reported antimelanogenic effects of carotenoids. Compounds like β-carotene may inhibit melanogenesis by reducing oxidative stress and influencing redox-sensitive signaling pathways (Wertz et al., 2005). Activation of melanocytes by α-MSH involves cAMP–CREB–MITF signaling, which can be downregulated by antioxidants that stabilize redox homeostasis (D’agostino & Diano, 2010; Wan et al., 2011). RFO’s high β-carotene content may enhance intracellular antioxidant activity, thereby suppressing melanogenic transcription factors. Similar effects were reported for banana peel extract, where carotenoid components significantly reduced MITF and tyrosinase in α-MSH-treated melanoma cells (Phacharapiyangkul et al., 2021). Furthermore, lutein and zeaxanthin, dietary carotenoids, have been shown to brighten skin tone and enhance antioxidant defenses in clinical studies (Juturu et al., 2016; Madaan et al., 2017; Roberts et al., 2009). While this study qualitatively identified the presence of β-carotene in RFO using TLC analysis, quantitative assays of antioxidant activity (e.g., DPPH, ABTS) were not conducted due to laboratory resource limitations. Nonetheless, the detection of β-carotene as a well-known antioxidant compound supports the hypothesis that RFO possesses bioactive potential. These findings highlight the need for further quantitative assays and mechanistic studies to elucidate the dual antioxidant–prooxidant role of RFO under varying concentrations.

Another possible explanation for the rebound in MITF expression at high RFO concentrations is reduced bioavailability due to aggregation of lipophilic carotenoids in cell membranes, which can limit their intracellular effectiveness (Yabuzaki, 2017). Future experiments should include ROS assays, tyrosinase activity, and melanin quantification to validate these hypotheses. Although the observed MITF reduction was not statistically significant, its biological relevance remains noteworthy. At moderate concentrations, the MITF-lowering effect of RFO was comparable to that of arbutin, a clinically recognized depigmenting agent. Considering MITF’s upstream role, even moderate reductions could translate into downstream suppression of melanin production over time.

An additional advantage of RFO lies in its phytochemical complexity. Unlike single-compound agents such as arbutin or hydroquinone, which can cause skin irritation or rebound hyperpigmentation, RFO contains a blend of carotenoids, tocopherols, and flavonoids (Dumaria et al., 2018; Mayuko et al., 2018; Sugianto et al., 2019). This kind of broad-spectrum action might be best for long-term conditions like melasma, where oxidative stress and inflammation are major causes. People are becoming more interested in nutricosmetics (Mayuko et al., 2018), and RFO has the potential to be both a topical and nutritional depigmenting agent. Recent studies have shown that foods high in carotenoids can help skin look better by blocking melanogenic signaling proteins like PKA, ERK, and AKT(Calniquer et al., 2021; Fiedor & Burda, 2014; Imokawa, 2019; Meléndez-Martínez et al., 2019; Zhou et al., 2021b). Our results support this possibility by showing that RFO works by suppressing MITF.

One limitation of this study is that the α-MSH treatment used (100 nM) did not increase MITF expression compared with untreated cells, which may be due to high basal MITF levels in unstimulated B16F10 cells, a plateau in α-MSH responsiveness, or differences in incubation time. This may limit the interpretation of RFO’s effects on MITF expression. In future experiments, we plan to perform a comprehensive dose–response and time–course analysis for α-MSH to ensure robust MITF induction. Further studies are also essential to elucidate the comprehensive antimelanogenic mechanism of RFO. Future research should focus on evaluating the impact of RFO on key melanogenesis-related enzymes such as tyrosinase, TRP-1, and TRP-2, as well as quantifying melanin content to confirm functional outcomes. In addition, research is necessary to ascertain the proximal regulatory effects of cellular signaling pathways, such as cAMP/PKA, MAPK, and PI3K/AKT. Investigating the antioxidant potential, bioavailability, metabolic fate, and pharmacokinetics of RFO components will provide insights into their therapeutic potential and safety. Long-term in vivo assessments and clinical trials are also needed to establish efficacy, optimal dosing, and possible adverse effects in humans. All of these studies will help RFO grow logically as a scientifically proven, safe, and effective plant-based treatment for hyperpigmentation.

5. CONCLUSION

In B16F10 melanoma cells stimulated with α-MSH, RFO from P. conoideus, which is high in β-carotene and other antioxidants, shows a dose-dependent modulatory effect on MITF, a crucial regulator in melanogenesis. RFO may have antimelanogenic effects by lowering MITF mRNA expression at low to moderate concentrations. This trend is comparable to that of established depigmenting agents such as arbutin and may involve antioxidant-mediated interference with α-MSH-induced signaling. In contrast, a high concentration of RFO reverses this trend, showing a paradoxical increase in MITF expression. This biphasic or hormetic response suggests that excessive exposure to carotenoid-rich compounds may induce oxidative stress or activate compensatory cellular mechanisms, thereby diminishing therapeutic efficacy. These findings underscore the importance of dose optimization when considering RFO for therapeutic applications. The observed modulation of MITF expression by RFO supports its ethnopharmacological use for skin health and highlights its potential role as a nutraceutical or cosmeceutical agent for managing hyperpigmentation disorders.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to extend their heartfelt appreciation to Ms. Susi for her invaluable technical support and assistance during the laboratory procedures. We would also like to express our sincere gratitude to the entire staff and personnel of the Central Laboratory of Universitas Padjadjaran (Lab Sentral Unpad) for their cooperation and support throughout the duration of this research. Their contributions were indispensable to the successful conclusion of this investigation.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Sri Trisnawaty: conceptualization and design of the research, data collection and analysis, writing the original draft; Julia Windi Gunadi: research concept and design, writing the article, and critical revision; and Hana Ratnawati: research concept and design, writing the article, and critical revision. All authors have reviewed and approved the final version of the article.