1. INTRODUCTION

Endodontic infections involve diverse bacterial species that colonise the root canal system (Stuart et al., 2006). Enterococcus faecalis is notable for its ability to survive root canal treatment and contribute to post-treatment disease and failure (Prabhakar et al., 2010; Stuart et al., 2006). This pathogen can persist in nutrient-poor environments, penetrate deep into dentinal tubules, and form biofilms that resist standard disinfection methods (Prabhakar et al., 2010). The frequent use of systemic and local antibiotics in dental practice has promoted the emergence of multidrug-resistant strains, thereby reducing the effectiveness of conventional therapies (AL-Azzawi et al., 2015). Common irrigants such as 5% sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) and 2% chlorhexidine (CHX) demonstrate strong antimicrobial effects. NaOCl dissolves organic tissue, while CHX maintains antibacterial activity over time (Prabhakar et al., 2010; Kanisavaran, 2008). These agents have limitations: CHX can be cytotoxic at higher concentrations, both may leave an unpleasant taste or odour, they do not entirely remove biofilms from dentinal tubules, cannot eliminate the inorganic portion of the smear layer, and lack regenerative capacity (Kanisavaran, 2008; Reshma Raj et al., 2020; Susan et al., 2019).

Herbal alternatives derived from medicinal plants have gained attention as potential endodontic irrigants and intracanal medicaments due to their antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and regenerative properties. Table 1 summarises commonly studied herbal products, their source or composition, key effects in endodontics, mechanisms of action, and supporting references. This table provides a concise overview of agents such as Triphala, green tea, neem, Morinda citrifolia, curcumin, propolis, and turmeric, highlighting their activity against resistant bacteria, biofilm disruption, cytocompatibility, and potential to preserve dentin and support pulp tissue regeneration. This review assesses the current evidence on herbal endodontic irrigants and intracanal medicaments, with a focus on their antimicrobial efficacy, cytocompatibility, anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, and regenerative potential. The review also highlights the lack of standardised concentrations, the limited information on prolonged outcomes, and the need for direct comparison with conventional irrigants.

Table 1

Common herbal endodontic irrigants and intracanal medicaments, their sources, key effects, and mechanisms of action.

| Herbal agent | Effects | Mechanism of action | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Triphala | Terminalia chebula, T. bellirica, Emblica officinalis | Reduces E. faecalis, removes smear layer, decreases biofilm, and reduces postoperative pain/flare-ups | Antimicrobial, smear layer removal, anti-inflammatory | (Alghamdi et al., 2024; Garg et al., 2014; Kishan et al., 2025; Prabhakar et al., 2010, 2015; ReshmaRaj et al., 2020; Somayaji et al., 2014; Susan et al., 2019; Selvi et al., 2022) |

| Green Tea | Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (polyphenols) | Inhibits biofilm, reduces bacterial adhesion, preserves dentin microhardness, and is synergistic with irrigants | Antimicrobial, anti-biofilm, dentin protection | (Chandran et al., 2024; Gondi et al., 2021; Hormozi, 2016; Liao et al., 2020; Murali et al., 2017; Ramezanali et al., 2016; Trilaksana and Saraswati, 2016) |

| Neem | Azadirachta indica | Antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, maintains pulp vitality | Broad-spectrum antibacterial | (Alghamdi et al., 2024; Agnihotri et al., 2020; Bhargava et al., 2015; Dutta and Kundabala, 2014; Palombo, 2011; Lee et al., 2017; Saxena et al., 2017) |

| Morinda citrifolia | Noni fruit extracts | Reduces bacterial load, supports healing, and maintains dentin microhardness | Antimicrobial, tissue regeneration | (Afshan et al., 2020; Chandwani et al., 2017; Divia et al., 2018; Garg et al., 2014; Gondi et al., 2021; Omar et al., 2012; Podar et al., 2015; Songsiripradubboon et al., 2016) |

| Curcumin | Curcuma longa | Antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory supports regeneration | Antimicrobial, tissue healing | (Brar et al., 2019; Dedhia et al., 2018; Swapnil et al., 2017) |

| Emblica officinalis | Amla fruit | Antioxidant protects pulp cells from oxidative stress | Antioxidant, cytoprotection | (Lee et al., 2017; Prakash and Shelke, 2014; Shanbhag, 2015) |

| Propolis | Bee resin extract | Antimicrobial, inhibits biofilm, reduces inflammation | Antimicrobial, anti-biofilm | (Darag et al., 2017; Mali et al., 2018; Oak et al., 2023; Sivakumar et al., 2018; Venkateshbabu et al., 2016; Tyagi et al., 2013) |

| Turmeric | Curcuma longa | Inhibits resistant E. faecalis, reduces inflammation | Antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory | (Brar et al., 2019; Dedhia et al., 2018; Kishan et al., 2025) |

| Terminalia chebula | Part of Triphala | Enhances antibacterial outcomes, antioxidant | Antimicrobial, antioxidant | (Alghamdi et al., 2024; Lee et al., 2017; Shanbhag, 2015) |

