1. INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer is the most frequently diagnosed malignancy in women, with 2.3 million new cases and 670,000 deaths reported in 2022, and it now represents one in every eight cancers worldwide(Arnold et al., 2022). The World Health Organization projects that annual incidence could reach 3.2 million by 2050 if current trends continue, underscoring an urgent need for more effective preventive and therapeutic strategies. Although survival exceeds 90 % in many high-income regions, it remains below 70 % in low- and middle-income countries, revealing stark inequities in access to early diagnosis and targeted treatment (World Health Organization, 2023). Clinically, the heterogeneity of breast cancer, reflected in luminal, HER2-enriched, and triple-negative molecular subtypes, complicates management and fosters drug resistance (Harbeck and Gnant, 2017).

Despite the proliferation of targeted therapies, metastatic breast cancer remains the leading cause of cancer mortality in women (Xiong et al., 2025). Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is especially concerning as it accounts for a disproportionate share of deaths and still offers a median overall survival of 18 months (Xiong et al., 2024). Even in hormone-receptor-positive disease, ESR1 mutations also drive resistance to endocrine therapies and demand new therapeutic targets or novel therapies (Dustin et al., 2019). Consequently, there is interest in rapid discovery strategies, including drug repurposing, identifying novel treatment targets, and natural product mining, which can leverage existing safety data and reduce development times. Recent reviews have catalogued agents and phytochemicals with preclinical activity against breast cancer hallmarks (Shivani et al., 2024).

Recent integrative analyses that pooled 11 GEO studies and applied machine learning feature selection identified robust multigene signatures with high potency as clinical biomarkers (Yu et al., 2025). These highlight the power of meta-analysis using combined datasets to overcome small sample sizes and increase generalizability. Comparable pipeline designs have uncovered hub genes, defined as genes with high-degree nodes in protein-interaction networks, that orchestrate metastasis or therapy resistance. For example, altered expression of metabolic regulators such as PCK1 and LPL was linked to liver-recurrence risk in a 2024 study (Kwok and Chitrala, 2024). Beyond identifying transcripts, pan-cancer screens are starting to reveal pathway-level vulnerabilities; a 2025 study of ESCRT complex genes showed that VPS37D expression stratifies breast cancer prognosis and correlates with an immune-suppressive microenvironment, making the complex an attractive therapeutic target (Chen et al., 2025).

While these discoveries nominate targets, translating them into therapeutics increasingly relies on in-silico approaches. Several studies have shown that docking against estrogen-receptor-α screened phytoconstituents identified ginicidin as a submicromolar binder and a potential drug lead (Alagarsamy et al., 2025). Other studies use AutoDock to interrogate phytochemical compounds from Pleurotus ostreatus against ER, PR, and HER-2 and have identified drug-like molecules from their phenolic and flavonoid compounds (Effiong et al., 2024). Bioactive compounds from Moringa oleifera leaves were also shown to exhibit favourable docking characteristics toward hypoxia-regulated targets HIF-1α and VEGF, suggesting a route to inhibit angiogenesis in hypoxic breast tumours (Masarkar et al., 2025).

This study utilizes public breast-cancer transcriptomes from the GEO database to pinpoint disease-defining genes and pathways. We then couple the molecular insight gained with the protein–protein interaction (PPI) network to identify critical proteins relevant to breast carcinogenesis. The essential proteins will be subjected to an in silico search for existing drugs and bioactive natural compounds. By linking large-scale expression signatures with structure-guided ligand discovery and drug-likeness filtering, we seek to uncover affordable, mechanistic candidates that could complement current treatments and broaden the options for patients with breast cancer.

2. METHODS

2.1. Dataset collection and preprocessing

Two public breast cancer microarray datasets were obtained from the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO): GSE54002 (Tan et al., 2014) and GSE42568 (Clarke et al., 2013). Data were imported using the R package GEOQuery (Davis and Meltzer, 2007) version 3.21. Probe-level annotations were retrieved from the Gemma platform (Lim et al., 2021). Genes with missing annotations or ambiguous mappings were excluded from downstream analysis.

2.2. Differential expression and meta-analysis

Differential expression analysis was performed separately using the limma package in R (Ritchie et al., 2015). A meta-analysis of effect sizes was conducted to identify consensus differentially expressed genes. A fixed-effects inverse-variance model was used to calculate pooled estimates using the metafor package in R (Viechtbauer, 2010). Genes with p-values of less than < 0.05 were considered consensus DEGs.

