1. INTRODUCTION

Green vegetables are key components of a nutritious diet, as they are rich in carbohydrates, fats, proteins, vitamins (A, C, and K), and minerals (iron, calcium, and potassium), which are crucial for bodily functions (Abbasi et al., 2013; Sahu and Dalai, 2020). Their high fiber content supports digestion and promotes gut health. Green vegetables contain both essential and nonessential trace elements. Essential trace elements, although needed in minute amounts, are crucial for our bodies to function correctly. In contrast, nonessential trace elements have no known biological role and can even be harmful in excess. Mineral’s contamination poses serious health risks, including developmental issues, organ damage, chronic diseases, and even cancer. Similar risks have been reported in previous studies on metal uptake in plants under different environmental and soil conditions (Butnariu et al., 2015). Therefore, understanding the concentrations of these elements in commonly consumed vegetables is crucial for assessing dietary intake and potential health risks.

Zinc (Zn), chromium (Cr), manganese (Mn), and calcium (Ca) are essential nutrients vital for human health, while cadmium (Cd) is a toxic heavy metal with no known biological function. Zinc supports immune function, wound healing, and cell growth (Beach et al., 1981); chromium aids blood sugar regulation; manganese acts as a cofactor for enzymes involved in metabolism and antioxidant defense; and calcium is essential for bone health, muscle function, and neural transmissions. Both the deficiency and excess of these essential elements can cause various health problems (Wessels, 2015). For instance, high zinc intake can interfere with copper absorption, while excess manganese can cause neurological symptoms. Cadmium exposure, primarily through contaminated food (Taiwo et al., 2021) and smoking (Zhang et al., 2019), can cause damage to the kidneys and bones. Maintaining a balanced diet rich in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains is generally sufficient to meet the daily requirements for these essential elements. Unfortunately, excessive use of inorganic fertilizers can lead to heavy metal accumulation in vegetables, posing potential health risks (Sagagi et al., 2022). Therefore, examining the mineral profiles of locally grown vegetables is essential to assess their nutritional quality and potential health risks.

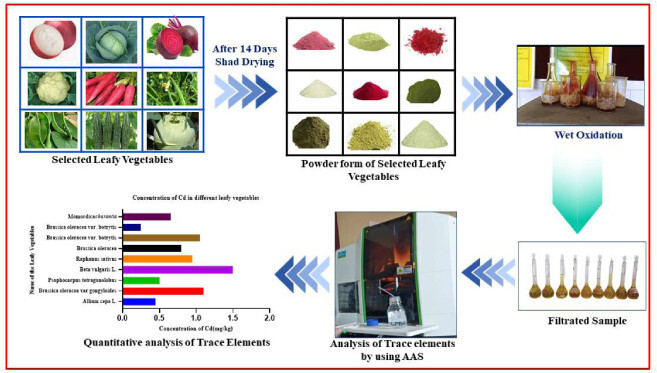

Recent studies have analyzed the nutrient composition of conventional green vegetables consumed in northeast India (Chandra et al., 2016). In West Bengal, green vegetables are an integral part of the diet, especially during the winters when there is an abundance of fresh produce. This includes a wide range of lesser-known seasonal greens, such as onion (bulb), cabbage (Leaves), kohlrabi (bulb) and cauliflower (flowering head), radish (root), beet (bulb), Immature Pods of winged beans, bitter gourd (fruit), and many more. Table 1 summarizes the common and regional names, phytoconstituents, and pharmacological activities of some winter greens commonly consumed in West Bengal. These vegetables are illustrated in Figure 1.

Table 1

Phytoconstituents and pharmacological activities of winter-grown vegetables commonly consumed in West Bengal, India.