2. ANTIBIOTIC RESISTANCE IN ENDODONTICS

2.1. Mechanisms of bacterial resistance

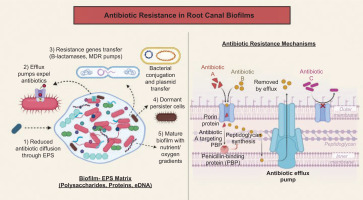

Bacteria in endodontic infections resist conventional antimicrobial strategies through several mechanisms. E. faecalis helps in the formation of dense biofilms, which restrict antibiotics and irrigants from reaching the cells (Nour El Deen et al., 2017; Stuart et al., 2006). Biofilms form microenvironments that protect bacteria from various forms of stress. Bacteria acquire resistance through plasmids, expel antibiotics using efflux pumps, and modify drug targets through mutations or enzymes (Al-Azzawi et al., 2024). Horizontal gene transfer facilitates the spread of resistance in endodontic bacteria, resulting in the development of multidrug-resistant strains. E. faecalis alters its cell wall and produces stress proteins, lowering NaOCl and CHX susceptibility (Alaqeel et al., 2023; Stuart et al., 2006). Dormant persister cells in biofilms survive potent antimicrobials and can repopulate the canal, leading to recurrent or persistent apical periodontitis (Kishan et al., 2025; Tewari et al., 2016). Figure 1 illustrates how biofilms in root canals use EPS barriers, efflux pumps, horizontal gene transfer, and persister cells to resist treatment.

Figure 1

. Antibiotic resistance illustrates how bacterial biofilms in root canals develop antibiotic resistance through multiple mechanisms, including reduced antibiotic diffusion via the EPS matrix, efflux pumps, horizontal gene transfer of resistance genes, and the formation of dormant persister cells. The right panel details specific molecular resistance strategies, such as antibiotic modification, target alteration (e.g., PBP mutation), efflux pump expulsion, and physical barrier formation, which prevent antibiotic entry.

2.2. Clinical Impact

High E. faecalis concentrations of NaOCl or CHX may fail to eliminate mature biofilms, particularly in complex anatomical areas such as isthmuses and apical deltas (Divia et al., 2018; Prabhakar et al., 2010; Somayaji et al., 2014). The limitations of conventional irrigants have led to the exploration of herbal alternatives. Triphala, green tea, neem, and Morinda citrifolia extracts show antimicrobial effects against biofilm E. faecalis, sometimes matching NaOCl efficacy (Agrawal and Kapoor Agrawal, 2017; Divia et al., 2018; Brar et al., 2019; Garg et al., 2014; Pathivada et al., 2024; Choudhary et al., 2018; Pujar et al., 2011; Trilaksana and Saraswati, 2016). They help disrupt bacterial cell walls, inhibit adhesion, and suppress virulence gene expression, thereby reducing the potential for resistance development (Anwar et al., 2025; Palombo, 2011; Agnihotri et al., 2020). Validated herbal agents, combined with mechanical and chemical disinfection, manage resistant endodontic infections and improve treatment outcomes (Agrawal and Kapoor, 2017; Das et al., 2024; Oak et al., 2023; Susila et al., 2023; Vitali et al., 2022; Venkateshbabu et al., 2016).

3. RATIONALE FOR HERBAL ALTERNATIVES IN ENDODONTICS

3.1. Broad-spectrum bioactivity

Herbal agents offer antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory properties that address various aspects of endodontic infections. Plant-derived compounds target multiple bacterial pathways simultaneously, thereby reducing the risk of resistance development (Anwar et al., 2025). Polyphenols in green tea (epigallocatechin-3-gallate) disrupt bacterial membranes, inhibit enzyme activity, and suppress biofilm formation through interference with quorum-sensing pathways (Chandran et al., 2024; Liao et al., 2020; Hormozi, 2016; Ramezanali et al., 2016). Triphala, a combination of Terminalia chebula, Terminalia bellirica, and Emblica officinalis, exerts synergistic effects via tannins, gallic acid, and flavonoids, damaging microbial cell walls, denaturing proteins, and chelating essential metal ions (Brar et al., 2019; Prabhakar et al., 2010; Prakash and Shelke, 2014; Shanbhag, 2015).

Neem (Azadirachta indica) contains nimbidin and azadirachtin, which inhibit adhesion and hyphal formation in Enterococcus faecalis, Streptococcus mutans, and Candida albicans (Agnihotri et al., 2020; Dedhia et al., 2018; Dutta and Kundabala, 2014; Palombo, 2011). Morinda citrifolia juice disrupts proton motive force and ATP synthesis, leading to rapid bacterial death (Choudhary et al., 2018; Divia et al., 2018; Garg et al., 2014; Podar et al., 2015). Curcumin from Curcuma longa downregulates virulence genes and reduces oxidative stress in periapical tissues (Brar et al., 2019; Dedhia et al., 2018). These mechanisms allow herbal agents to reduce bacterial load without promoting resistance, unlike single-target antibiotics (Anwar et al., 2025; Agnihotri et al., 2020; Palombo, 2011). In vitro studies demonstrate that herbal irrigants such as Triphala, green tea, and neem achieve log reductions in E. faecalis biofilms comparable to 5.25% sodium hypochlorite (Alghamdi et al., 2024; Divia et al., 2018; Prabhakar et al., 2010; Pujar et al., 2011; Shakouie et al., 2014). These findings validate their antimicrobial efficacy and support their use as adjuncts in root canal therapy.

3.2. Biocompatibility and regenerative potential

Herbal compounds also support tissue repair and regeneration. Ascorbic acid enhances proliferation, secretome production, and stemness of stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth (SHEDs), promoting pulp-dentin complex regeneration (Bhandi et al., 2021; Diederich et al., 2023). Genipin from Gardenia jasminoides upregulates odontogenic markers (DSPP, DMP-1) in human dental pulp cells and acts as a natural cross-linker to improve scaffold stability during regenerative procedures (Kwon et al., 2015). Acemannan from Aloe vera stimulates dentin bridge formation and shows favourable histological outcomes in direct pulp capping (Songsiripradubboon et al., 2016). Nigella sativa oil reduces inflammatory infiltrates and supports healthy pulp architecture when used in pulpotomy (Omar et al., 2012).