2.3. Protein–protein interaction network construction and hub gene identification

Consensus DEGs were submitted to the STRING (Szklarczyk et al., 2023) database to construct a PPI network. The resulting network was visualized and analyzed in Cytoscape (Shannon et al., 2003) (v3.10.2). The hub genes were identified based on degree centrality.

2.4. Target protein structure retrieval

Three-dimensional structures of the identified hub proteins were retrieved from the Protein Data Bank. Protein structures were prepared using AutoDock Tools version 1.5.7 by removing water molecules, adding polar hydrogens, and assigning Kollman charges following the protocol by Forli et al. (2016).

2.5. Ligand selection and molecular docking

Ligands for virtual screening were compiled from a set of natural compounds from the KEGG Phytochemical Database. Ligand structures were energy-minimized and converted to PDBQT format using Open Babel (O’Boyle et al., 2011) and RDKit in Python. Molecular docking was performed using AutoDock Vina version 1.2.7 (Eberhardt et al., 2021). Binding affinity (kcal/mol) was recorded for each ligand-protein pair, and the top-scoring compounds were selected for further evaluation.

2.6. ADMET and drug-likeness evaluation

Top-ranking ligands were evaluated for their pharmacokinetic properties using ADMETLab 3.0. (Fu et al., 2024) Properties such as Lipinski’s Rule of Five, predicted oral bioavailability, blood–brain barrier permeability, toxicity, and cytochrome P450 inhibition were assessed. Compounds with favorable drug-likeness and ADMET profiles were prioritized as potential therapeutic candidates.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

We first analyzed differential expression on the two breast cancer microarray datasets, GSE54002 and GSE42568, containing gene expression profiles of primary breast tumors and adjacent normal tissues. After normalization and probe annotation using the Gemma platform, 20,420 unique genes were analyzed in each dataset. Differential expression analysis was performed, and for each dataset, we computed log2 fold changes and corresponding p-values to assess the expression differences between tumor and normal samples. We retained all genes for downstream meta-analysis to ensure that the identified DEGs were consistent. We then performed a meta-analysis of effect sizes by integrating the log2 fold changes and standard errors across both datasets. We used a fixed-effects inverse-variance model, calculating each gene’s pooled effect sizes and p-values.

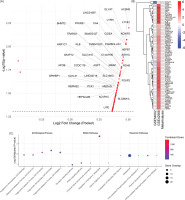

Notably, the gene list was enriched for established markers involved in lipid metabolism and transport, highlighting the pivotal role of metabolic reprogramming in breast cancer. Several of the top genes are key players in processes such as fatty acid β-oxidation (ACADL), lipid droplet remodeling (CIDEA and PNPLA2), and triglyceride hydrolysis (LIPE), as well as regulators of lipoprotein formation and lipid signaling (APOB, MLXIPL). This enrichment revealed the importance of lipid pathways in breast cancer progression and suggests that dysregulation of fatty acid metabolism may contribute to carcinogenesis. A volcano plot and heatmaps of the 77 overexpressed genes in both individual and pooled datasets are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Transcriptomic meta-analysis, expression patterns, and enrichment analysis of breast cancer-associated genes. (A) Volcano plot of the meta-analysis results showing pooled log2 fold change. Each dot represents a gene, with several significant genes labeled. The dashed horizontal line indicates the significance threshold (p = 0.05). (B) Combined heatmap of the 77 overexpressed genes across the two datasets (GSE54002 and GSE42568) and the pooled meta-analysis. Rows represent genes; columns represent the datasets. Colors indicate log2 fold changes, with red denoting upregulation and blue denoting downregulation.(C) Top 5 enriched terms for GO Biological Processes, KEGG Pathways, and Reactome pathways. The enrichment results prominently feature pathways related to lipid-associated processes such as triglyceride, acylglycerol metabolism, PPAR signaling pathway, and plasma lipoprotein modeling process. For each panel, the X-axis shows pathway names, and the Y-axis indicates –log10(Adjusted P-value). Dot sizes represent the number of overlapping genes, and dot colors reflect the Combined Score calculated from enrichR, with higher scores in red.