Allium cepa L. (onion) is a widely cultivated vegetable valued for its culinary uses and health benefits. In regions like West Bengal, both the onion bulb and vegetables are consumed. Studies have shown that A. cepa L. has antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial properties, attributed to bioactive compounds like flavonoids, sulfur compounds, and phenolic acids (Bibi et al., 2022). Nemtinov et al. (2020) analyzed the mineral composition of A. cepa L. leaves and reported the presence of essential minerals such as iron, copper, zinc, and molybdenum. Beta vulgaris L. (beetroot) is valued for its sweet, edible root and highly nutritious leaves. It is a rich source of betalains (pigments responsible for its vibrant color), flavonoids, polyphenols, steroids, vitamins, and minerals, and exhibits antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anticancer, hepatoprotective, nephroprotective, and wound healing benefits (Schmidt et al., 1994; Sulakhiya et al., 2016). Raphanus sativus (radish) is a globally cultivated cruciferous vegetable with edible roots and leaves. R. sativus leaves and roots are used in traditional medicine for their potential anticancer, antimicrobial, and antiviral properties (Pérez Gutiérrez and Perez, 2004), attributed to bioactive compounds like glucosinolates, flavonoids, and phenolic acids

Brassica oleracea (wild cabbage) includes many common cultivars, such as kale, cabbage, and collard greens, recognized for their potential health benefits. Their rich phytochemical profile includes glucosinolates, phenolic compounds, and vitamins (Lee et al., 2017; Stansell et al., 2018).

These vegetables are good sources of minerals such as iron, nickel, zinc, manganese, copper, calcium, and selenium (Cámara-Martosa et al., 2021). B. oleracea var. gongylodes (kohlrabi) has both edible stems and leaves, with high mineral content and potential health benefits. Sassi et al. (2020) reported significant antioxidant and antibacterial activities in kohlrabi leaves, attributed to compounds like chlorogenic acid, catechol, and epicatechins. B. oleracea var. botrytis (cauliflower) is recognized for its edible flower heads that have anticancer, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant properties (Le et al., 2020; Salehi et al., 2021; Sousa et al., 2008).

Phaseolus vulgaris (common bean) is an herbaceous annual plant known for its edible seeds and pods, but its leaves are also edible. Several studies have reported that common bean landraces are rich in essential elements like iron, calcium, magnesium, selenium, and zinc (Akond et al., 2011; Celmeli et al., 2018), although copper, molybdenum, and potassium are also present (Bella et al., 2016). Lablab purpureus, commonly known as Indian bean or hyacinth bean, is a legume with a long history of use as both a food and traditional medicine. It is recognized for its potential pharmacological activities, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antidiabetic effects, which are attributed to its rich phytochemical profile that includes phenolic compounds, flavonoids, tannins, saponins, and alkaloids (Bhat et al., 2022). In addition , Lablab purpureus is known to be a good source of iron, zinc, and calcium. Momordica charantia (bitter gourd) is a tropical vine cultivated for its edible fruit, which has antioxidant, antidiabetic, anticancer, and antiviral properties (Lin et al., 2011). Bakare et al. (2010) reported the presence of various vitamins (A, E, folic acid, cyanocobalamin, and ascorbic acid) and minerals (potassium, sodium, calcium, zinc, magnesium, iron, manganese, and copper) in M. charantia leaves.

Understanding the nutrient profiles and potential contamination of commonly consumed winter vegetables is crucial for food safety and promoting healthy dietary habits in a specific region. However, no comprehensive study has reported the mineral composition of multiple winter-grown vegetables from West Bengal in a single dataset. Previous nutritional assessments in other Indian regions (Olaiya et al., 2015) and similar heavy metal profiling in vegetables from Nigeria (Emurotu et al., 2024) support the importance of such localized evaluations. In addition, although vegetables are known to be rich sources of essential nutrients, their mineral contents can vary due to differences in vegetables variety, growing conditions, soil composition, and agricultural practices. This is shown in studies on the influence of Co2+ ions on nutrient accumulation in soybean (Belkhodja et al., 2015) and the effect of NPK fertilizer dose on chlorophyll quality in corn plants. To address this knowledge gap, this study aimed to analyze the concentrations of some minerals—including zinc (Zn), chromium (Cr), cadmium (Cd), manganese (Mn), and calcium (Ca)—in nine green vegetables commonly consumed in West Bengal and assess the potential health risks associated with their consumption.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Sampling