Herbal irrigants exhibit lower cytotoxicity compared to conventional agents such as sodium hypochlorite and CHX. Triphala and green tea polyphenols maintain fibroblast viability and preserve radicular dentin microhardness (Devi et al., 2019; Reshma Raj et al., 2020; Gondi et al., 2021; Murali et al., 2017). Propolis and Terminalia chebula extracts reduce microbial load with minimal tissue irritation (Lee et al., 2017; Tyagi et al., 2013). Clinically, intracanal medicaments containing Triphala, neem, or Morinda citrifolia produce fewer interappointment flare-ups and less postoperative pain compared to calcium hydroxide or formocresol (Kishan et al., 2025; Pathivada et al., 2024). Herbal alternatives combine effective microbial control with biocompatibility and regenerative support. They disinfect without cytotoxicity, modulate inflammation, and stimulate stem cell-mediated repair, making them suitable adjuncts in contemporary endodontic therapy (Agrawal and Kapoor Agrawal, 2017; Anwar et al., 2025; Susila et al., 2023; Vitali et al., 2022).

4. RATIONALE FOR HERBAL ALTERNATIVES IN ENDODONTICS

Herbal agents offer antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory properties that address various aspects of endodontic infections. Plant-derived compounds target multiple bacterial pathways simultaneously, thereby reducing the risk of resistance development (Anwar et al., 2025). Polyphenols in green tea (epigallocatechin-3-gallate) disrupt bacterial membranes, inhibit enzyme activity, and suppress biofilm formation through interference with quorum-sensing pathways (Chandran et al., 2024; Hormozi, 2016; Liao et al., 2020; Ramezanali et al., 2016). Triphala, a combination of Terminalia chebula, Terminalia bellirica, and Emblica officinalis, exerts synergistic effects via tannins, gallic acid, and flavonoids, damaging microbial cell walls, denaturing proteins, and chelating essential metal ions (Brar et al., 2019; Prabhakar et al., 2010; Prakash and Shelke, 2014; Shanbhag, 2015).

Neem (Azadirachta indica) contains nimbidin and azadirachtin, which inhibit adhesion and hyphal formation in Enterococcus faecalis, Streptococcus mutans, and C. albicans (Agnihotri et al., 2020; Dedhia et al., 2018; Dutta and Kundabala, 2014; Palombo, 2011). Morinda citrifolia juice disrupts proton motive force and ATP synthesis, leading to rapid bacterial death (Divia et al., 2018; Garg et al., 2014; Podar et al., 2015; Choudhary et al., 2018). Curcumin from Curcuma longa downregulates virulence genes and reduces oxidative stress in periapical tissues (Brar et al., 2019; Dedhia et al., 2018). These mechanisms allow herbal agents to reduce bacterial load without promoting resistance, unlike single-target antibiotics (Anwar et al., 2025; Palombo, 2011; Agnihotri et al., 2020). In vitro studies demonstrate that herbal irrigants such as Triphala, green tea, and neem achieve log reductions in E. faecalis biofilms comparable to 5.25% sodium hypochlorite (Alghamdi et al., 2024; Divia et al., 2018; Prabhakar et al., 2010; Pujar et al., 2011; Shakouie et al., 2014). These findings validate their antimicrobial efficacy and support their use as adjuncts in root canal therapy.

4.1. Biocompatibility and regenerative potential

Herbal compounds also support tissue repair and regeneration. Ascorbic acid enhances proliferation, secretome production, and stemness of stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth (SHEDs), promoting pulp-dentin complex regeneration (Bhandi et al., 2021; Diederich et al., 2023). Genipin from Gardenia jasminoides upregulates odontogenic markers (DSPP, DMP-1) in human dental pulp cells and acts as a natural cross-linker to improve scaffold stability during regenerative procedures (Kwon et al., 2015). Acemannan from Aloe vera stimulates dentin bridge formation and shows favourable histological outcomes in direct pulp capping (Songsiripradubboon et al., 2016). Nigella sativa oil reduces inflammatory infiltrates and supports healthy pulp architecture when used in pulpotomy (Omar et al., 2012).

Herbal irrigants exhibit lower cytotoxicity compared to conventional agents, such as sodium hypochlorite and CHX. Triphala and green tea polyphenols maintain fibroblast viability and preserve radicular dentin microhardness (Devi et al., 2019; Reshma Raj et al., 2020; Gondi et al., 2021; Murali et al., 2017). Propolis and Terminalia chebula extracts reduce microbial load with minimal tissue irritation (Lee et al., 2017; Tyagi et al., 2013). Clinically, intracanal medicaments containing Triphala, neem, or Morinda citrifolia produce fewer interappointment flare-ups and less postoperative pain compared to calcium hydroxide or formocresol (Kishan et al., 2025; Pathivada et al., 2024). Herbal alternatives offer microbial control, biocompatibility, and regenerative support by disinfecting without cytotoxicity, modulating inflammation, and promoting stem cell repair, making them effective adjuncts in endodontic therapy (Agrawal and Kapoor Agrawal, 2017; Vitali et al., 2022; Anwar et al., 2025; Susila et al., 2023). Table 2 summarises the in vitro and in vivo antimicrobial efficacy, mechanisms of action, and additional biological effects of various herbal irrigants and derivatives compared to conventional endodontic agents against common endodontic pathogens, particularly E. faecalis biofilms.

