1. INTRODUCTION

Gingivitis is a common inflammation of the gums that is mostly caused by bacteria, especially when plaque builds up on teeth (Marchesan et al., 2020; Mehta et al., 2018b). It is the most common periodontal disease, and it usually manifests as chronic gingivitis, during which the gums become swollen, red, and bleeding. However, it is usually painless, so many people neglect treatment (Trombelli et al., 2018). The main treatment modality involves regular mechanical removal of the microbial plaque formed (Mehta et al., 2024). Treatments usually involve scaling and polishing, in addition to the placement of topical antibacterial agents such as chlorhexidine mouthwash. Aloe vera and green tea provide with some of the most effective herbal remedies for various oral conditions (Mathur et al., 2025; Mehta et al., 2018a). Most common treatment modalities include nonsurgical periodontic therapy such as scaling and polishing, and topical antibacterial agents like chlorhexidine mouthwash are often used as well. However, new research has shown that herbal alternatives from Ayurveda, an ancient Indian health system that focuses on overall health, may be beneficial. Ayurveda proposes multiple methods to keep the oral cavity healthy, one of which is Kavala or Gandusha, or oil pulling, which pertains to swishing oil inside the mouth. One of the most revered Ayurvedic texts, Charaka Samhita talks in detail about this method, which is thought to be able to heal about 30 systemic diseases, such as headaches, migraines, diabetes, and asthma. Ayurvedic remedies are important for controlling gum inflammation and improving general health because they work well and do not have many adverse effects.

Oil pulling is an ancient Indian folk medicine that has been used for a long time to prevent tooth decay, bad breath, bleeding gums, dry throat, chapped lips, and to make teeth, gums, and the jaw stronger (Asokan, 2008; Bethesda, 2006; Hebbar et al., 2010). Clinical and microbiological tests have revealed that oil pulling therapy works especially well for treating gingivitis caused by plaque (Asokan et al., 2009; Nagesh and Amith, 2007). Irimedadi taila is an Ayurvedic oil that is used for a lot of Ayurvedic procedures; however, it has not been a common choice for oil pulling. In the past few years, some studies have come out that talk about the benefits of Irimedadi oil. The oil is made from a wide range of Ayurvedic herbs, such as Yashti, Trijatha, Manjishta, Gayatri, Lodhra, Katphala, Kshirivrikshatwak, Irimeda twak, Musta, Agaru, Shvetachandana, Rakta chandana, Karpoora, Jati, Takkola, Mamsi, Dhataki, Gairika, Mrinala, Mishi, Vaidedi, Padmakesara, Kumkuma, Laksha, Samanga, Manjishta, Brihati, Bilvapatra, Suradruma, Shaileya, Sarala, Sprikka, Palasha, Rajani, Daruharidra, Priyangu, Tejani, Pradhakaleya, Pushkara, Jaya, Vyaghri, Madana, and Tila taila (Susruta and Bhishagratna, 1907).

We found a paucity of literature focused on the benefits of the usage of Irimedadi oil for oil pulling as well as comparative literature, providing a comparison between Irimedadi Taila and VCO for treating plaque-induced gingivitis. Thus, the purpose of this study was to analyze the effect of Irimedadi oil and VCO pulling as an adjunct for the treatment of plaque-induced gingivitis.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

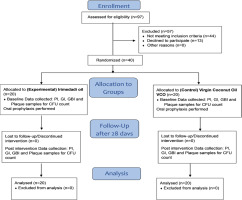

This research constitutes a randomized controlled trial focused on individuals aged 18-65 diagnosed with plaque-induced gingivitis, conducted at a dental facility in Pune. Ethical approval was secured from the Institutional Ethics Committee (DYPDCH/DPU/EC/583/185/2023), and the trial was registered with the Clinical Trials Registry, India. CTRI/2024/04/065946 The sample size was determined to be 40 individuals, calculated using a 95% confidence interval, 80% power, and a 5% alpha error. Participants were evaluated for oral hygiene and included if they possessed a minimum of 20 teeth, engaged in daily brushing, had not received periodontal therapy in the preceding 6 months, and demonstrated a GI score of ≥ 1 with bleeding upon probing and probing depth ≤ 3mm. The exclusion criteria were periodontal pockets measuring > 4mm, ongoing oil pulling activities, antibiotic treatment, pregnancy, allergies to herbal items, tobacco consumption, mouth breathing, or orthodontic interventions. Participants were allowed to withdraw from the study at any time. An individual examiner, trained and calibrated, performed the assessments, attaining a Cohen’s Kappa score of 0.83, signifying near-perfect concordance. For pilot testing, 10 eligible participants were chosen, and a case history sheet was created to document patient data, including age, sex, unique identification number, and various indices such as the Gingival Index by Loe and Silness (1963), Modified Plaque Index by Silness and Low (1964), Gingival Bleeding Index by Carter and Barnes (1974), and colony-forming units (CFU) count (Loe and Silness, 1963; Löe, 1967; Carter and Barnes, 1974).