Nine vegetables, including A. cepa L. (bulb), B. oleracea var. gongylodes (bulb), Lablab purpureus (immature pod), Beta vulgaris L. (bulb), R. sativus (roots), B. oleracea (leaves), B. oleracea var. botrytis (flower head), P. vulgaris (immature pod), and M. charantia (fruit), were collected from local markets of Deulbari, West Bengal. Different parts of the selected vegetables were thoroughly rinsed with water to remove any accumulated foreign matter, then treated with ethanol to remove surface contamination, and washed multiple times with deionized water followed by treatment with food-grade ethanol to remove surface contamination. All plant components were allowed to dry in shade for 14 days, then pulverized individually using a blender. All chemicals and solvents used in this study were of analytical grade.

2.2. Chemical digestion of plant samples

About 1 g of each powdered sample was digested in a nitric acid/perchloric acid (10:2) solution, following the wet digestion procedure (Karahan et al., 2020). The residual solution was dissolved in 2% nitric acid and diluted to 50 mL. The digested plant sample was then analyzed using an atomic absorption spectrophotometer.

2.3. Mineral analysis

Levels of five trace elements—Zn, Cr, Cd, Mn, and Ca—were measured using atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS), following a previously described method (Anal and Chase, 2016). Digested plant samples were diluted, filtered, and transferred to separate beakers. The solution was put into the oxidant-acetylene AAS. We used hollow cathode lamps to evaluate the elements’ absorbance at their resonance wavelengths. Table 2 summarizes the optimal operating conditions used for the AAS analysis.

2.4. Quality control and quality assurance

All chemicals used in this study were of analytical grade. Ultrapure water was used for all dilutions and experimental procedures. To ensure linearity, elemental analyses of these leafy vegetable samples were conducted in triplicate. Calibration standards were prepared and used to determine elemental concentrations with high precision, yielding a low relative standard deviation (RSD) of ±0.0108–0.2749% (Table 3). Elemental composition, including Ca, Cd, Cr, Mn, and Zn, was quantified using AAS.

Table 3

Analytical method parameters of AAS.

To quantify elemental concentrations in the medicinal plant samples, calibration standards were prepared by serial dilution of a 1000 mg/L AAS multielement standard solution (Merck). For each element under investigation, calibration curves were constructed using eight distinct concentration levels. These curves demonstrated high linearity, with coefficient of determination (R2) values exceeding 0.99 (Table 3).

To ensure the stability and accuracy of the initial calibration throughout the analysis, the calibration standards were reanalysed after every tenth sample during the experimental process. The margins of error for these interim checks were carefully monitored to confirm that the initial calibration parameters remained consistent for the duration of the analytical procedure.

To validate the accuracy and precision of the elemental analyses, repeated measurements were conducted using multielement calibration solutions of known concentrations. The analytical performance was further characterized by determining the limit of detection (LoD) and limit of quantification (LoQ) for each element. These limits were established through the analysis of 2% HNO3 solution, with the resulting values presented in Table 3, using the following formula:

LoD = 3.3 × SD (1)

LoQ = 10 × SD (2)

where SD denotes the standard deviation of ten replicates of the blank solution.