Table 2

Comparative in vitro and in vivo antimicrobial efficacy of herbal irrigants and derivatives versus conventional endodontic agents.

| Herbal agent | Target/microbial model | Mechanism of action | Efficacy/comparison | Additional effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Triphala (Prabhakar et al., 2010; Shakouie et al., 2014) | Enterococcus faecalisbiofilm (dentin blocks, tooth substrate) | Disrupts bacterial cell wall, chelates metal ions, inhibits enzyme activity | Comparable or superior to 5% NaOCl; similar to 2% CHX in biofilm eradication | Removes organic smear layer; low cytotoxicity; antioxidant and anti-inflammatory |

| Green tea polyphenols (EGCG) (Liao et al., 2020; Ramezanali et al., 2016) | E. faecalis, Fusobacterium nucleatum, mixed root canal flora | Disrupts cell membranes, inhibits virulence enzymes, and reduces biofilm biomass | Significant biofilm reduction; 6% extract comparable to 3% NaOCl | Preserves dentin microhardness; inhibits bacterial adhesion; antioxidant |

| Morinda citrifolia(Divia et al., 2018) | E. faecalis, C. albicans, mixed endodontic flora | Membrane disruption, DNA gyrase inhibition | Similar efficacy to 3–5% NaOCl | Low cytotoxicity; maintains dentin microhardness; supports clinical healing |

| Azadirachta indica(Neem) (Agnihotri et al., 2020; Dutta & Kundabala, 2014) | E. faecalis, S. aureus, C. albicans(biofilm models) | Disrupts microbial adhesion, inhibits virulence | Comparable to CHX and NaOCl; effective against resistant strains | Anti-inflammatory; minimal tissue irritation; reduces postoperative flare-ups |

| Curcumin (Turmeric) (Brar et al., 2019; Dedhia et al., 2018) | E. faecalis, C. albicans(biofilm on tooth substrate) | Inhibits virulence genes, disrupts membranes | Comparable to CHX against E. faecalis; superior to Ca(OH) | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory; enhances healing |

| Propolis (Garg et al., 2014; Tyagi et al., 2013) | E. faecalis, C. albicans(dentin discs) | Biofilm inhibition, antimicrobial activity | Comparable to 5% NaOCl against C. albicans | Biocompatible; promotes tissue repair |

| Nigella sativaoil (Omar et al., 2012) | Mixed anaerobes (pulp infection) | Generates oxidative stress; modulates host immune response | Reduces inflammatory infiltrate; preserves pulp architecture | Immunomodulatory; promotes pulp healing |

| Acemannan (Aloe vera) (Songsiripradubboon et al., 2016) | Pulp tissue (direct pulp capping) | Stimulates odontoblast-like cell proliferation, angiogenesis, and extracellular matrix deposition | Promotes dentin bridge formation; minimal inflammation; favourable clinical outcomes | Regenerative; biocompatible |

| Genipin (Gardenia jasminoides) (Kwon et al., 2015) | Human dental pulp cells | Promotes odontogenic differentiation; upregulates DSPP/DMP-1; scaffold cross-linking | Enhances pulp healing and scaffold stability; not primarily antimicrobial | Supports regenerative procedures |

| Polyherbal combination (Triphala + green tea) (Agnihotri et al., 2020; Garg et al., 2014) | E. faecalisbiofilm, mixed flora | Synergistic disruption of membranes, enzyme inhibition, and anti-adhesion | Greater biofilm inhibition than individual agents; reduces post-procedural flare-ups | Preserves dentin; reduces interappointment pain |

4.2. Evidence for specific herbal agents

4.2.1. Polyphenol-rich extracts

Green tea (Camellia sinensis) extract, particularly EGCG, disrupts E. faecalis biofilms by damaging membranes, inhibiting sortase A and virulence enzymes, and blocking adhesion and quorum-sensing mechanisms (Alaqeel et al., 2023; Chandran et al., 2024; Liao et al., 2020). In vitro studies show that 2–6% green tea extract kills E. faecalis as effectively as 3% sodium hypochlorite in root canals (Ramezanali et al., 2016; Zehra et al., 2025). EGCG also strengthens the antibiofilm properties of dental materials without weakening their mechanical integrity (Liao et al., 2020). Triphala, made from Emblica officinalis, Terminalia chebula, and Terminalia bellirica, kills bacteria by damaging membranes, denaturing proteins, and chelating metal ions needed for microbial metabolism (Alghamdi et al., 2024; Prabhakar et al., 2010). Solutions at 6–10% reduce E. faecalis biofilms by 4–5 log units, matching 5% sodium hypochlorite and sometimes outperforming 2% CHX (Divia et al., 2018; Prabhakar et al., 2010; Shakouie et al., 2014). Triphala removes the organic part of the smear layer while preserving dentin microhardness better than NaOCl (Reshma Raj et al., 2020; Zehra et al., 2025). Clinical studies have shown that it significantly lowers the bacterial load and reduces postoperative symptoms in primary and permanent teeth (Ayub et al., 2025; Divya & Sujatha, 2019; Sharma et al., 2024).