Irimedadi taila was prepared at the institution’s Ayurved College by Dravyaguna MD personnel, using ingredients measured as per the standardised protocols of the Sushruta Samhita (Susruta and Bhishagratna, 1907), whereas the virgin coconut oil (VCO) was procured from a local, registered cold-pressed oil distributor. The main goal was to evaluate the impact of oil pulling as a supplementary treatment to periodontal care on gingival health. Participants received detailed information papers in English and Marathi, outlining the study’s objectives and methods, accompanied by consent forms to assure comprehension. They were directed to uphold a compliance document during the study. Following the collection of baseline data, oral prophylaxis was administered to all participants. The participants, examiner, and statistician were all blinded to mitigate selection and reporting bias. The research employed block randomization to allocate participants into two groups according to their initial gingival indices scores. Group 1 (experimental) was administered Irimedadi oil, while Group 2 (control) received VCO. The participants were randomly allocated into two groups utilising a Unique Identification Number by computer- generated software (Sealed Envelope Ltd., 2024). The SNOSE approach was utilized to guarantee allocation concealment, with oils supplied in indistinguishable, unmarked amber bottles. The examinations of participants were structured to eliminate contact between any two individuals to prevent contamination.

Plaque specimens were obtained at baseline and after 28 days. The samples were stored in Eppendorf vials containing 1 mL of normal saline. To preserve there integrity, the specimens are kept and transported at 4°C to the Microbiology Laboratory for analysis. The samples were diluted according to the Miles & Mishra technique. (Miles and Mishra, 1938) CFU counts were assessed under expert supervision. The CFUs were subjected to logarithmic transformation (Log10CFU) for subsequent analysis.

Statistical analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 21. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 21, Armonk, NY: IBM Corporation. Descriptive statistics, encompassing mean, standard deviation, frequency, and percentage, were calculated. The data’s normality was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests. Categorical variables were presented as counts and percentages, while continuous variables were articulated as averages and standard deviations (SD). An intention-to-treat analysis was performed. The Student’s paired t-test was utilized for continuous data, whereas the Mann-Whitney U test and Wilcoxon signed-rank test were employed for categorical data. The threshold for statistical significance was established at p<0.05.

3. RESULTS

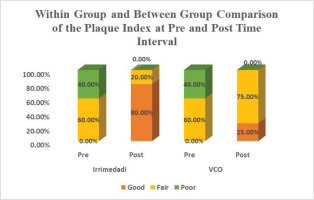

Normality of the data was assessed by Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests, verifying uniform distribution. The mean ages of participants were comparable in both groups: 43.80 ± 13.03 for the experimental group (Irimedadi) and 44.10 ± 13.30 for the control group (VCO). The gender distribution showed 40% males and 60% females in the Irimedadi group, but the VCO group had 65% males and 35% females, with no statistically significant difference. A comparative analysis of Plaque Index (PI) scores indicated significant improvements in the Irimedadi group, with 80% attaining favourable scores posttreatment, in contrast to merely 25% in the VCO group. Seventy-five percent of VCO participants achieved fair marks. The enhancement in favourable PI scores from pretreatment to posttreatment was statistically significant for both groups. At the pretreatment stage, no significant difference was observed between groups; however, a significant difference was noted posttreatment (P < 0.05) (Table 1; Figure 2).

Figure 2

Within-group and between-group comparison of the plaque index at pre- and post-time interval.

Table 1

Within-group and between-group comparison of the Plaque Index at pre- and post-time interval.

| Group | p Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Irrimedadi | VCO | |||||

| n | % | % | ||||

| PI pre | Good | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.000 |

| Fair | 12 | 60 | 12 | 60 | ||

| Poor | 8 | 40 | 8 | 40 | ||

| PI post | Good | 16 | 80 | 5 | 25 | 0.012* |

| Fair | 4 | 20 | 15 | 75 | ||

| Poor | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Total | 20 | 100 | 20 | 100 | ||

| p Value | 0.001$ | 0.001$ | ||||

On comparing the effects of Irimedadi oil (Group 1) and VCO (Group 2) on plaque index scores revealed that the experimental group exhibited a significant mean change in pre- and postinterventional scores from 1.77 ± 0.4 to 0.68 ± 0.2, yielding a mean difference of 1.09 (P < 0.05). The control group exhibited scores of 1.76 ± 0.38 and 1.03 ± 0.37, resulting in a mean difference of 0.735 (P < 0.05). The overall mean change in scores was −1.09 ± 0.48 for the experimental group and −0.735 ± 0.47 for the control group, resulting in a mean difference of −0.35. The disparity in the proportion was determined to be statistically significant (P < 0.05) (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2

Pre-post intervention scores of Plaque Index.