To characterize the biological roles of the 77 overexpressed genes, we performed enrichment analysis (Figure 1C) using multiple databases, including the Gene Ontology (GO) for biological processes, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways, and the Reactome database. Enrichment analysis was conducted using the EnrichR R package. In the KEGG pathway analysis, we identified that the most significantly enriched pathways included Regulation of lipolysis in adipocytes, PPAR signaling pathway, and Glucagon and AMPK signaling pathway. These pathways are involved in lipid metabolism and energy balance, which might reflect cancer cell metabolic reprogramming. GO enrichment highlighted processes tightly linked to lipid regulation and metabolism. Top-ranked terms included Triglyceride homeostasis, catabolic, metabolic process, and acylglycerol homeostasis. These findings reinforce the role of lipid metabolism and altered energy dynamics found in our breast cancer datasets. In the Reactome pathway analysis, key enriched pathways included PKA-mediated phosphorylation of key metabolic factors, plasma lipoprotein remodeling, and PP2A-mediated dephosphorylation of key metabolic factors. Further supporting that lipid metabolism and transport pathways may play important roles in breast cancer. The full meta-analysis results can be seen in the supplementary materials on Figshare (Sanjaya, 2025).

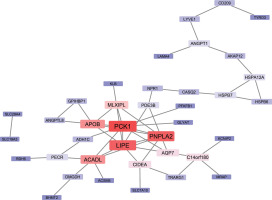

The 77 overexpressed genes were submitted to the STRING database using the default parameters to create a PPI network (Figure 2). The resulting network was visualized in Cytoscape and analyzed to evaluate the degree of centrality. We identified PCK1, PNPLA2, and LIPE as the top-ranking nodes, with Degrees of 9 and 8, respectively. Additional hub genes included ACADL, APOB, and MLXIPL. These genes are functionally linked to lipid metabolism and energy regulation, consistent with the enrichment analysis findings. The complete enrichment results can be seen in the supplementary materials on Figshare (Sanjaya, 2025).

Figure 2

Protein–protein interaction (PPI) network of the 77 overexpressed genes. The network highlights central hub genes involved in lipid metabolic processes, including PCK1, LIPE, PNPLA2, ACADL, and APOB. These genes exhibit high connectivity within the network. Surrounding nodes represent interacting genes, Red shades indicating higher centrality, and blue shades indicating lower centrality. The network highlights the pivotal role of lipid metabolism pathways and their interconnectedness in breast cancer biology.

We assessed the prognostic significance of the top hub genes (PCK1, PNPLA2, and LIPE) using overall survival (OS) data from the TCGA-BRCA cohort (Table 1). Gene expression was modeled as a continuous variable in Cox proportional hazards regression, adjusting for age at diagnosis, hormone receptor status, and tumor stage to account for clinical confounders. The analysis revealed that only PCK1 was significantly associated with OS. Higher PCK1 expression was linked to increased mortality risk (hazard ratio [HR]: 1.09, 95% CI: 1.01–1.17, p = 0.037), supporting its potential as an independent prognostic biomarker in breast cancer. PNPLA2 and LIPE were not significantly associated with OS (p > 0.05).

Table 1

Cox regression results of the Top 3 Hub genes from PPI network analysis

PCK1 was selected for molecular docking analysis to explore potential therapeutic compounds after its identification as a top hub gene and independent prognostic marker. The three-dimensional structure of human PCK1 was obtained from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB ID: 1NHX). The protein structure was prepared by removing the cocrystallized ligand and all nonessential heteroatoms, adding polar hydrogens, and assigning Kollman charges using AutoDock Tools. The docking site was defined based on the known active site of PCK1. A total of 2,846 phytochemical ligands were retrieved from the KEGG Phytochemical Database; however, due to preparation errors related to poor conformations, only 2,802 ligands were successfully docked. The top-scoring ligand, Quadrigemine A, demonstrated a binding energy of –11 kcal/mol, outperforming the cocrystallized cPEPCK inhibitor, 1-(2-Fluorobenzyl)-3-butyl-8-(N-acetyl-4-aminobenzyl)-xanthine, which exhibited a binding energy of –10.28 kcal/mol. The top 10% of compounds (n = 300) with the lowest docking energies were further evaluated for pharmacokinetic and drug-likeness. The full docking results are available in the supplementary materials on Figshare (Sanjaya, 2025).

ADMETLab 3.0 was employed to assess drug-likeness and toxicity endpoints. Of the 300 phytochemical compounds initially screened, 189 (63%) passed at least one medicinal chemistry rule (Figure 3A). After screening for synthetic accessibility and intestinal absorption, 38 compounds (12.7%) demonstrated acceptable values. Toxicity screening was done based on Ames and hERG parameters, with eight compounds (2.7%) meeting all criteria. These shortlisted candidates were retained for further analysis, with complete compound profiles preserved for downstream evaluation. Among the 300 screened compounds, only eight ligands passed the initial screening. The eight compounds passed toxicity and pharmacokinetic filtering and fulfilled at least one medicinal chemistry rule. Two compounds, including Ergocristine and Musca-aurin-II, did not satisfy Lipinski’s criteria but were retained due to strong binding affinity and high oral bioavailability. In fact, ergocristine exhibited the best docking energy (−9.93 kcal/mol) out of the eight shortlisted ligands. The full ADMET screening results can be found in the supplementary materials on Figshare (Sanjaya, 2025).