4.2.2. Medicinal Plant Derivatives

Morinda citrifolia contains anthraquinones and scopoletin that break bacterial membranes and inhibit DNA gyrase, killing bacterial cells (Divia et al., 2018; Garg et al., 2014; Nour El Deen et al., 2017). A 6% M. citrifolia juice solution kills bacteria as effectively as 3% NaOCl in primary molars while causing less cytotoxicity (Chandwani et al., 2017; Podar et al., 2015). It also works against C. albicans and mixed endodontic flora (Garg et al., 2014; Tyagi et al., 2013). Nigella sativa oil, containing thymoquinone, induces microbial oxidative stress and lowers host pro-inflammatory cytokines. In primary teeth, it preserves pulp structure with minimal inflammation, matching the effects of formocresol (Agnihotri et al., 2020; Omar et al., 2012; Voina-Țonea et al., 2018). Acemannan, a polysaccharide derived from Aloe vera, exhibits antimicrobial properties and promotes tissue regeneration. Direct pulp capping in primary teeth forms dentin bridges with minimal inflammation and positive clinical outcomes at 3 months (Songsiripradubboon et al., 2016; Kishan et al., 2025). Genipin from Gardenia jasminoides enhances odontoblast differentiation by upregulating DSPP and DMP-1 in dental pulp cells, thereby strengthening scaffolds for stable, biocompatible regeneration (Kwon et al., 2015). Polyherbal combinations enhance antimicrobial activity. Triphala, combined with green tea polyphenols, inhibits biofilms more effectively than individual agents (Alaqeel et al., 2023; Liao et al., 2020; Prabhakar et al., 2010). Neem, turmeric, and propolis show additive effects against resistant E. faecalis and C. albicans (Brar et al., 2019; Garg et al., 2014), acting via membrane disruption, enzyme inhibition, and anti-adhesion, improving outcomes in primary and regenerative endodontic treatments (Agnihotri et al., 2020; Sebatni & Kumar, 2017; Susila et al., 2023).

5. MECHANISMS OF ACTION OF HERBAL AGENTS IN ENDODONTICS

5.1. Disruption of cell walls and membranes

Tannins and gallic acid in Triphala bind to membrane proteins, increase permeability, and cause leakage of intracellular contents, thus leading to lysis (Alghamdi et al., 2024; Prabhakar et al., 2010; Prakash and Shelke, 2014). Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) from green tea enters the lipid bilayers of E. faecalis, disrupts its membrane fluidity, and forms pores that reduce biofilm viability (Alaqeel et al., 2023; Chandran et al., 2024; Liao et al., 2020 ). Azadirachta indica (neem) contains nimbidin and azadirachtin, which destabilise the membranes and block cell wall synthesis (Agnihotri et al., 2020; Dutta & Kundabala, 2014). Morinda citrifolia anthraquinones disrupt the proton motive force and ATP production, thereby causing rapid bacterial death (Divia et al., 2018; Garg et al., 2014). Curcumin from Curcuma longa and thymoquinone from Nigella sativa generate oxidative stress and damage membrane lipids and proteins (Brar et al., 2019; Omar et al., 2012). They lower the risk of bacterial resistance by targeting multiple structural sites (Nour El Deen et al., 2017; Sebatni & Kumar, 2017). These products thus directly rupture the membranes by producing strong antimicrobial effects against endodontic biofilms.

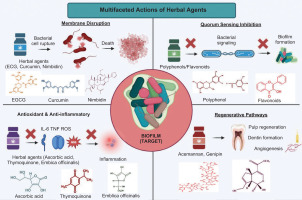

5.2. Enzyme Inhibition and Quorum Sensing Interference

Herbal agents reduce bacterial virulence and disrupt quorum-sensing pathways, thus lowering biofilm formation and persistence. EGCG inhibits sortase A, gelatinase, and other proteases in E. faecalis, impairing adhesion and destabilising the extracellular matrix in biofilms (Alaqeel et al., 2023; Chandran et al., 2024; Liao et al., 2020). Triphala polyphenols suppress the aggregation substance and cytolysin genes, and reduce bacterial coaggregation (Alghamdi et al., 2024; Prabhakar et al., 2010). Propolis and neem extracts inhibit adhesins and fimbrial proteins, thereby preventing bacterial attachment to dentin surfaces (Garg et al., 2014; Tyagi et al., 2013). Many phytochemicals degrade autoinducers or block receptor sites, weakening quorum sensing, reducing biofilm biomass, and increasing bacterial susceptibility to host defences and antimicrobials (Agnihotri et al., 2020; Sebatni & Kumar, 2017). In mixed-species biofilms, green tea and Triphala decrease the production of extracellular polymeric substances (EPSs), thereby weakening the biofilm structure (Chandran et al., 2024; Alghamdi et al., 2024). Combining Triphala with green tea thus enhances biofilm disruption by targeting multiple bacterial pathways simultaneously (Brar et al., 2019; Liao et al., 2020; Prabhakar et al., 2010). Polyphenols and flavonoids suppress bacterial communication, thereby preventing biofilm maturation and enhancing microbial clearance.

5.3. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory pathways

Herbal agents modulate host immune responses and reduce oxidative stress, promoting periapical healing. Emblica officinalis and Terminalia chebula contain ascorbic acid and flavonoids that scavenge reactive oxygen species, protecting pulp and periapical tissues (Alaqeel et al., 2023; Diederich et al., 2023; Shanbhag, 2015). Curcumin and thymoquinone inhibit NF-κB signalling, decreasing pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 in infected pulp tissue (Brar et al., 2019; Omar et al., 2012). Acemannan from Aloe vera promotes odontoblast-like cell proliferation, extracellular matrix deposition, and macrophage polarisation toward an anti-inflammatory phenotype, enhancing angiogenesis during pulp repair (Kishan et al., 2025; Songsiripradubboon et al., 2016). Genipin and ascorbic acid stimulate odontogenic differentiation of dental pulp stem cells by increasing DSPP and DMP-1 expression, supporting dentin regeneration (Alaqeel et al., 2023; Kwon et al., 2015). Clinical and histological studies show that Nigella sativa and acemannan reduce inflammatory infiltrate and preserve organised tissue structure compared to conventional agents (Omar et al., 2012; Songsiripradubboon et al., 2016). Herbal agents combine antimicrobial and host-modulatory actions, making them effective alternatives for endodontic disinfection and regenerative procedures (Agrawal & Kapoor Agrawal, 2017; Ayub et al., 2025). Table 3 provides a detailed overview of the active components, mechanisms of action, additional biological properties, microbial targets, clinical outcomes, and supporting references for a range of herbal agents studied for their efficacy against endodontic pathogens (Figure 2).