2.5. Risk assessment for toxic metals (Cd and Cr)

The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and World Health Organization (WHO) define the reference dose (mg/kg/day) for each metal (n). The daily average exposure dose (mg/kg/day) is referred to as the estimated daily intake (EDIn), while the target hazard quotient (THQ) of the hazardous metal is denoted by THQn. The hazard index (HI) was developed to quantify the carcinogenic health risks associated with numerous hazardous metal exposures. Consumption of medicinal herbs may expose individuals to several hazardous metals, thereby posing a risk to their overall health. Therefore, the EDI, THQ, and HI were determined to assess Cd and Cr exposure risks associated with the consumption of vegetables and potential health hazards for consumers.

where n represents the toxic metal (Cd or Cr), Cn represents the toxic metal concentration in plant samples (mg/kg), IR represents the plant’s uptake rate (11.4 g/person/day), TRn represents the toxic metal transference rate, and BW represents an adult person’s average body weight (70 kg). The TR values used in this investigation are 6.6% for Cd and 42% for Cr (Gruszecka-Kosowska and Mazur-Kajta, 2016; Li et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2018).

THQ was used to quantify the noncarcinogenic impact of each hazardous metal (Ozyigit et al., 2018), using the following equation:

where n represents the toxic metal (Cd or Cr) and EDIn represents the estimated daily intake of the toxic metal. A THQ score below 1 indicates no significant risk of carcinogenicity for the exposed population. The overall risk posed by various toxic metals to human health from consuming vegetables could result from exposure to several pollutants. To evaluate the cumulative health risks, including carcinogenic effects from multiple toxic metals, the HI was utilized.

In this equation, HI denotes the overall health risk from exposure to toxic metals. An HI value <1 suggests that the likelihood of harmful health effects from these metals is relatively low. Conversely, an HI value >1 indicates a higher probability of adverse health effects due to toxic metals.

2.6. Evaluation of recommended dietary allowance values

To determine the dietary reference intake potentials of A. cepa L., B. oleracea var. gongylodes, Lablab purpureus, Beta vulgaris L., R. sativus, B. oleracea, B. oleracea var. botrytis, P. vulgaris, and M. charantia used as daily food among the plants examined in this study, recommended dietary allowance (RDA) values were calculated for Ca, Mn, and Zn [37], using the following equation:

where, RDA (%) is the RDA percentages in 100 g/dw, MV is the mineral values in the studied plant samples (mg/kg or ppm), and RDAst is the international standard for RDA values (mg/100 g/dw).

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The mineral contents of the nine winter-grown vegetables analyzed in this study are summarized in Table 4. Plants require low concentrations of heavy metals to maintain their normal biochemistry and physiology. However, higher amounts of these elements can be harmful for both plant metabolism and human consumption (Nzediegwu et al., 2020). Long-term heavy metal exposure in plants can generate ROS, which can cause lipid peroxidation, enzyme inactivation, DNA damage, reduced respiration and gaseous exchange, reduced photosynthesis, water imbalance, and disrupted carbohydrate and nutrient uptake metabolisms. This can cause visible symptoms such as root blackening, necrosis, chlorosis, wilting, stunted plant growth, senescence, reduced biomass production, limited seed numbers, and even death. Excess Cd, Mn, or Zn intake can adversely affect multiple organ systems, including renal, neurological, and cardiovascular functions, as reported in previous toxicological studies (Altundag and Ozturk, 2011; Benítez et al., 2010; Egamberdieva and Öztürk, 2018; Gruszecka-Kosowska and Mazur-Kajta, 2016; Güvenç et al., 2012; Li et al., 2015; Moelling and Broecker, 2020; Nzediegwu et al., 2020; Ozyigit et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2018). Similar environmental contamination patterns have been observed in aquatic ecosystems, such as the heavy metal pollution documented in the Black Sea (Irshath et al., 2023). Therefore, while these minerals (except Cd) are essential for human physiology, it is crucial that their quantities remain within specified limits. Excessive levels of these minerals can lead to various health issues, indicating the importance of balanced mineral intake for maintaining optimal health.

Table 4

Mineral content in winter-grown vegetables.