Table 3

Comparison of mean change in PI score (Post-Pre) between Irrimedadi and VCO group.

| Group | Mean | Std. deviation | Std. error mean | Mean difference | t | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean change in PI score (post -pre) | Irrimedadi | −1.09 | 0.483 | 0.108 | −0.355 | −2.348 | 0.024* |

| 0.473 | 0.106 | _ | |||||

The evaluation of the effects of Irrimedadi oil on gingival health by comparing GI) scores between an experimental group and a control group was performed. The experimental group showed a notable improvement post-intervention, with good scores rising from 5% to 70%. Conversely, the control group had only 30% achieving good scores, while 70% scored fair. Statistical analysis indicated no significant differences in preintervention scores, but significant differences emerged postintervention (P < 0.05), suggesting that Irrimedadi oil positively impacts gingival health (Table 4; Figure 3).

Figure 3

Within-group and between-group comparison of the gingival index at pre- and post-time interval.

Table 4

Within-group and between-group comparison of the Gingival index at pre- and post-time interval.

| Group | p value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Irrimedadi | VCO | |||||

| n | % | n | % | |||

| GI pre | Good | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0.495 |

| Fair | 13 | 65 | 12 | 60 | ||

| Poor | 6 | 30 | 8 | 40 | ||

| GI post | Good | 14 | 70 | 6 | 30 | 0.030* |

| Fair | 6 | 30 | 14 | 70 | ||

| Poor | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| p Value | 0.001$ | 0.001$ | ||||

Irimedadi oil (experimental) group’s mean GI score showed a reduction from 1.92 to 0.935, while the control group decreased from 1.98 to 1.29 both showing significant changes (P < 0.05). The mean change in GI scores was −0.98 for the experimental group and −0.69 for the control group, with a significant difference of −0.29 (P < 0.05). Overall, the findings support the efficacy of Irrimedadi oil in improving gingival health compared to the control (Tables 5 and 6).

Table 5

Pre-post intervention scores of Gingival Index.

Table 6

Comparison of mean change in GI score (post-pre) between Irrimedadi and VCO group.

| Group | Mean | Std. deviation | Std. error mean | Mean difference | t | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean change in GI score (post -pre) | Irrimedadi | −0.985 | 0.467 | 0.104 | −0.29 | −2.068 | 0.046* |

| VCO | −0.695 | 0.419 | 0.094 |

This study assessed the Gingival Bleeding Index (GBI) scores for two cohorts: an experimental group (Group 1) and a control group (Group 2) prior to and during the intervention. Group 1 showed a significant reduction in mean GBI scores from 13.65 ± 4.14 to 2.85 ± 1.69, with a mean difference of 10.8 (P < 0.05). Group 2’s scores changed from 14.1 ± 3.33 to 6.5 ± 3.83, exhibiting a mean difference of 7.6 (P < 0.05). The comparison indicated that the experimental group exhibited a larger mean change (−10.8 ± 3.5) compared to the control group (−7.6 ± 3.71), with a statistically significant difference (P < 0.05) (Tables 7 and 8).

Table 7

Pre-post intervention scores of gingival bleeding index.

Table 8

Comparison of mean change in GBI score (post-pre) between Irimedadi and VCO group.

| Group_Mean | Std. deviation | Std. error mean | Mean difference | t | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean change in GBI score (post-pre) | Irrimedadi | −10.8 | 3.548 | 0.793 | −3.2 | −2.784 | 0.008* |

| 3.719 | 0.832 | _ | |||||

Plaque samples were collected at baseline and after 28 days of intervention to evaluate CFUs. The experimental group (Group 1) exhibited a substantial decrease in mean colonies from 147.95 ± 88 to 10.25 ± 10.57, resulting in a mean difference of 137.7. The control group (Group 2) similarly diminished from 164.45 ± 79.1 to 108 ± 67. The analysis indicated that the experimental group exhibited a mean change of −137.7 ± 84, compared to −56.45 ± 46.2 for the control group, with both differences being statistically significant (P < 0.05) (Tables 9 and 10).

Table 9

Pre−post intervention scores of colony-forming units Group 1: Irimedadi oil group.