Figure 2

. Multifaceted actions of herbal agents against endodontic biofilms.Herbal compounds target biofilms through membrane disruption, quorum-sensing inhibition, antioxidant/anti-inflammatory effects, and stimulation of regenerative pathways, providing a complete approach to overcome antibiotic resistance and promote tissue healing in RCT.

Table 3

Mechanisms of action, biological effects, and clinical evidence of selected herbal agents against endodontic pathogens.

| Herbal agent | Active components | Mechanism of action | Additional properties | Target microbes/models | Outcomes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green tea (Camellia sinensis) | Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), epicatechin, catechins | Disrupts bacterial membrane; inhibits sortase A and proteases (e.g., gelatinase in E. faecalis); interferes with biofilm quorum sensing | Potent antioxidant, anti-inflammatory; chelates smear layer; enhances sealer bond strength; low cytotoxicity; maintains PDL cell viability for 24 h; improves dentin microhardness | E. faecalis, S. mutans, C. albicans, F. nucleatum | Effective against biofilm formation; preserves dentin and PDL cells | Alaqeel et al., 2023; Chandran et al., 2024; Divia et al., 2018; Liao et al., 2020; Hormozi, 2016; Jain et al., 2025; Murali et al., 2017; Salem et al., 2017; Zehra et al., 2025 |

| Triphala (Emblica officinalis, Terminalia chebula, T. bellirica) | Gallic acid, ellagic acid, chebulinic acid, tannins | Chelates Ca2+/Mg2+→disrupts biofilm matrix; generates ROS; denatures microbial proteins | Smear layer removal (pH ~3.5–4.0); antioxidant; promotes dentin conditioning; anti-cariogenic | E. faecalis, S. mutans, C. albicans | Comparable antimicrobial efficacy to 5.25% NaOCl; significantly lower cytotoxicity; reduced postoperative pain | Alghamdi et al., 2024; Ayub et al., 2025; Brar et al., 2019; Divya & Sujatha, 2019; Divia et al., 2018; Prabhakar et al., 2010; Raj et al., 2020; Shakouie et al., 2014; Sharma et al., 2024 |

| Morinda citrifolia(Noni) | Scopoletin, damnacanthal, flavonoids, anthraquinones | Disrupts cytoplasmic membrane; inhibits ATP synthesis; denatures proteins | Mild chelating effect; analgesic; anti-inflammatory; dissolves necrotic tissue | E. faecalis, C. albicans, mixed endodontic flora | Comparable disinfection to NaOCl; minimal tissue irritation; preserves dentin microhardness | Chandwani et al., 2017; Choudhary et al., 2018; Divia et al., 2018; Garg et al., 2014; Gondi et al., 2021; Nour El Deen et al., 2017; Podar et al., 2015 |

| Nigella sativa(Black seed) | Thymoquinone, thymol, nigellone | Generates ROS; inhibits efflux pumps; disrupts membrane potential | Anti-inflammatory; promotes pulpal healing; antioxidant | E. faecalis, S. aureus, Candidaspp. | Preserved pulp vitality; reduced inflammation in primary teeth pulpotomy | Omar et al., 2012; Sinha & Sinha, 2014; Voina-Tonea et al., 2018 |

| Acemannan (Aloe vera) | Acetylated mannose-rich polysaccharides | Modulates macrophages and fibroblasts →enhances TGF-β1, BMP-2; stimulates odontoblast differentiation | Induces reparative dentin bridge; supports pulp regeneration; anti-inflammatory. | Pulp tissue (used as pulp capping agent) | Clinical, radiographic, histologic success; minimal inflammation | Divia et al., 2018; Songsiripradubboon et al., 2016 |

| Azadirachta indica(Neem) | Azadirachtin, nimbidin, catechin, quercetin | Disrupts cell wall synthesis; inhibits adhesion and biofilm formation; alters membrane permeability | Anti-plaque; anti-inflammatory; antioxidant; smear layer removal | E. faecalis, S. mutans, C. albicans | Lower cytotoxicity than CHX; fewer allergic reactions; well-tolerated in pediatric endodontics | Agnihotri et al., 2020; Afshan et al., 2020; Bhargava et al., 2015; Dutta & Kundabala, 2014; Sebatni & Kumar, 2017 |

| Curcuma longa(Turmeric) | Curcumin (diferuloylmethane) | Inserts into membranes →causes leakage; photodynamic activation generates singlet oxygen | Anti-inflammatory; antioxidant; softens gutta-percha in retreatment | E. faecalis, S. aureus, C. albicans | Comparable antimicrobial efficacy to Ca(OH)2; minimal tissue irritation; improves sealer adhesion | Alaqeel et al., 2023; Brar et al., 2019; Jain et al., 2025 |