Figure 3

Workflow illustration of ligand screening and filtering and ADMET profiling of the top 8 phytochemical candidates. (A) The diagram illustrates the sequential filtering process applied to an initial pool of 300 phytochemical ligands. After the evaluation of the medicinal chemistry, 189 compounds passed the filter. Synthetic feasibility assessment further reduced the pool to 178 ligands. Subsequent human intestinal absorption (HIA) screening identified 38 ligands with favorable absorption properties, and final toxicity screening yielded eight ligands that successfully passed all filters. The eight ligands that passed the toxicity evaluation will be further analyzed for potential leads. (B) ADME properties predicted for each compound, including fraction unbound (green), plasma protein binding (orange), blood–brain barrier (BBB) permeability (blue), P-glycoprotein substrate status (purple), and human intestinal absorption (HIA, pink). None of the compounds were predicted to penetrate the blood–brain barrier. Ergocristine exhibited exceptionally high plasma protein binding, limiting its free drug concentration. (C) The toxicity profile heatmap shows the predicted probability of several selected toxic adverse effects, including AMES mutagenicity, hERG inhibition, drug-induced liver injury (DILI), and other specific organ toxicity. Several compounds, such as the luteolin derivatives, showed high predicted risk for DILI and hepatotoxicity, indicating the need for dose optimization and validation to minimize safety concerns. Note that almost all of the substances showed a high probability of ototoxicity. (D) CYP450 inhibition profile demonstrating low predicted inhibitory potential across major isoforms (CYP1A2, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP2D6, CYP3A4, CYP2B6). None of the compounds were predicted to act as major CYP inhibitors, suggesting a low risk of drug–drug interactions and compatibility for combination therapy.

ADMET profiling of the top eight candidate ligands was conducted using ADMETlab 3.0, focusing on key pharmacokinetic and safety parameters relevant to drug development. All compounds exhibited favorable human intestinal absorption (HIA), with predicted probabilities exceeding 70%, indicating good potential for oral bioavailability. None of the compounds were predicted to cross the blood-brain barrier, which may be favorable in minimizing central nervous system-related side effects (Figure 3B). However, this same property could limit their utility in treating brain metastases. Ergocristine stood out with exceptionally high plasma protein binding, which could cause a narrow therapeutic index. Most other ligands displayed moderate-to-high protein binding but within acceptable ranges for further development. Interestingly, five compounds: 4,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid, Musca-aurin-II, Quercetin 3,3',7-trissulfate, Luteolin 7-glucuronide, and Baicalin, were predicted to have a low probability (<50%) of being substrates for P-glycoprotein. This suggests these ligands may be less susceptible to efflux-mediated resistance, potentially enhancing their therapeutic effectiveness. Toxicity prediction also revealed that while most compounds had acceptable profiles, specific ligands exhibited elevated probabilities for adverse effects. Almost all of the compounds were predicted to be ototoxic, and most of the compounds showed high risk for drug-induced liver injury (DILI), hepatotoxicity, and nephrotoxicity (Figure 3C). It is worth noting that significant organ toxicity is also commonly observed with conventional chemotherapeutic agents, and a careful balance between efficacy and risk needs to be verified. These findings necessitate further exploration and are discussed in detail in the subsequent section. Two candidates, Carnosifloside I and 4,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid, displayed relatively low predicted toxicity across most categories. No compound demonstrated strong inhibition potential for major cytochrome P450 isoforms (CYP1A2, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP2D6, CYP3A4, or CYP2B6), indicating a low likelihood of drug–drug interactions (Figure 3D). All compounds also showed favorable binding energy similar to the cocrystallized ligand (Table 2).

Table 2

Binding energy and medicinal characteristics of the top 8 phytochemical candidates.