4. DISCUSSION

This study examines and compares the efficacy of Irimedadi oil and VCO as adjunctive treatments for plaque-induced gingivitis, concentrating on their microbiological effects. An exhaustive investigative study was performed to determine the effect of achieving these objectives. Prior studies, including those by Kothiwale et al. (2014), substantiate the effectiveness of oil in enhancing gingival health, irrespective of oil pulling. The research contrasted an herbal mouthwash containing tea tree oil, clove, and basil with a commercial essential oil mouthwash. Forty participants were randomly assigned to control and experimental groups, with PI, GI, and papillary marginal attachment (PMA) assessed at baseline, 14 days, and 21 days. The findings demonstrated a significant reduction in PI scores from 1.63 to 0.59 and GI scores from 1.59 to 0.38 by Day 21 (p < 0.0001). The PMA index considerably declined, and CFU counts from plaque samples decreased from 105.3 to 102.09, suggesting the efficacy of these oils in treating gingivitis.

The study corroborates previous research by Fida et al. (2018), which assessed clinical parameters such as PI, GI, GBI, and Modified Sulcular Bleeding Index in two cohorts: a control group receiving only scaling and an experimental group undergoing gingival massage with Irimedadi oil. The findings indicated that the experimental group experienced a significant reduction in PI and GBI compared to the control group. Peedikayil et al. (2015) conducted a trial utilising coconut oil pulling for the management of plaque-induced gingivitis, revealing a substantial decrease in PI from baseline to day 30. In contrast, the earlier report from Asokan et al. (2009) showed oil pulling against chlorhexidine mouthwash, although both had overall reductions, but no significant differences between the two groups in GI or PI. The experimental group utilising oil pulling had pre- and post-intervention scores of 1.262 ± 0.324 to 0.210 ± 0.155 for GI, whereas the control group demonstrated alterations from 1.308 ± 0.311 to 0.289 ± 0.187. Both groups exhibited a reduction in CFUs; however, the differences lacked statistical significance. The studies indicate differing efficacy among various oral hygiene methods.

Another study conducted by Bhate et al. (2015) evaluated the effects of a 0.12% chlorhexidine mouthwash and a herbal oral rinse on gingivitis induced by dental plaque, revealing comparable baseline PI and GI scores to those observed in the present study. This research concentrated on comparing two oils for oil pulling therapy, instead of chlorhexidine. Research conducted by Siripaiboonpong et al. (2022) evaluated oil pulling using VCO in comparison to palm oil, with a sample of 36 volunteers aged 19 to 29. Following the intervention, the GI scores diminished; nevertheless, the study of bacterial load revealed no significant effect of VCO on microbial counts. Patil et al. (2018) demonstrated alterations in GI scores, revealing a substantial decrease in the experimental group relative to the control group. Woolley et al. (2020) performed a review of four randomised controlled studies on coconut oil pulling, encompassing 182 participants, and saw significant reductions in salivary bacterial counts and PI. The research identified a substantial risk of bias and an absence of extensive literature on oil pulling, advocating for more rigorously conducted studies to obtain credible results. These studies jointly underscore the possible advantages of alternate oral hygiene methods and advocate for additional studies to corroborate the findings.

The duration of this study was determined according to the plaque renewal model; nevertheless, long-term alterations in periodontal health among persons who consistently practise oil pulling require evaluation. Subsequent research may employ a crossover design and prolong the period to 3-6 months, targeting certain demographics such as pregnant women or older persons to obtain more profound insights into the impact of oil pulling on oral health.

5. CONCLUSION

The research revealed significant reductions in PI, GI, GBI scores, and bacterial load after treatments with Irimedadi taila and VCO. Irimedadi taila proved to be palatably acceptable and demonstrated a more pronounced reduction in these scores compared to VCO and can be deemed highly successful in alleviating plaque-induced gingival inflammation, indicating its potential as an outstanding oral health intervention.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA

All data generated or analyzed during this study are available within the manuscript.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

Ethical approval was secured from the Institutional Ethics Committee (DYPDCH/DPU/EC/583/185/2023), and the trial was registered with the Clinical Trials Registry, India (CTRI/2024/04/065946).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization - I.I., An.M.; Data curation - L.R., C.B.; Formal analysis - I.I., L.R.; Investigation - An.M., R.A.; Resources - I.I., A.M.; Methodology - I.I., R.A.; Supervision - L.R., A.M.; Project administration - L.R., A.M. Validation - L.R.; Visualization - I.I., An.M.; Writing—original draft - I.I., An.M., C.B.; and Writing—review & editing - L.R., R.A., A.M.