| Propolis (Bee glue) | Flavonoids (galangin, pinocembrin), phenolic acids, terpenes | Inhibits cell division and protein synthesis; disrupts the membrane; suppresses ATPase | Stimulates collagen synthesis; complex tissue bridge formation; antioxidant | E. faecalis, S. mutans, Candidasp. | Histological evidence of dentin bridge formation; potential root resorption in avulsion storage | Garg et al., 2014; Kwon et al., 2015; Shakouie et al., 2014 |

| Allium sativum(Garlic) | Allicin, ajoene, organosulfur compounds | Inhibits sulfhydryl enzymes →disrupts metabolism; damages membrane | Antioxidant; anti-inflammatory; synergistic with other irrigants | E. faecalis, S. aureus | Lower interappointment flare-up incidence vs. Ca(OH)2; well-tolerated | Alghamdi et al., 2024; Kishan et al., 2025 |

| Myristica fragrans (Nutmeg) | Myristicin, eugenol, terpenes | Disrupts membranes; inhibits biofilm formation | Analgesic (eugenol-like); used in primary tooth pulpotomy | E. faecalis | Success rate comparable to formocresol in primary molar pulpotomy | Mali et al., 2018; Zehra et al., 2025 |

6. CLINICAL OUTCOMES AND SAFETY

6.1. Pulp therapy and regenerative endodontics

Herbal agents demonstrate significant potential in vital pulp therapy and regenerative endodontics by promoting dentinogenesis, enhancing cellular differentiation, and preserving pulp vitality. Acemannan, a polysaccharide extracted from Aloe vera, has been clinically evaluated as a direct pulp capping agent in primary teeth. Songsiripradubboon et al. (2016) conducted a short-term clinical, radiographic, and histologic study and reported that acemannan effectively induced reparative dentin formation and maintained pulp vitality without adverse inflammatory responses. Acemannan not only supports hard tissue bridge formation but also exhibits favourable biocompatibility, which is essential for successful pulp capping outcomes.

Ascorbic acid enhances stem cell activity, supporting regenerative endodontics. Bhandi et al. (2021) demonstrated that it increases the proliferation, differentiation, and secretome activity of SHEDs, stimulating the secretion of growth factors and anti-inflammatory cytokines while promoting osteogenic and dentinogenic pathways (Alaqeel et al., 2023; Kwon et al., 2015). These properties aid pediatric procedures, facilitating apexogenesis and pulp regeneration. Genipin from Gardenia jasminoides promotes odontogenic differentiation in dental pulp cells, increasing alkaline phosphatase activity, mineralised nodule formation, and DSPP and DMP-1 expression, enhancing dentin repair (Kwon et al., 2015). Herbal agents also protect pulp tissue through antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory effects. Polyphenols, flavonoids, and other bioactive compounds reduce oxidative stress and inflammation, supporting stem cell activity and reparative dentin formation (Alghamdi et al., 2024; Diederich et al., 2023; Omar et al., 2012; Shanbhag, 2015).

6.2. Patient acceptance

Herbal irrigants demonstrate superior safety and tissue compatibility compared to synthetic agents, such as NaOCl and CHX. Venkateshbabu et al. (2016) and Sivakumar et al. (2018) reported that NaOCl effectively kills E. faecalis and other pathogens but may cause cytotoxicity, tissue irritation, and severe complications if extruded beyond the apex. CHX is considered less toxic; however, Venkateshbabu et al. (2016) suggested that it can still cause tooth staining, mucosal irritation, and allergic reactions. Herbal irrigants such as Azadirachta indica (neem), Triphala, and green tea polyphenols exhibit minimal cytotoxicity and low adverse effects. Shanbhag (2015) and Alaqeel et al. (2023) indicated that neem, turmeric, and Triphala maintain periapical tissue health and rarely trigger inflammation or allergies. Their polyphenols and flavonoids provide antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and membrane-stabilising benefits. Clinical studies support these findings: Triphala, neem, and a 2% CHX gel exhibited similar antimicrobial activity against E. faecalis, while the herbal groups experienced fewer postoperative symptoms, as reported by Sharma et al. (2024) and Garg et al. (2014), respectively. Garlic and Triphala were found to reduce interappointment flare-ups compared to calcium hydroxide, reflecting improved tissue tolerance and immune support, as suggested by Kishan et al. (2025) and Garg et al. (2014), respectively. Herbal compounds act by disrupting microbial membranes, inhibiting enzymes, and interfering with biofilm formation, thereby limiting bacterial resistance and supporting safe, sustainable clinical use, as highlighted by Sebatni & Kumar (2017) and Anwar et al. (2025), respectively. Herbal agents offer antimicrobial efficacy, promote tissue regeneration, and demonstrate favourable safety profiles, making them relevant alternatives in modern endodontics. Compounds such as acemannan, ascorbic acid, and genipin support dentinogenesis and pulp repair (Diederich et al., 2023; Kwon et al., 2015; Songsiripradubboon et al., 2016 ). Triphala, neem, and green tea ensure effective disinfection while causing minimal tissue irritation (Garg et al., 2014; Shanbhag, 2015). Acting as both antimicrobial and host-modulatory agents, they reduce postoperative inflammation and enhance regenerative outcomes, especially in pediatric or sensitive patients (Diederich et al., 2023; Omar et al., 2012; Songsiripradubboon et al., 2016). Standardised formulations, dose optimisation, and large-scale clinical trials are required to validate widespread adoption, yet current evidence supports herbal agents as biologically active, safe, and effective options in endodontic therapy.