The human body requires at least 20 minerals for proper metabolic functioning. Plants are the primary natural providers of these vital elements (Mükemre et al., 2015). Table 5 shows the RDA values for Ca, Mn, and Zn in A. cepa L., B. oleracea var. gongylodes, Lablab purpureus, Beta vulgaris L., R. sativus, B. oleracea, B. oleracea var. botrytis, P. vulgaris, and M. charantia, which are commonly consumed in West Bengal. The plants are arranged according to the detected RDA values (highest to lowest) as follows. Ca was detected in L. purpureus > B. oleracea var. botrytis > B. vulgaris L. > R. sativus > A. cepa L. > M. charantia > P. vulgaris > B. oleracea > B. oleracea var. gongylodes. Zn was detected in B. oleracea var. gongylodes > B. vulgaris L. > L. purpureus > R. sativus > P. vulgaris > B. oleracea > M. charantia > A. cepa L. > B. oleracea var. botrytis. Mn was detected in P. vulgaris > B. vulgaris L. > B. oleracea var. gongylodes > B. oleracea > L. purpureus > A. cepa L. > B. oleracea var. botrytis > R. sativus > M. charantia. These plants are noted for their edible nature, which highlights their potential use as nutritional supplements.

Table 5

Average level of selected minerals and %RDA values (mg/100 g) in the studied winter-grown vegetables.

Calcium (Ca) plays a crucial role in human health by influencing intracellular and extracellular processes, including the development, growth, and preservation of teeth and bones, as well as cytoskeleton integrity (Hakeem, 2018). It regulates vitamin D absorption, intracellular enzyme activity, and neural transmission (Kumar et al., 2018). Calcium insufficiency can cause congestive heart failure, cardiac arrhythmias, scurvy, sarcopenia, rickets, and osteoporosis in humans (Maurya et al., 2019). Dairy products are rich in calcium, with the recommended daily intake of 1000 mg. Our study indicated that B. oleracea var. gongylodes had the lowest RDA value for Ca (1.19%), while L. purpureus had the highest (10.19%; Table 5).

Manganese (Mn) is crucial for enzyme synthesis and activation, antioxidant defense, glucose and lipid metabolism, bone growth, hematopoiesis catalysis, immunological response, and neurological activities (White and Broadley, 2009; Ciosek et al., 2021). Dietary sources of Mn include cereals, rice, tea, and nuts. Mn deficiency can cause birth defects, reduced development and fertility, poor bone formation, aberrant glycosylation patterns, glucose and lipid metabolism, skeletal difficulties, and overall psychomotor impairment (Baj et al., 2020; Ciosek et al., 2021; Hosny et al., 1996; Wrzosek et al., 2019). The recommended daily intake of Mn is 2.3 mg for men and 1.8 mg for women, according to a study by Shenkin (Li and Yang, 2018). Our study indicated that Mn RDA value was the highest (650.22%) in P. vulgaris and the lowest (272.17%) in M. charantia (Table 5).

Zinc (Zn) is essential for bone construction, protein synthesis, immune system function, DNA synthesis, cell division, and pregnancy development, as well as growth during childhood and adolescence. It is involved in about 300 metalloenzymes, including Zn matrix metalloproteinases. Oysters, whole grains, crab, red meat, and beans are common sources of zinc in the diet (Bowman et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2021; Shenkin et al., 2003). According to WHO, the recommended daily intake of zinc is 11 mg for men and 8 mg for women. Our results show that B. oleracea var. botrytis has the lowest RDA value of Zn (11.45%), whereas B. oleracea var. gongylodes has the highest (48.95%) (Elements and Health, 2019; Kandasamy et al., 2020).

More than 60% of the world’s population is considered to be iron (Fe) deficient, while over 30% are zinc (Zn) deficient. Great deficiencies in Ca, Mg, and Cu are prevalent in both industrialized and developing countries (Mükemre et al., 2015). Our RDA results indicate that the plant species assessed in this study have high potential for acting as supplements of critical trace elements.

Chromium (Cr) is a crucial minerals with many sites of action and has a vital biological activity which is necessary in glucose homeostasis (Shayganfard et al., 2022). It regulates insulin and blood glucose levels by stimulating the insulin signaling pathway and metabolism, thereby improving insulin sensitivity. Modulation of lipid metabolism by Cr in peripheral tissues may represent an additional novel mechanism of action (Ozyigit et al., 2018). Deficiency of Cr or its biological active form has been implicated in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance and diabetes (Shayganfard, 2020).