In this work, we utilized public transcriptomics data to discover novel therapeutic candidates for breast cancer. We conducted a meta-analysis of two independent GEO microarray datasets. We identified 77 genes consistently overexpressed in tumor versus normal tissue, with enrichment analyses pointing to a central role for lipid metabolism pathways, such as triglyceride catabolism, PPAR signaling, and lipoprotein remodeling, in breast cancer progression. Previous works have reported lipid metabolism as a central player in breast cancer progression (Wan et al., 2025; Zipinotti dos Santos et al., 2023). A recent study by Liu et al. also identified key lipid metabolic genes dysregulated in at least half of the 14 cancers they explored (Liu et al., 2023). These reflect the central role of lipid metabolism in carcinogenesis in breast and other types of cancers.

Within this gene set, PCK1 emerged as a central hub in the PPI network and an independent prognostic factor in TCGA-BRCA survival analysis. PCK1 expression has been implicated in oncogenic metabolic reprogramming, although with different effects depending on the organs. For example, PCK1 played an antioncogenic role in the liver and kidneys (Xiang et al., 2023, 2021) both major gluconeogenesis sites. In contrast, increased PCK1 is associated with oncogenic function in cancers such as the breast (Chen et al., 2024; Liu et al., 2024; Tang et al., 2021). Additionally, PCK1 catalyzes gluconeogenic flux and fuels other biosynthetic pathways, epigenetic modifications, and immune signaling, further influencing cancer biology (Shang et al., 2023). Targeting PCK1 has become a research focus in recent years. 3-Mercaptopicolinic acid (3-MPA), the prototypical PCK1 inhibitor, has been shown to overcome chemoresistance in melanoma cells (Ren et al., 2022). Additionally, studies using metformin and dexamethasone, which influence PCK1 function, have shown beneficial effects in inhibiting tumor growth and inducing cell cycle arrest (Liu et al., 2024). The prognostic significance of PCK1 and its multiple roles in cancer cell biology underscore its potential as a druggable target in breast cancer.

Our structure-guided screening against the PCK1 active site yielded several phytochemicals with superior binding energies compared to the cocrystallized inhibitor, notably quadrigemine A (–11 kcal/mol vs. –10.28 kcal/mol). However, this substance did not pass our ADMET filtering. Integrating docking scores with ADMET filtering via ADMETlab 3.0, we distilled an initial library of 2,846 compounds to eight lead candidates. All eight exhibited high predicted human intestinal absorption (>70%) and low blood–brain barrier penetration. Ergocristine is one of the candidates with the lowest binding energy. These ergot alkaloids have been researched for their cytotoxic effects against cancer cell lines (BAI et al., 2020; Mulac et al., 2013; Mulac and Humpf, 2011). However, the potential of toxic effects such as ergotism and its secondary cancer effects has slowed their exploration as anticancer agents (Mrusek et al., 2015). 4,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid has been directly evaluated for anticancer activity, with research by Lodise et al. reporting that the substance inhibits DU-145 prostate cancer cell proliferation (Lodise et al., 2019). However, it is unclear which are the molecular targets of this substance.

Baicalin and its aglycone baicalein are the eight candidates that have been most extensively studied. Multiple reviews have reported the anticancer effects of these substances (Wang et al., 2024; Zieniuk and Uğur, 2025). Several studies on breast cancer have demonstrated that baicalein induces ROS-mediated mitochondrial apoptosis in MCF-7 breast cancer cells (Bernasinska-Slomczewska et al., 2024), downregulates Bcl-2 (Zieniuk and Uğur, 2025), and targets the β-catenin signaling (Zhou et al., 2017). The luteolins have been thoroughly reviewed and have shown anticancer potential in breast, lung, and other types of cancers (Rauf et al., 2024; Rocchetti et al., 2023; Sakao et al., 2024). Luteolin has been shown to interact with several pathways in cancer pathogenesis, from cell cycle, apoptosis, to autophagy (Obaid A Alharbi et al., 2024; Rocchetti et al., 2023). However, the specific molecular targets remain unclear. Additionally, no literature has specifically explored the luteolin isoform we identified in our article, Luteolin 7-glucuronide and Luteolin 7-diglucuronide, presenting them as novel drug candidates with potential in targeting lipid metabolism. Although quercetin has been extensively reviewed for its anticancer properties (Sakao et al., 2024), quercetin 3,3', 7-trisulfate lacks any published anti-tumor studies. Musca-aurin-II and Carnosifloside I have also not been explored in the literature, highlighting them as novel candidates. These data underscore that while baicalin derivatives and 4,5-diCQA have demonstrated bioactivity in related contexts, most of our leads represent unexplored phytochemicals warranting de novo characterization in breast cancer models.