6.3. Limitations and future perspectives

Herbal agents in endodontics show considerable promise, but several limitations hinder their widespread clinical adoption. Variability in plant origin, harvesting conditions, and extraction methods can lead to inconsistent concentrations of active compounds, directly affecting the antimicrobial efficacy and reproducibility of results (Brar et al., 2019; Divia et al., 2018; Liao et al., 2020; Prabhakar et al., 2010). Differences in solvent systems, processing techniques, and storage conditions further compound this variability, making inter-study comparisons difficult. Alaqeel et al. (2023), Divia et al. (2018), and Songsiripradubboon et al. (2016) stated that most evidence on herbal endodontic agents derives from in vitro studies or small-scale clinical trials, which limits the strength and generalisability of the findings. Brar et al. (2019) reported that few large, randomised controlled trials exist, which restricts the evaluation of efficacy, safety, and long-term outcomes. Agnihotri et al. (2020) and Dutta & Kundabala (2014) highlighted that regulatory standards for herbal dental therapeutics remain limited, complicating quality control, approval, and clinical standardisation. Divia et al. (2018) and Garg et al. (2014) proposed that future research should focus on nanoformulations and controlled-release delivery systems to enhance tissue penetration, antimicrobial activity, and sustained effects. Prabhakar et al. (2010) and Chandran et al. (2024) suggested integrating ethnopharmacological knowledge with modern endodontic protocols to select herbal agents based on traditional use while validating their effects scientifically. Brar et al. (2019) and Liao et al. (2020) further proposed investigating synergistic combinations, such as EGCG with EDTA or Triphala with green tea polyphenols, to improve biofilm removal and target multiple bacterial pathways. Standardising extraction methods, concentrations, and trial designs is essential to establish herbal agents as safe and effective in endodontics.

6.4. Comparative cost-effectiveness and accessibility in low-resource settings

Herbal alternatives in endodontics offer practical, economic, and biological advantages, especially in low- and middle-income regions where conventional materials are limited. They are inexpensive, readily available, stable during storage, and require minimal infrastructure for use (Anwar et al., 2025; Ferrazzano et al., 2011). Tewari et al. (2016) emphasised that such plant-based medicines align with WHO recommendations for primary healthcare, promoting affordable and accessible treatment. In contrast, conventional agents like NaOCl, CHX, and MTA are costly, require controlled storage, and may degrade in hot, humid environments (Ferrazzano et al., 2011; Taheri et al., 2011). Herbal agents, including Triphala, neem, green tea, and Morinda citrifolia, can be prepared locally through simple aqueous or ethanolic extractions, reducing procurement and operational costs (Chandwani et al., 2017; Prabhakar et al., 2010). Triphala, a mixture of Emblica officinalis, Terminalia chebula, and T. bellirica, is widely cultivated in South Asia and available as an inexpensive powder (Brar et al., 2019; Prakash & Shelke, 2014). Neem leaves are abundant in rural areas and produce effective extracts against E. faecalis and C. albicans (Dutta & Kundabala, 2014; Nayak et al., 2012). Cost comparisons indicate that treatments with 5% NaOCl or 2% CHX are three to five times higher than protocols using Triphala or green tea extract (Ferrazzano et al., 2011; Sinha & Sinha, 2014). In pediatric cases, where multiple visits are required, herbal capping agents such as Nigella sativa oil or acemannan provide comparable outcomes at a cost of under USD $3 per tooth, compared to USD $20–30 for formocresol or MTA (Diederich et al., 2023; Omar et al., 2012).

Herbal powders store longer than NaOCl, which loses potency quickly (Ferrazzano et al., 2011; Velmurugan et al., 2013). Stable powders reduce restocking needs, minimise treatment interruptions, and allow auxiliary health workers to deliver care in underserved regions.

School-based programs in India have used Terminalia chebula mouthrinses to lower Streptococcus mutans counts with minimal training (Nayak et al., 2012; Palit et al., 2016). Coconut water and green tea extract serve as low-cost, effective storage media for avulsed teeth when HBSS is unavailable (Carounanidy et al., 2007; Ferrazzano et al., 2011). Variability in plant sources, extraction methods, and active compound concentrations limits reproducibility (Agnihotri et al., 2020). Initiatives such as the Indian Herbal Pharmacopoeia and WHO safety guidelines offer frameworks for quality control that can be adapted locally (Ferrazzano et al., 2011; Tewari et al., 2016). Standardised, locally validated herbal kits could expand access to safe, affordable root canal therapy, reduce reliance on imported chemicals, and ensure consistent efficacy in low-resource settings (Sinha & Sinha, 2014).

7. CONCLUSION

Herbal agents offer a practical and biologically grounded approach for endodontic therapy. They combine antimicrobial and regenerative effects, eliminating pathogens while promoting pulp and periapical healing. Compounds such as acemannan, ascorbic acid, and genipin stimulate odontoblast differentiation, promote the formation of reparative dentin, and regulate immune responses. Clinically, herbal irrigants and medicaments show high tolerability, minimal cytotoxicity, and reduced postoperative discomfort, which benefits pediatric and sensitive patients. Endodontic practice in today’s era still depends on synthetic irrigants and medicaments, which provide strong antimicrobial effects but often have detrimental effects on the tissues. Herbal preparations address these limitations by offering safer options that also enhance tissue repair and regeneration. Their antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and regenerative actions align with biologically directed treatment strategies. Standardisation of plant sources, extraction methods, and concentrations is essential for consistent outcomes. Clinical trials are required to determine optimal dosage, treatment protocols, and long-term safety. Future work includes the development of nanoformulations for controlled release, evaluation of synergistic combinations with conventional agents, and incorporation of traditional pharmacology into evidence-based endodontic practice.