Cadmium (Cd) is another harmful heavy metal that can significantly reduce plant output at concentrations between 5 and 30 mg/kg. It is becoming increasingly popular because of its widespread presence in water, soil, milk, food products, medicinal plants, and herbal products. Cadmium accumulates in soil and plants from various sources, including phosphate fertilizers, nonferrous smelters, lead and zinc mines, sewage sludge application, and fossil fuel combustion (Plum et al., 2010). Our study reveals that all examined plant samples had Cd concentrations within the WHO (2007) permissible limit for raw herbal material (0.3 ppm Cd) (Moon et al., 2022).

Our investigation revealed that the EDI, THQ, and HI values for the commonly consumed winter-grown vegetables in West Bengal were generally within acceptable ranges. The THQ levels and cumulative HI values for Cd and Cr indicate that exposure of adults to these two hazardous heavy metals is typically within acceptable limits for deleterious effects. Table 6 shows that A. cepa L. had the lowest HI value (0.10), whereas B. oleracea had the highest HI value (0.26) among the winter-grown vegetables examined in this study.

Table 6

EDI (mg/kg/day), THQ of Cd, Cr, Ni, and Pb and HI values for adults associated with the consumption of winter-grown vegetable samples in the study.

However, it is important to note that certain combinations of vegetables with higher Cd and Cr content could potentially exceed recommended HI values if consumed together. For instance, simultaneous consumption of B. oleracea (HI = 0.26), B. oleracea var. botrytis (HI = 0.16), Beta vulgaris L (HI = 0.15), M. charantia (HI = 0.14), P. vulgaris (HI = 0.16), and B. oleracea var. gongylodes (HI = 0.16) could result in a cumulative HI value exceeding the recommended range of one.

Assessing the hazardous index of toxic metals in vegetables is crucial for determining their impact on human health and accurately estimating their uptake through traditional use. This study underscores the importance of not only individual vegetable HI values but also the potential effects of consuming multiple high-HI vegetables simultaneously.

4. CONCLUSIONS

Anthropogenic activities such as mining, intensive agriculture, and fossil fuel combustion can lead to heavy metal contamination in soils, influencing the mineral profile of vegetables. The presence of highly toxic metals in soil poses significant risks to wildlife and human health, as consuming contaminated plants can be harmful. At the same time, the distribution of a sufficient quantity of essential minerals among commonly consumed seasonal vegetables is equally important for understanding their nutritional value.

To mitigate the risk of collecting contaminated vegetables, especially when sourcing therapeutic and aromatic herbs, it is crucial to select clean and remote areas. Ideal locations include rural areas near rivers and mountains, away from highways, mining operations, and industrial zones. Regular monitoring of heavy metal levels in vegetables through periodic analyses is essential, with results shared with local communities and resource managers. In this study, all examined winter-grown vegetables from West Bengal had mineral concentrations within internationally accepted safety limits, with notable variation among species. Heavy metal concentrations in the vegetables assessed were within acceptable levels.

Future research should focus on two key areas to address the limitations of this study. First, this study focused on a single region of West Bengal. Therefore, further investigations are required to explore the mineral content in vegetables across different regions to ensure that both heavy metal and beneficial mineral content are within safe limits. Comparison of the present findings with vegetables grown in other regions will offer a more comprehensive perspective on mineral quality and safety. Additionally, information on the distribution of essential minerals among various seasonal vegetables will enhance the knowledge of their nutritional value and contribute to more informed dietary choices. Second, although the vegetables selected for the present study are typically grown in winter, modern agricultural techniques now enable many of them to be grown year-round. Therefore, future investigations are necessary to evaluate the consistency in the essential mineral content of winter-grown vegetables compared to those grown in other seasons.