While most leads avoided central CYP450 inhibition, mitigating drug–drug interaction concerns, predicted organ-specific toxicities, particularly ototoxicity and high risks for DILI, hepatotoxicity, and nephrotoxicity, were prevalent. Drug-induced liver injury accounts for the most common cause of acute liver injury, with fatality rates from 10 to 50% (Hosack et al., 2023). However, many current agents also exhibit comparable or greater toxicity profiles, requiring careful dose titration and monitoring (Alkhaifi et al., 2025). For example, established agents such as cisplatin are a known cause of hepatic enzyme elevations (Satyam et al., 2024). Further research has explored combination therapy with potential hepatoprotective agents and has shown promise for these hepatotoxic drugs (Ruiz de Porras et al., 2023; Vincenzi et al., 2025). Several studies have explained approaches to limit toxic effects, including nanoparticles and nanoformulations (Li et al., 2024; Venturini et al., 2025), which can limit off-target responses, and early identification of toxicophores, which can help drug design and detect off-target toxicity early (Saganuwan, 2024; Singh et al., 2016; Stephenson et al., 2020). However, we argue that these toxicities are not uncommon among conventional chemotherapeutics and must be balanced against antitumor efficacy, especially since computationally predicted toxicities should serve as a prioritization tool, rather than eliminators. Two of our compounds, carnosifloside I and 4,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid, showed relatively lower risk across toxicity endpoints, supporting their prioritization for experimental validation. In vitro assays using human hepatocytes and renal cells, and in vivo pharmacokinetic and toxicokinetic studies, will be essential to confirm safety profiles and therapeutic windows. Nevertheless, our identification of high-affinity phytochemicals against PCK1 and relatively favorable ADMET profiles suggests these natural products could complement or inspire new small-molecule PCK1 inhibitors. Bridging metabolic targeting in cancer with phytochemical drug discovery.

In this article, we implemented multiple bioinformatics and virtual screening approaches to increase the robustness of our findings. Nevertheless, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, our results only provide valuable early prioritization, which is inherently dependent on algorithmic assumptions and current training data and might not reflect dynamic molecular interactions and in vivo complexity. Our PCK1 docking also only utilized a static crystal structure. Moreover, although ADMETlab 3.0 offers extensive pharmacokinetic and toxicity predictions, it may not accurately evaluate larger or highly conjugated natural products. Future studies should validate the binding of these top candidates, particularly Carnosifloside I, 4,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid, and Musca-aurin-II, to PCK1 using in vitro or in vivo assays. Follow-up studies may also explore transcriptomic and metabolic changes of breast cancer cells treated with these compounds to evaluate their downstream effects on immune functions, lipid metabolism, apoptosis, and cell cycle progression. In vivo toxicity and pharmacokinetics should be assessed for further lead development in appropriate preclinical models. Given PCK1’s role in regulating immune-related pathways, future work may also investigate whether its inhibition can sensitize tumors to immune checkpoint blockade.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, this study integrates transcriptomic, hub gene identification, molecular docking, and ADMET filtering to uncover potential phytochemical inhibitors of PCK1 in breast cancer. Our findings highlight the significance of lipid metabolic reprogramming in tumor progression and position PCK1 as a metabolically active, druggable target. Several candidate compounds identified herein, such as 4,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid and baicalin, are supported by prior evidence of bioactivity. In contrast, others, including Carnosifloside I and Musca-aurin-II, represent novel candidates with unexplored potential. This work lays a foundation for future experimental validation and development of metabolism-targeting phytochemicals in breast cancer.

Acknowledgments

The authors thanked Maranatha Christian University for providing the needed research facilities.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability

The transcriptomic datasets are publicly available in the Gene Expression Omnibus database under accession numbers GSE54002 and GSE42568. Supplementary materials, including meta-analysis results, enrichment analyses, molecular docking outputs, and ADMET screening data, are available via Figshare (Sanjaya, 2025) at: 10.6084/m9.figshare.29045123.v1

Authors’ contribution

Ardo Sanjaya and Fen Tih led conceptualization. Ardo Sanjaya and Fen Tih conducted formal analysis, while Ardo Sanjaya and Rafael Lungguk Dian Simanjuntak carried out the investigation and methodology. Ardo Sanjaya handled project administration and supervision. Fen Tih and Ardo Sanjaya performed validation. Fen Tih and Rafael Lungguk Dian Simanjuntak completed the visualization. The original draft was prepared by Fen Tih and Rafael Lungguk Dian Simanjuntak, and all authors contributed to the review and editing of the final manuscript.